Résumés

Summary

Restrictions implemented around the world to contain the spread of COVID-19 have had various consequences for workers. Emotional distress, maladaptive behaviours, and issues such as sleep disorders, irritability, and loss of motivation are expected, particularly among employees not used to telework. We wished to find out whether previous telework experience helped workers maintain their quality of life during the lockdown. Data were collected through an anonymous online survey of adult workers ≥ 18 years old in Canada, between May 25, 2020, and June 26, 2020. The survey was completed by 604 teleworkers, 66.8% of whom had not teleworked before the lockdown. The respondents provided self-reported data on sociodemographics, mental health issues, and quality of life. We assessed changes in quality of life by using paired t-tests and linear regression to identify significant determinants. Our analysis shows a decline during the lockdown in all quality of life indicators: stress, irritability, sleep quality, motivation, ability to undertake projects, and surfing the Internet without a specific goal (p < 0.001). The decline was mainly driven not by lack of previous telework experience but rather by a combination of three factors: having young children at home, having a high frequency of telework, and being a man.

Abstract

COVID-19 lockdowns have significantly impacted workers over the last year. In particular, telework has significantly changed the way work is done. We wished to find out whether previous telework experience helped workers maintain their quality of life during the lockdowns. By analyzing data collected from Canadian workers in the spring of 2020, we found that quality of life indicators significantly declined during the lockdown, and that previous telework experience did little to protect workers. We conclude that quality of life declined the most among teleworkers who had young children at home during the lockdown and who also had a high frequency of telework. This combination seems to have been more detrimental to men than to women.

Keywords:

- COVID-19,

- lockdown,

- telework,

- quality of life,

- remote work

Résumé

Les restrictions mises en place dans le monde entier pour contenir la propagation du virus de la COVID-19 ont eu diverses conséquences sur les travailleurs. Il peut en découler une détresse émotionnelle, des comportements inadaptés et des problèmes tels que des troubles du sommeil, de l'irritabilité et une perte de motivation, en particulier chez les employés qui n'ont pas l'habitude de télétravailler. Cette étude vise à déterminer si l'expérience du télétravail peut protéger les travailleurs contre les changements dans leur qualité de vie pendant les confinements liés à la COVID-19. Pour étudier ce phénomène, des données ont été recueillies par le biais d'une enquête en ligne anonyme menée auprès de travailleurs adultes âgés ≥ 18 ans au Canada, entre le 25 mai 2020 et le 26 juin 2020. L'enquête a été complétée par 604 télétravailleurs, dont 66,8 % n'étaient pas habitués au télétravail avant les confinements. Les informations recueillies concernent des données sociodémographiques, des problèmes de santé mentale et la qualité de vie. Les changements dans la qualité de vie ont été évalués à l'aide de tests-t appariés et de régression linéaire afin d'identifier les déterminants significatifs. L'analyse révèle que tous les indicateurs de qualité de vie [stress, irritabilité, qualité du sommeil, motivation, capacité à entreprendre des projets et navigation sur Internet sans but précis (p < 0,001)] se sont détériorés pendant les confinements. Le facteur le plus déterminant de cette détérioration n'est pas l'expérience préalable du télétravail, mais plutôt la présence de jeunes enfants à la maison couplée à la fréquence du télétravail et le sexe des répondants.

Mots-clefs:

- COVID-19,

- Confinement,

- Télétravail,

- Qualité de vie,

- Travail à distance

Corps de l’article

Introduction

The lockdowns enforced in many countries in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the immediate post-lockdown periods, have been associated with major personal lifestyle changes and probable psychological effects. During the lockdowns, more than 3.4 billion people in 84 countries were forced to follow stay-at-home orders (Bouziri, Smith, Descatha, Dab, & Jean, 2020). In Quebec, Canada, an enforced lockdown started on March 23, 2020 and ended on May 11, 2020. It impacted a significant number of employees in the public and private sectors, affecting all economic activities deemed non-essential. For instance, the government closed stores (clothing, sports, etc.), restaurants, bars, cafés, theatres, museums, ski resorts, national parks, and construction sites. Gatherings and visits at nursing homes were also prohibited at all times. Travel between different regions or different cities was prohibited, and police checkpoints were in place to restrict access to certain regions. Unlike the situation in other countries, Quebec’s lockdown did not include a ban on going outside or time limits on outdoor physical activity. There was no certificate system for travelling as there was during the lockdown in France. There were also changes in the place of work: in June 2020, 73% of Quebec companies had over 50% of their employees working remotely, and 30% had 100% of their employees doing so (CRHA, 2020).

The sudden changes in work arrangement necessarily raise questions about the consequences of the pandemic for work life. Although the literature highlights the advantages of remote activities for organizations and employees (Pitafi, Rasheed, Kanwal, & Ren, 2020), the situation experienced during the lockdown was unique. Even if some commonly recognized benefits of telework cannot be denied—such as less stress from not having to commute every day, a more comfortable work environment, and more work autonomy—these benefits can be offset by such costs as increased feelings of self-isolation, anxiety, and various addictions (to drugs, videos, food, etc.) (Hsieh, Tsai, & Hsia, 2020). By investigating this phenomenon in the exceptional context of the COVID-19 pandemic, it may be possible to contribute meaningful knowledge to the scientific literature, since telework has seldom been studied under such conditions. Habits have been disrupted by the specific conditions of the pandemic, with its severe limitations on one’s mobility and degree of social interaction (with co-workers, family members, and friends). One’s state of mind has similarly been impacted by unplanned telework from home with family members who require various levels of attention, by fears about the future (unemployment, lower income), and by the government’s lack of options for managing the pandemic (Hallin, 2020).

There have been a significant number of reports of unexpected lockdown-related psychological effects, including anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, symptoms of dependency (tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, drugs), irritability, and aggressiveness (Brooks et al., 2020), which may impact the mindset and self-esteem of teleworkers (Brem, Viardot, & Nylund, 2021). Another source of fear, confusion, and anger has been the stigma of quarantine for anyone who contracted the virus or who came into contact with someone who tested positive (Hamouche, 2020). Data from the COVID-19 lockdown also indicate changes in daily routines, as well as personal and/or group initiatives to overcome lockdown-related social isolation, i.e., increased Internet use (movies, TV shows, pornography, online gaming); new practices (online happy hours); and telework (Gjoneska et al., 2022). During this period, the Internet and social media broadly helped reduce feelings of isolation and helped people stay in touch with family, friends, and co-workers while massively transforming their work practices and their collaboration and connectivity with others (Prodanova & Kocarev, 2021).

Businesses imposed telework to comply with lockdown recommendations and directives issued by the government and public health departments. They viewed telework as a quick and efficient solution with low implementation costs (Belzunegui-Eraso & Erro-Garcés, 2020). Although it already existed as a practice, telework became even more widespread during the lockdowns. In a recent study, most Canadian companies (72%) reported that nearly 50% of their employees work remotely, while nearly 30% reported that all of their employees telework full-time (CRHA, 2020).

Teleworkers may have experienced a resulting lack of real social interaction, along with anxiety due to the pandemic. Through this research, we have investigated the impact of telework due to an enforced lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic and the related psychological and professional consequences. Special attention has been paid to differences in stress, well-being, and quality of life between people used to this work arrangement and those not used to it. Such investigations contribute to knowledge and understanding of telework issues during a crisis as exceptional as the COVID-19 pandemic, thus providing a new perspective on such issues.

Theoretical Background

Most of the available research on telework was conducted before the COVID-19 crisis. Our research builds on this previous work by filling a gap in the literature and by describing the issues that emerge from a pandemic. A review of the literature shows three main determinants of the decision to telework: 1) type of work; 2) personal characteristics (level of education, income, family situation, number of children); and 3) worker mobility. The type of work, as defined for instance by job position or industry, also impacts the ability to work remotely (He & Hu, 2015). Thus, office workers are more inclined to work from home. This inclination has grown with the spread of information technologies, the increase in worker mobility, and the worsening of commuting issues (Frey & Osborne, 2017; Haddad, Lyons, & Chatterjee, 2009). Similarly, personal characteristics seem to play a role. Workers with high incomes (He & Hu, 2015; Sener & Reeder, 2012) and high levels of education are more likely to work from home (de Graaff & Rietveld, 2004; Singh, Paleti, Jenkins, & Bhat, 2013). Research findings are inconsistent regarding perspectives of telework. Some studies have shown that telework is more convenient for people without children (Peters, Tijdens, & Wetzels, 2004), and others that the presence of young children encourages telework (Iscan & Naktiyok, 2005) and is particularly appreciated by women with children (Mokhtarian, Bagley, & Salomon, 1998). Lastly, higher mobility also explains the decision to telework, as time spent commuting is a positive factor in the adoption of telework (Nurul Habib, Sasic, & Zaman, 2012).

Employers typically concede a high level of autonomy to those teleworkers, who have complex and multifaceted lifestyles. Previous studies have identified circumscribed benefits of telework for organizations and employees (Pitafi et al., 2020). Teleworkers feel empowered in their daily tasks, although their high level of autonomy and their ability to organize their work as they wish can make them feel indebted to their employer and think they have to prove that they deserve this favour (Nakrošienė, Bučiūnienė, & Goštautaitė, 2019). Our literature review also revealed certain disadvantages of telework. Some employees have a high level of anxiety and compulsive behavior, which is due to a perceived moral obligation to stay connected and responsive and which has been exacerbated by new technologies (Elhai, Levine, Dvorak, & Hall, 2016). In such cases, they may compulsively and excessively check devices and any tools connecting them to the organization, thus adversely affecting their quality of life and work performance.

During a lockdown, telework is no longer a deliberate personal choice but rather an organizational and national obligation. Anticipated benefits are likely to coincide with resource access problems and increasing demands. Especially relevant in this context is the job demands-resources model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Access to additional resources is needed to deal with increasing demands (e.g. isolation, stress, work/family balance) and declining quality of daily life. Therefore, previous telework experience may alleviate negative impacts, as was confirmed when telework was introduced suddenly during the pandemic. It should be noted that the intensity of telework during the pandemic (e.g., increase in emails and online meetings), combined with the family context (especially the presence of young children), did impact work performance (Adisa, Aiyenitaju, & Adekoya, 2021).

Consequences of Telework during a Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic forced many workers to adopt new ways of organizing work due to self-isolation and telework. Despite research interest in the effects of telework, few studies have focused on its impact during the period. The unprecedented nature and scope of the crisis has opened up prospects for research that might fill this gap in the literature (Nielsen, Christensen, & Knardahl, 2021). Constraints imposed by the lockdowns have had psychological, physiological, and/or psychosocial consequences for workers, such as loss of sleep, feelings of isolation, anxiety, stress, intention to quit, and loss of motivation (Durieux, 2020). Studies during the pandemic revealed a higher level of stress due to the ongoing nature of telework (Hallin, 2020; Jaiswal & Arun, 2020). Other studies during the pandemic also showed that well-being decreased and stress increased in people working from home. Job satisfaction research produced conflicting results: in one study, 65.9% of the respondents were satisfied with the increase in telework during the pandemic (Baert, Lippens, Moens, Weytjens, & Sterkens, 2020), while other studies suggested the opposite and reported feelings of isolation, stress, and anxiety (Nielsen et al., 2021; Rubin, Nikolaeva, Nello-Deakin, & te Brömmelstroet, 2020). Increase in job satisfaction depends on the ability to work remotely, the quality of employer support, and an adequate work-family balance. Hence, dissatisfaction with telework during a pandemic may result from a significant drop in face-to-face social contact. Motivation can also be affected (Hallin, 2020). Some people may have a negative experience during lockdowns, when telework is not a deliberate and voluntary choice, as it is at other times (Hallin, 2020). Among people working from home during the pandemic, more than 25% believed that telework decreased their chances of promotion and hindered their career development, thus reducing their ability to project themselves into the future (Baert, Lippens, Moens, Sterkens, & Weytjens, 2020). More than half of teleworkers also mentioned that telework had a negative effect on relationships with their co-workers and that the feeling of closeness to their employer had decreased (Baert, Lippens, Moens, Weytjens, et al., 2020). The latter effect may weaken one’s organizational commitment. Teleworker productivity was also lower during the lockdown because of a lower-than-usual ability to concentrate and a significant increase in connection time (Hallin, 2020). This situation was particularly true when workers were not given enough resources; they tended to perceive job tasks as more demanding and felt more negatively about working from home (Nauman, Raja, Haq, & Bilal, 2019).

Previous Telework Experience

Various studies of worker attitudes and behaviours have shown the impact of previous telework experience on worker commitment to adoption of telework (Martínez‐Sánchez, Pérez‐Pérez, De‐Luis‐Carnicer, & Vela‐Jiménez, 2007; Pérez, Sánchez, de Luis Carnicer, & Jiménez, 2004). These findings are consistent with those of Illegems and Verbeke (2004), who showed that managers who had not themselves undertaken telework were less likely to adopt it. Such managers perceived negative consequences: increased social isolation, decreased ability to work in a team, and reduced performance. These consequences were not perceived by managers who had previously adopted telework. Commitment to telework increased with previous telework experience and acculturation. Thus, workers accustomed to telework tend to have a higher level of commitment to it than do others. A recent study suggests that previous experience with telework determined the degree to which workers appreciated it and had difficulties with it during the pandemic (Rubin et al., 2020). The study also found significant differences between the responses of people who teleworked regularly before the pandemic (at least once a week) and the responses of those who did not telework at all or did so rarely (less than once a week). In fact, 30% of people who were not used to telework now perceived face-to-face contact with their co-workers as less important than before, whereas only 16% of workers accustomed to telework had that perception (Rubin et al., 2020). However, these findings contradict those of another study: respondents who had no experience with telework before the pandemic reported negative effects from telework, such as lack of interaction with the manager, lack of feedback and guidance, difficulties accessing information, lack of inspirational work atmosphere, manager’s inability to estimate the workload, and many doubts about performance evaluation (Raišienė, Rapuano, Varkulevičiūtė, & Stachová, 2020). Those findings are consistent with a previous research finding: reduced interactions due to telework tend to lead to social isolation. For a category of workers, the autonomy generated by remote work increased the feeling of being isolated from managers and colleagues. The resulting loss of empowerment in their work reduced their effectiveness (Park & Cho, 2020; Silva-C, 2019). Thus, if people have no previous experience with telework, they may experience it more negatively than those who do. The above findings lead to the following hypothesis:

H1: Previous experience with telework is positively related to the quality of life of teleworkers during a lockdown.

Frequency of Telework

Telework frequency is the time one spends doing remote work: from occasional or recurring to continual (Wiesenfeld, Raghuram, & Garud, 1999). Various studies have shown that it significantly affects not only employee satisfaction but also feelings of isolation and organizational attachment (Bailey & Kurland, 2002; Thatcher & Zhu, 2006). Indeed, it tends to have psychological effects on social interactions. The more frequently one does telework, the less satisfied one will be (Halford, 2005; Peters et al., 2004). This is particularly true when one cannot establish new daily routines with coworkers or maintain relationships with non-teleworkers in the organization. For Bélanger (1999) and Harris (2003), the higher the telework frequency, the less one will feel committed to the organization. Recent studies suggest that telework frequency may affect quality of life (Even, 2020; Golden & Eddleston, 2020). Indeed, the negative impacts of isolation are more significant when the time spent teleworking is high (Golden, Veiga, & Dino, 2008). Even (2020) corroborates this finding in a pandemic context: when people work remotely more than twice a week, they perceive more organizational isolation. Golden and Eddleston (2020) also demonstrate that telework frequency is negatively correlated with career success (e.g., promotions, compensation), thus confirming that teleworkers feel “invisible to the company” (Taskin & Bridoux, 2010). Telework frequency is also believed to be responsible for loss of organizational identity and commitment. This would imply a negative relationship between telework frequency and sense of belonging to the company (Harris, 2003; Vayre, 2019). Perception of telework during a lockdown would therefore become more negative as telework becomes more frequent, the result being less motivation and satisfaction and a diminished quality of life (Bailey & Kurland, 2002; Raišienė et al., 2020; Thatcher & Zhu, 2006). By decreasing the frequency of telework, employers would reap its benefits while reducing its disadvantages. The above findings lead to the following hypothesis:

H2: Frequency of telework is negatively related to the quality of life of teleworkers during a lockdown.

Effect of Young Children at Home

Work-life balance appears to be key to achieving a high quality of life during telework and thus increasing worker satisfaction and performance (Baines & Gelder, 2003). The work environment at home tends to increase or decrease the perceived benefits of telework (Durieux, 2020). Indeed, because a lockdown exacerbates the multi-use aspect of the home, there may be sources of distraction that would be absent in normal times (Hallin, 2020). When a lockdown makes it necessary to work at home with the family, there seem to be none of the main reported advantages of telework (e.g., higher concentration, higher productivity, higher quality of work) (Vayre, 2019). Hallin (2020) mentions that high productivity from telework is often related to a peaceful work environment free from distraction, but this is not necessarily the case during a lockdown if teleworkers are at home with other family members or with young children. It has also been shown that the presence of children considerably increases the stress of telework (Rubin et al., 2020). The workday is characterized by unusual workloads, supervision of children’s schoolwork, and other family roles of parents at home during the pandemic (Al-Balushi et al., 2014), the result being frequent conflicts within families (Adisa et al., 2021). Because young children require a high level of attention, it is often difficult for parents to strike a balance between their personal and working lives. Such teleworkers reported feeling less satisfied because of their long working days, their lack of support and resources, and, in particular, the unforeseen issues that they (mainly women) had to deal with (Adisa et al., 2021). Overall, when young children stay at home during a pandemic, the negative effects of telework seem to be increased and the positive effects decreased (Baert, Lippens, Moens, Weytjens, et al., 2020). The above findings lead to the following hypotheses:

H3: The presence of young children negatively affects the relationship between telework and quality of life specifically, the greater the number of young children, the less positive this relationship will be.

H4: The presence of young children negatively affects the relationship between telework frequency and quality of life. The greater the number of young children, the less positive this relationship will be.

Effect of Gender

In recent decades, there has been a decrease in the time women spend on household chores, even though they still do more of the housework (Bianchi, Sayer, Milkie, & Robinson, 2012). Women have been conditioned to accept certain responsibilities outside their work, from which men are exempt. Women are considered to be the family caregivers; they are therefore associated with the family, believed to be more involved with the family, and identified with the family role. Consequently, by assuming family and household responsibilities and negotiating accommodations within the family circle, women perform roles that may influence work-family balance in the context of telework (Vayre, 2019). The effects of telework on the quality of life of teleworkers could be decreased by certain factors, including gender, parental status, and conflicting demands between work and family life (Lister & Harnish, 2019; Song & Gao, 2020). It has also been argued that the effect of telework on subjective well-being varies by gender. Indeed, the subjective well-being of women who work remotely and have children is more likely than that of men to be negatively affected (Song & Gao, 2020). One reason given here is that women, when teleworking, are more likely to have to look after children and do household chores, both of which interfere with their work (Song & Gao, 2020). Their career development is also reported to be negatively affected (Maruyama & Tietze, 2012). Hamouche (2020) points out that women have a greater psychological vulnerability to stress than men, which could explain why, during the pandemic, they were more adversely affected (Hamouche, 2020). Men feel less sad and tired when doing telework on weekdays and consider it more meaningful on weekends/holidays, while women feel less happy and more stressed (Song & Gao, 2020). The above findings lead to the following hypotheses:

H5: Being a woman negatively affects the relationship between previous telework experience and quality of life. The relationship is thus more negative for women than for men.

H6: Being a woman negatively affects the relationship between telework frequency and quality of life. The relationship is thus more negative for women than for men.

H7: Being a woman negatively affects the relationship between presence of young children and quality of life. The relationship is thus more negative for women than for men.

Method

To test our research hypotheses, we designed an online self-administered questionnaire. We collected data anonymously from French Canadian respondents through social networks between May 25 and June 26, 2020. The survey was designed using the Qualtrics© software and conducted on a French Canadian population after a pre-test on a sample of respondents in France. To ensure maximum response, the survey was designed to take roughly 10 minutes to complete. The sample consisted of people who continued to work either full-time or part-time by teleworking during the lockdown (n = 604 teleworkers out of 1160 respondents in total). Respondents were recruited by the snowball method, a non-probabilistic sampling technique.

Measurement Tools

The measurement scales were a combination of validated items. The dependent variables included stress, irritability, sleep quality, capacity to undertake projects and project oneself into the future, general motivation, and desire to surf the Internet without a specific goal. All the dependent variables were measured on a Likert scale (from 0 to 10). The scales came from research in psychology, mainly CES-D tools for measuring the level of depression in a population (Andresen et al., 1993;(Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994; Lenzo, Quattropani, Sardella, Martino, & Bonanno, 2021; Radloff, 1977). Respondents had to answer respond to the same items twice: the first time for their behavioural state before the lockdown and the second time for their behavioural state during the lockdown. We thus divided them into two groups: those who had never or only seldom teleworked (never or once every two weeks) and those who were used to telework (once or more per week) (Rubin et al., 2020). For age, there were 9 categories ranging from under 18 to 85 or over. For gender, there were two categories (1 = men; 2 = women). The respondents were also divided into those with young children under 12 years old (= 2) and those without young children (= 1). Finally, they were divided into those who teleworked part-time (= 1) while continuing to do some activities at the office and those who had switched to telework full-time (= 2).

To minimize bias and misunderstanding, the questionnaire was pre-tested in France on a sample of 40 respondents. As this research was based on a multicultural approach, the Canadian questionnaire was adapted for the North American context.

Statistical Analysis

The data analyses were all performed using SPSS® Statistics 26 (IBM). Demographic characteristics were reported using descriptive statistics. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. A descriptive analysis of sociodemographic and telework variables was performed. A paired sample t-test was used to estimate differences between the pre-lockdown period and the lockdown period. Regression analyses were then performed to determine how previous telework experience and telework frequency during the lockdown interacted with various dependent variables. Finally, moderated multiple regression was used to determine how previous telework experience and telework frequency during the lockdown interacted with gender and presence of young children. Age and gender were entered at Step 1 as control variables. Our main predictors (previous telework experience and telework frequency, all of which were centred; see Aiken and West, 1991) were entered at Step 2. Finally, the product terms of interest to our study, calculated from the centred predictors, were entered at Step 3.

Results

The population was composed of people who continued to work during the lockdown by teleworking either full-time or part-time. Table 1 shows that women were overrepresented (75.6%) and that more than 50% of the respondents were between 35 and 54 years old. The majority had a partner, with 38.7% having a common-law spouse and 35.8% being married. Nearly 40% of the respondents were locked down at home with children under 12 years old. Finally, a majority (66.1%) had no previous telework experience before the lockdown, and a majority (78.5%) were transferred to full-time telework.

Table 1

Sociodemographic and Telework Profile of Respondents

All variables measured during the lockdowns, as shown in Table 2, indicate that the respondents perceived the change negatively. There were increases in stress (5.75 vs 6.70; p < 0.001), irritability (4.93 vs 5.83; p < 0.001), and desire to surf the Internet aimlessly (2.61 vs 3.65; p < 0.001) and decreases in motivation (7.72 vs 6.33; p < 0.001), sleep quality (7.54 vs 6.68; p < 0.001), and ability to undertake projects and project oneself into the future (8.09 vs 6.12; p < 0.001).

Table 2

Quality of Life Before and During Lockdown

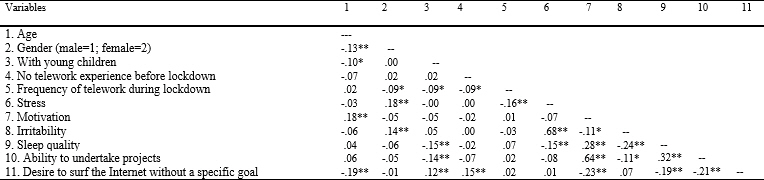

Table 3 shows the correlation matrix. Among other things, a positive relationship can be seen between gender and stress (r = 18; p <= .01), and between gender and irritability (r = 14; p <= .01). It seems that women’s health declined more during the lockdown than did men’s health. Presence of young children also seems to have led to a decline in quality of life during the lockdown in terms of sleep quality (r = -.15; p <= .01) and ability to undertake projects (r = -.14; p <= .01). This situation also increased the desire to surf the Internet without a specific goal (r = .12; p <= .01). Lack of previous telework experience was positively related to surfing the Internet without a specific goal (r = 15; p <= .01), and telework frequency was negatively related to stress (r = -.16; p <= .01). Interestingly, the increase in stress during the lockdown was associated with an increase in irritability (r = .68; p <= .01) and a decrease in sleep quality (r = -15; p <= .01). Respondents who stayed motivated during the lockdown continued to sleep well (r = .28; p <= .01) and were still able to undertake projects (r = .64; p < =.01). Sleep quality also seemed to be related to lower irritability (r = -.24; p <= .01), greater ability to undertake projects (r = .32; p <= .01), and less inclination to surf the Internet without a specific goal (r = -19; p <= .01).

Table 3

Correlation Matrix

The results in Table 4 suggest that previous telework experience and telework frequency may not explain much of the variation in teleworker behaviours and attitudes during a lockdown. When controlling for age, gender, and presence of young children, previous telework experience affected only the desire to surf the Internet without a specific goal (β = 0.10; p <= 0.05), while telework frequency appeared to be associated with less stress (β = -0.08; p <= 0.05). These results do not truly support Hypotheses 1 and 2. Age was associated positively with motivation (β = 0.13; p <= 0.05) and negatively with surfing the Internet without a specific goal (β = -0.11; p <= 0.05), while women seem to have developed more stress and irritability than did men during the lockdown (β = 0.07; p <= 0.05; β = 0.08; p <= 0.05). It is also interesting to note that being around young children during the lockdown was negatively related to sleep quality (β = -0.10; p <= 0.05) and ability to undertake projects (β = -0.09; p <= 0.05) and positively related to desire to surf the Internet without a specific goal (β =0.11; p <= 0.05).

Table 4

Regression Analyses between Sociodemographic and Telework Profile Variables, for Quality of Life Indicators

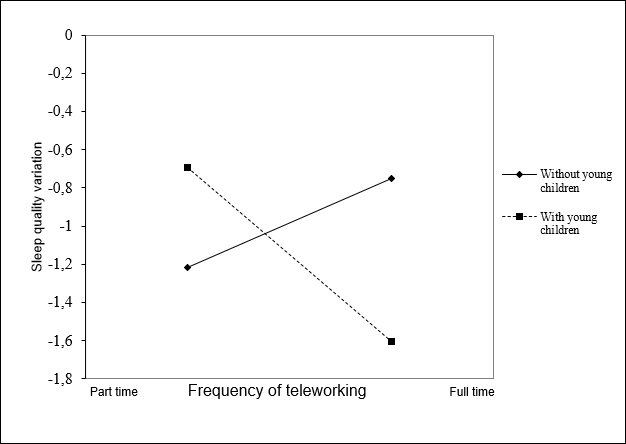

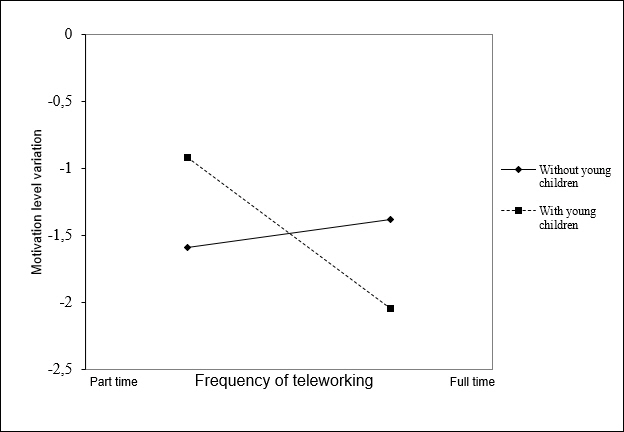

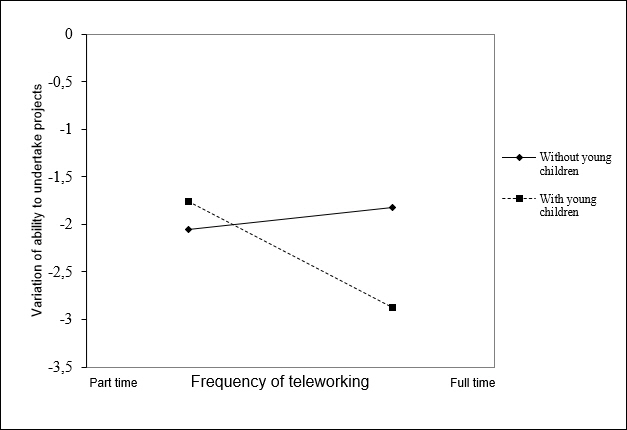

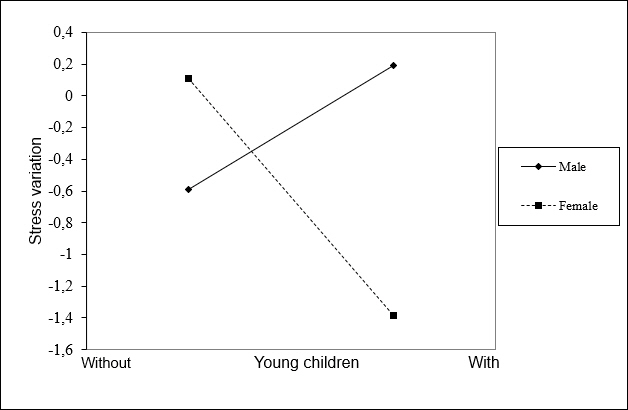

Contrary to Hypothesis 3, the presence of young children during a lockdown did not significantly affect the relationship between previous telework experience and quality of life. However, the presence of young children during a lockdown did strengthen the relationship between telework frequency and decline in quality of life. When the presence of young children was combined with higher telework frequency, there was less motivation (β = -0.08; p <= 0.05), lower sleep quality (β = -0.09; p <= 0.05), and less ability to undertake projects (β = -0.08; p <= 0.05) than before the lockdown. The results partially support Hypothesis 4. To illustrate and better understand these interactions, a linear regression was plotted for sleep quality, motivation, and ability to undertake projects as a function of telework frequency, at 1 SD below and 1 SD above the mean of presence of young children during the lockdown (Aiken, West, & Reno, 1991). These relationships appear in Figures 1 to 3. When sleep quality was plotted as a function of telework frequency, the relationship was significantly positive without young children [t (551) = 2.316, p < 0.05] and significantly negative with young children [(t (551) = -1.985, p < 0.05]. Presence of young children seems to affect the relationship between telework frequency and sleep quality (Figure 1). The relationship of telework frequency with motivation was non-significant without young children [t (551) = 0.848, N.S.] and significantly negative with young children [t (6=551) = -1.964, p < 0.05] (Figure 2). The relationship with ability to undertake projects was positive but non-significant without young children [t (551) = 0.890, N.S.] and significantly negative with young children [t (551) = -1.945, p < 0.05]. It seems that teleworking full-time with young children reduces the ability to project oneself into the future and undertake projects (Figure 3). When we examined the effect of gender, the results failed to confirm Hypotheses 5, 6, and 7. Gender did not seem to affect the relationship between previous telework experience and quality of life during a lockdown. For Hypothesis 6, gender seemed to affect the relationship between telework frequency and stress (β = -0.14; p <= 0.01). Thus, among full-time teleworkers during the lockdown, women suffered less stress than did men, a finding that invalidates Hypothesis 6. For Hypothesis 7, gender seemed to affect the relationship between presence of young children and stress (β = -0.13; p <= 0.01). Thus, among teleworkers with young children during the lockdown, women suffered less stress than did men, a finding that invalidates Hypothesis 7. These relationships appear in Figures 4 and 5. The relationship between telework frequency and stress was significantly negative for women [t (551) = -4.063, p <= 0.001] and non-significant for men [t (551) = 1.588, N.S.]. Thus, during the lockdown, full-time telework reduced stress only for women (Figure 4). Among teleworkers during the lockdown, presence of young children seemed to increase stress in men [t (551) = 2.032, p <= 0.05] and decrease it in women [t (551) = -3.184, p <= 0.001]. It seems that male teleworkers during the lockdown suffered more stress if they were working in the presence of young children (Figure 5).

Figure 1

Interaction between Telework Frequency and Presence of Young Children for Sleep Quality during Lockdown

Figure 2

Interaction between Telework Frequency and Presence of Young Children for Motivation

Figure 3

Interaction between Telework Frequency and Presence of Young Children for Ability to Undertake Projects

Figure 4

Interaction between Telework Frequency and Gender for Stress

Figure 5

Interaction between Presence of Young Children and Gender for Stress

Discussion

Our aim was to explore how remote work during the pandemic lockdown affected workers psychologically and with respect to their lifestyles. While previous studies have examined the impact of telework, they were done during “quiet periods” without major upheavals and before the unprecedented COVID-19 crisis. Pérez et al. (2004), Illegems and Verbeke (2004), and others such as Martínez‐Sánchez et al. (2007) have identified the fundamental impact that previous experience has on a worker’s commitment to adopt and use telework. Additionally, the ease of use of telework solutions tends to reduce a worker’s perceived isolation and workload (Golden et al., 2008).

In line with the literature, we hypothesized that people less accustomed to telework would have a poorer quality of life due to their lack of control and ability to handle this type of work and would experience more negative impacts than would those familiar with telework. We assumed that people used to telework would experience fewer changes in their lifestyle than would people not used to this work arrangement. Against our expectations, even though the respondents reported that their overall quality of life had declined during the lockdown, previous telework experience did not have a consistent impact on lifestyle.

Being abruptly placed under a lockdown generates a feeling of isolation that equally affects teleworkers with or without previous telework experience. Indeed, the lockdown reduced the quality of life of all teleworkers, regardless of how much previous telework experience they had. It is clear that the pandemic, as well as restrictive lockdown measures, had a significant impact on the quality of life and mental health of individuals (Hallin, 2020; Even, 2020). The lockdown exacerbated teleworkers’ difficulties in keeping their work and personal responsibilities separate. This may also explain why previous telework experience did not reduce all of the negative lockdown effects and why it was not possible to show a direct relationship between all of the variables under study and previous telework experience. According to Raišienė et al. (2020), people with minimal telework experience before the pandemic underestimated the impact of telework during the lockdown compared to those without experience. Those with a lot of experience before the pandemic were the same ones who noted more drawbacks during the lockdown. Those who were able to telework part-time (two days a week) valued the advantages over the disadvantages compared to those who were forced to telework full-time (Hallin, 2020). Similarly, older generations who had teleworked part-time previously and who switched to full-time telework during the lockdown were least satisfied with telework (Raišienė et al., 2020). This reality partly explains the results of the analyses of telework frequency and its impact on the variables used in this study.

Despite this general finding, a difference was observed between different levels of pre-lockdown telework experience: respondents had a greater desire to surf the Internet aimlessly if they had little or no familiarity with telework. They were more likely to have trouble staying focused on their job and surfed the Internet with no specific goal. This finding is in line with Rubin et al. (2020) and (Hallin, 2020). Furthermore, telework frequency during the pandemic was negatively related to stress, perhaps because full-time teleworkers were freer to manage their daily work and manage stress. It is likely that telework, which is new and unusual for this category of employee, can hamper one’s autonomy and ability to undertake tasks or projects because the employee fears making a mistake or because no one else is organizing the work. Such feelings will depend on one’s sense of control and self-efficacy when managing the challenge of remote work (Raghuram, Wiesenfeld, & Garud, 2000). Groups of employees who are used to telework probably feel more empowered and competent and have a greater sense of personal efficiency, since they are used to such a work arrangement, i.e., remote work and communication tools. This explanation is consistent with Park and Cho (2020) and Silva-C (2019), who showed how previous telework experience impacts the empowerment of workers and their ability to manage social isolation. When people are more comfortable with telework, they are probably better able to undertake projects on their own and project themselves into the future because their work situation is not so different from the way it was before the lockdown. They may also be more resilient because they have experience in dealing with the telework challenges caused by the pandemic (Hamouche, 2020).

Our results also show how people accustomed to telework were less inclined to be distracted and surf the Internet aimlessly. People used to telework have therefore probably developed efficient work methods to be productive even without the constraints of an in-person work setting. This may not be the case for someone who is unaccustomed to working remotely and who finds it more challenging to concentrate on their work assignments. More than ever, the Internet has impacted the concentration of workers who are not inclined to telework. This is consistent with research findings showing that telework during a lockdown may impact worker efficiency more than telework in other contexts (Hallin, 2020; Jaiswal & Arun, 2020; Rubin et al., 2020). Even without the pandemic, such a situation could lead to personality disorders due to inattention and distraction. These effects were most likely exacerbated by the pandemic and social isolation (Galanti, Guidetti, Mazzei, Zappalà, & Toscano, 2021). Many other distractions, such as having other family members at home during the pandemic, could also explain the drop in productivity (Hallin, 2020). This situation appears to have been aggravated by lack of experience with telework before the lockdown and lack of previously developed work habits that would favour productivity in a telework context.

Our results seem to support those earlier findings. Indeed, they suggest that having young children at home during a lockdown impacts a teleworker’s quality of life and that this impact becomes even more critical as the frequency of telework increases. If parents are forced to telework while caring for children under 12 at home because the schools and daycares are closed, they may face additional challenges to their ability to focus on their tasks and do them well. Life is made more complex by work overload, family responsibilities, and the need to care for young children, and this complexity generates conflicts in work-life balance and impacts performance and concentration (Hamouche, 2020). Our study shows that remote work can increase stress and anxiety about losing one’s job. This finding is particularly true for women, who reported being more stressed than others, and has been validated by other research (Adisa et al., 2021). The increase in stress may be due to women teleworkers having to work in the evening or at night when their children are asleep, a situation that reduces sleep quality and subsequent motivation. These factors, along with behaviours related to inability to concentrate on specific tasks, such as purposeless surfing on the Internet, are responsible for the reduced work performance.

Our results nonetheless provide a more nuanced picture of the general context of women doing telework. During a lockdown, stress is lower in women who have a higher frequency of telework; this does not seem to be the case for men. In addition, men who work from home seem to adapt less well to the presence of young children during a lockdown. These results confirm those of Raišienė et al. (2020), who found that men did not adapt as well to full-time telework during a lockdown, with the result that role conflict was worse for them than for women. They felt more disturbed by other family members and less able to perform. They also found it difficult to reconcile their dual roles of work and family management. Apparent difficulties with self-management also suggest that men adapt more poorly to the reality of telework during a lockdown; they see career success as being more linked to a traditional male lifestyle (Raišienė et al., 2020). These findings are also in line with those of Afonso, Fonseca, and Teodoro (2021), who studied anxiety, stress, and depression in teleworkers during the pandemic and who suggested that productivity was lower for men than for women. Such outcomes are explained by the dissolution of traditional work-life balance, by an increase in family conflicts, and by social isolation, which men and women experience equally.

To help prevent role conflict between work and private life, organizations could strongly suggest that employees create physical boundaries between their work environment and the other rooms of the house (Bentley et al., 2016). They should not work in the dedicated living spaces of their homes. They should also define and respect the time they allocate to working and the time they allocate to private life. Communication with family members is also crucial to avoid role conflicts between private life and work life (Wang, Liu, Qian, & Parker, 2021). When employees work from home, they must psychologically leave work at the end of the day, a disconnect that can be all the more challenging because they are not used to it and because work is only a few steps away. The boundary is not only physical but also psychological, and employees must be educated about the psychological boundaries they must set in order to know when to stop and avoid becoming overloaded (Even, 2020; Golden, 2006; Golden & Eddleston, 2020; Golden et al., 2008). To help employees set these boundaries, organizations can advocate for the right to disconnect, even if this right is not recognized in Canada. Valuing this right could prevent overload by allowing employees to keep their work time separate from their rest time (Mello, 2007).

Finally, beyond these results, we found that respondents who succeeded in staying motivated during the lockdown were still able to sleep well and undertake projects. Sleep quality appears to be essential, as it is also associated with lower irritability and a greater capacity to handle projects. When well rested, workers can stay more focused on their goals and are less likely to surf the Internet aimlessly. These findings are consistent with those of Brooks et al. (2020) and Brem et al. (2021).

Conclusion

Our study shows that teleworkers, particularly those belonging to vulnerable subgroups, experienced a decline in the quality of their life and health during the lockdown. Many challenges faced those who were unaccustomed to telework and had children at home. Considering that telework is here to stay, society, employers, and teleworkers all have roles to play if they wish to adapt and thrive under rapidly changing working conditions. These roles include amending Canadian labour laws on telework, raising awareness about its potential negative impacts, and implementing remedies for such impacts while keeping in mind that not all teleworkers have the same reality. This can be done by acting upstream on potential problems and by being proactive in addressing mental health. Finally, we must adapt, change, evolve, inform, train, understand, and, above all, not neglect the negative effects that the rapid introduction of telework can have on individuals who have no experience with working from home and whose working environments are not optimal. Work-life balance seems to be fundamental for teleworkers. Success depends on having a room specifically for work and being able to make family members understand the need to concentrate. Although women are frequently affected by telework challenges, particularly when they have young children, our results include unexpected findings about how men manage stress and, more broadly, about how they manage telework with young children at home. These outcomes raise exciting and as yet unexplored avenues for research.

Our study has some limitations. First, it used a non-probabilistic convenience sample. Second, the data were collected over a single measurement period (the lockdown) and required respondents to assess their previous quality of life. In the future, our study could be repeated to see how the situation of workers has evolved. A repeat study would provide a fascinating longitudinal perspective, given the changes and restrictions due to the pandemic. Third, the sample size limits our ability to generalize the findings to other jurisdictions in English Canada, which managed the lockdown and telework differently. This limitation was mitigated, however, by the relative similarity of lockdown enforcement in all Canadian provinces.

Telework is not the same during a lockdown as it is at other times. It is a rare and complex phenomenon. During the pandemic lockdown, it created difficulties completely unlike those associated only with telework. The work environment was turned upside-down even among people used to telework, whose quality of life generally suffered. They experienced isolation, although this outcome must be dissociated from telework itself. Organizations can use our findings to anticipate the constraints they will face if many teleworkers decide to keep working remotely after the pandemic. We have shown that telework is not experienced in the same way by men and women workers and by those with family responsibilities. It is an opportunity for some, and a constraint for others. Managers have to understand the psychological profile of their employees and devise work methods and means of communication accordingly. To maintain a high level of engagement in telework (particularly during a lockdown), managers should communicate more often with their employees. By using online communication channels, like Slack, Teams, or Workplace, they can keep remote workers engaged and close to the organization. They can also engage in regular online meetings to communicate, share information, and demonstrate their willingness to maintain strong links with teleworkers. Such meetings are an opportunity to clarify goals, missions, and guidelines and thereby reduce social isolation.

Telework is being introduced above all for the benefit of companies. Indeed, as we have previously noted, it is not readily accepted by all workers. The latter need support to reduce their feelings of social isolation and the sense that they are not in the loop. They will need better communication tools to collaborate and coordinate with each other and with management.

Parties annexes

References

- Adisa, Toyin Ajibade, Aiyenitaju, Opeoluwa, & Adekoya, Olatunji David. (2021). The work–family balance of British working women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Work-Applied Management.

- Afonso, Pedro, Fonseca, Miguel, & Teodoro, Tomás. (2021). Evaluation of anxiety, depression and sleep quality in full-time teleworkers. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England).

- Aiken, Leona S, West, Stephen G, & Reno, Raymond R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions: sage.

- Al-Balushi, S., Sohal, A. S., Singh, P. J., Hajri, A. Al, Farsi, Y. M. Al, & Abri, R. Al. (2014). Readiness factors for lean implementation in healthcare settings - a literature review. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 28(2), 135-153.

- Andresen, Elena M, Malmgren, Judith A, Carter, William B, & Patrick, Donald L. (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American journal of preventive medicine, 10(2), 77-84.

- Baert, Stijn, Lippens, Louis, Moens, Eline, Sterkens, Philippe, & Weytjens, Johannes. (2020). How do we think the COVID-19 crisis will affect our careers (if any remain)?

- Baert, Stijn, Lippens, Louis, Moens, Eline, Weytjens, Johannes, & Sterkens, Philippe. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis and telework: A research survey on experiences, expectations and hopes.

- Bailey, Diane E, & Kurland, Nancy B. (2002). A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 23(4), 383-400.

- Baines, Susan, & Gelder, Ulrike. (2003). What is family friendly about the workplace in the home? The case of self‐employed parents and their children. New Technology, Work and Employment, 18(3), 223-234.

- Bakker, Arnold B, & Demerouti, Evangelia. (2007). The job demands‐resources model: State of the art. Journal of managerial psychology.

- Bélanger, France. (1999). Workers' propensity to telecommute: An empirical study. Information & management, 35(3), 139-153.

- Belzunegui-Eraso, Angel, & Erro-Garcés, Amaya. (2020). Teleworking in the Context of the Covid-19 Crisis. Sustainability, 12(9), 3662.

- Bentley, TA, Teo, STT, McLeod, L, Tan, F, Bosua, R, & Gloet, M. (2016). The role of organisational support in teleworker wellbeing: A socio-technical systems approach. Applied Ergonomics, 52, 207-215.

- Bianchi, Suzanne M, Sayer, Liana C, Milkie, Melissa A, & Robinson, John P. (2012). Housework: Who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Social forces, 91(1), 55-63.

- Bouziri, Hanifa, Smith, David RM, Descatha, Alexis, Dab, William, & Jean, Kévin. (2020). Working from home in the time of covid-19: how to best preserve occupational health? Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 77(7), 509-510.

- Brem, Alexander, Viardot, Eric, & Nylund, Petra A. (2021). Implications of the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak for innovation: Which technologies will improve our lives? Technological forecasting and social change, 163, 120451.

- Brooks, Samantha K, Webster, Rebecca K, Smith, Louise E, Woodland, Lisa, Wessely, Simon, Greenberg, Neil, & Rubin, Gideon James. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The lancet, 395(10227), 912-920.

- CRHA. (2020). Baromètre RH express : rapport des résultats – gestion du télétravail, (CRHA). In Ordre des conseillers en ressources humaines agréés (Ed.). Retrieved from http://www.portailrh.org/barometrerh/doc/CRHA_teletravail_rapport-Resultat-1906-2020.pdf

- de Graaff, Thomas, & Rietveld, Piet. (2004). ICT and substitution between out-of-home and at-home work: the importance of timing. Environment and Planning A, 36(5), 879-896.

- Durieux, Eve. (2020). Télétravail et confinement, vers une coexistence vivable. Ministère de l'intérieur,

- Elhai, Jon D, Levine, Jason C, Dvorak, Robert D, & Hall, Brian J. (2016). Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 509-516.

- Even, Angela. (2020). The Evolution of Work: Best Practices for Avoiding Social and Organizational Isolation in Telework Employees. Available at SSRN 3543122.

- Frey, Carl Benedikt, & Osborne, Michael A. (2017). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technological forecasting and social change, 114, 254-280.

- Galanti, Teresa, Guidetti, Gloria, Mazzei, Elisabetta, Zappalà, Salvatore, & Toscano, Ferdinando. (2021). Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: The impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine, 63(7), e426.

- Gjoneska, Biljana, Potenza, Marc N, Jones, Julia, Corazza, Ornella, Hall, Natalie, Sales, Célia MD, . . . Werling, Anna Maria. (2022). Problematic use of the internet during the COVID-19 pandemic: Good practices and mental health recommendations. Comprehensive psychiatry, 112, 152279.

- Golden, Timothy D. (2006). Avoiding depletion in virtual work: telework and the intervening impact of work exhaustion on commitment and turnover intentions. Journal of vocational behavior, 69(1), 176-187.

- Golden, Timothy D, & Eddleston, Kimberly A. (2020). Is there a price telecommuters pay? Examining the relationship between telecommuting and objective career success. Journal of vocational behavior, 116, 103348.

- Golden, Timothy D, Veiga, John F, & Dino, Richard N. (2008). The impact of professional isolation on teleworker job performance and turnover intentions: does time spent teleworking, interacting face-to-face, or having access to communication-enhancing technology matter? Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1412.

- Haddad, Hebba, Lyons, Glenn, & Chatterjee, Kiron. (2009). An examination of determinants influencing the desire for and frequency of part-day and whole-day homeworking. Journal of Transport Geography, 17(2), 124-133.

- Halford, Susan. (2005). Hybrid workspace: Re‐spatialisations of work, organisation and management. New Technology, Work and Employment, 20(1), 19-33.

- Hallin, Henning. (2020). Home-Based Telework During the Covid-19 Pandemic. In.

- Hamouche, Salima. (2020). COVID-19 and employees’ mental health: stressors, moderators and agenda for organizational actions. Emerald Open Research, 2.

- Harris, Lynette. (2003). Home‐based teleworking and the employment relationship: Managerial challenges and dilemmas. Personnel Review.

- He, Sylvia Y, & Hu, Lingqian. (2015). Telecommuting, income, and out-of-home activities. Travel Behaviour and Society, 2(3), 131-147.

- Hsieh, Yu-Chen, Tsai, Wang-Chin, & Hsia, Yu-Chi. (2020). A Study on Technology Anxiety Among Different Ages and Genders. Paper presented at the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction.

- Illegems, Viviane, & Verbeke, Alain. (2004). Telework: what does it mean for management? Long range planning, 37(4), 319-334.

- Iscan, Omer Faruk, & Naktiyok, Atilhan. (2005). Attitudes towards telecommuting: the Turkish case. Journal of Information Technology, 20(1), 52-63.

- Jaiswal, Akanksha, & Arun, C Joe. (2020). Unlocking the COVID-19 Lockdown: Work from Home and Its Impact on Employees.

- Lenzo, Vittorio, Quattropani, Maria C, Sardella, Alberto, Martino, Gabriella, & Bonanno, George A. (2021). Depression, anxiety, and stress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak and relationships with expressive flexibility and context sensitivity. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 348.

- Lister, Kate, & Harnish, Tom. (2019). Telework and its effects in the United States. In Telework in the 21st Century: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Martínez‐Sánchez, Angel, Pérez‐Pérez, Manuela, De‐Luis‐Carnicer, Pilar, & Vela‐Jiménez, María José. (2007). Telework, human resource flexibility and firm performance. New Technology, Work and Employment, 22(3), 208-223.

- Maruyama, Takao, & Tietze, Susanne. (2012). From anxiety to assurance: Concerns and outcomes of telework. Personnel Review.

- Mello, Jeffrey A. (2007). Managing telework programs effectively. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 19(4), 247-261.

- Mokhtarian, Patricia L, Bagley, Michael N, & Salomon, Ilan. (1998). The impact of gender, occupation, and presence of children on telecommuting motivations and constraints. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 49(12), 1115-1134.

- Nakrošienė, Audronė, Bučiūnienė, Ilona, & Goštautaitė, Bernadeta. (2019). Working from home: characteristics and outcomes of telework. International Journal of Manpower.

- Nauman, Shazia, Raja, Usman, Haq, Inam Ul, & Bilal, Waqas. (2019). Job demand and employee well-being: A moderated mediation model of emotional intelligence and surface acting. Personnel Review.

- Nielsen, Morten Birkeland, Christensen, Jan Olav, & Knardahl, Stein. (2021). Working at home and alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 14, 100377.

- Nurul Habib, Khandker M, Sasic, Ana, & Zaman, Hamid. (2012). Investigating telecommuting considerations in the context of commuting mode choice. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 6(6), 362-383.

- Park, Seejeen, & Cho, Yoon Jik. (2020). Does telework status affect the behavior and perception of supervisors? Examining task behavior and perception in the telework context. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1-26.

- Pérez, Manuela Pérez, Sánchez, Angel Martínez, de Luis Carnicer, Pilar, & Jiménez, María José Vela. (2004). A technology acceptance model of innovation adoption: the case of teleworking. European Journal of innovation management.

- Peters, Pascale, Tijdens, Kea G, & Wetzels, Cecile. (2004). Employees’ opportunities, preferences, and practices in telecommuting adoption. Information & management, 41(4), 469-482.

- Pitafi, Abdul Hameed, Rasheed, Muhammad Imran, Kanwal, Shamsa, & Ren, Minglun. (2020). Employee agility and enterprise social media: The Role of IT proficiency and work expertise. Technology in Society, 63, 101333.

- Prodanova, Jana, & Kocarev, Ljupco. (2021). Is job performance conditioned by work-from-home demands and resources? Technology in Society, 66, 101672.

- Radloff, Lenore S. (1977). A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychol Measurements, 1, 385-401.

- Raghuram, Sumita, Wiesenfeld, Batia, & Garud, Raghu. (2000). ADJUSTMENT TO TELECOMMUTING: ROLE OF SELF-EFFICACY AND STRUCTURING. Paper presented at the Academy of management proceedings.

- Raišienė, Agota Giedrė, Rapuano, Violeta, Varkulevičiūtė, Kristina, & Stachová, Katarína. (2020). Working from Home—Who is Happy? A Survey of Lithuania’s employees during the COVID-19 quarantine period. Sustainability, 12(13), 5332.

- Rubin, Ori, Nikolaeva, Anna, Nello-Deakin, Samuel, & te Brömmelstroet, Marco. (2020). What can we learn from the COVID-19 pandemic about how people experience working from home and commuting. Centre for Urban Studies, University of Amsterdam Working Paper.

- Sener, Ipek N, & Reeder, Phillip R. (2012). An examination of behavioral linkages across ICT choice dimensions: copula modeling of telecommuting and teleshopping choice behavior. Environment and Planning A, 44(6), 1459-1478.

- Silva-C, Alejandro. (2019). The attitude of managers toward telework, why is it so difficult to adopt it in organizations? Technology in Society, 59, 101133.

- Singh, Palvinder, Paleti, Rajesh, Jenkins, Syndney, & Bhat, Chandra R. (2013). On modeling telecommuting behavior: Option, choice, and frequency. Transportation, 40(2), 373-396.

- Song, Younghwan, & Gao, Jia. (2020). Does telework stress employees out? A study on working at home and subjective well-being for wage/salary workers. Journal of Happiness studies, 21(7), 2649-2668.

- Taskin, Laurent, & Bridoux, Flore. (2010). Telework: a challenge to knowledge transfer in organizations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(13), 2503-2520.

- Thatcher, Sherry MB, & Zhu, Xiumei. (2006). Changing identities in a changing workplace: Identification, identity enactment, self-verification, and telecommuting. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 1076-1088.

- Vayre, Émilie. (2019). Les incidences du télétravail sur le travailleur dans les domaines professionnel, familial et social. Le travail humain, 82(1), 1-39.

- Wang, Bin, Liu, Yukun, Qian, Jing, & Parker, Sharon K. (2021). Achieving effective remote working during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied psychology, 70(1), 16-59.

- Wiesenfeld, Batia M, Raghuram, Sumita, & Garud, Raghu. (1999). Communication patterns as determinants of organizational identification in a virtual organization. Organization Science, 10(6), 777-790.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Interaction between Telework Frequency and Presence of Young Children for Sleep Quality during Lockdown

Figure 2

Interaction between Telework Frequency and Presence of Young Children for Motivation

Figure 3

Interaction between Telework Frequency and Presence of Young Children for Ability to Undertake Projects

Figure 4

Interaction between Telework Frequency and Gender for Stress

Figure 5

Interaction between Presence of Young Children and Gender for Stress

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Sociodemographic and Telework Profile of Respondents

Table 2

Quality of Life Before and During Lockdown

Table 3

Correlation Matrix

Table 4

Regression Analyses between Sociodemographic and Telework Profile Variables, for Quality of Life Indicators