Article body

Despite its prominent place in American food culture, there is very little uniquely “American” about apple pie. The popular dessert relies upon the English cookery technique of baking a filling between two crusts as a means of preserving food for a short time. While sugar is New World, the combination of other ingredients is Old World: apples, lemon, and various combinations of spices. The use of exotic spices like cinnamon, mace, nutmeg, and cloves in pumpkin pie associates the dish with ancient trade routes between Europe and the east. Further, these spices hint at a relationship with the commonly recognized discovery of the Americas, the abortive search for a western route to the East Indies.[1] Cookbooks published in the United States and Canada during the nineteenth century reveal how Old World culinary techniques and New World produce combined to create a North American cuisine that was simultaneously unique and heavily indebted to European influences.

American author Sarah J. Hale’s 1852 edition of The Ladies’ New Book of Cookery is representative of this development. Hale’s cookbook included two recipes for apple pie, one marked as English and the other as American. Since apple pie is a long-established English baked good brought by the colonists to the New World, it is unsurprising that the English and American versions of apple pie provided by Hale are similar. Both call for apples sweetened with sugar and flavoured with lemon and spices between two layers of pastry baked in a moderate oven. The most significant difference is that the American pie is spiced with just cinnamon, while the English recipe calls for cloves and nutmeg. More significant differences emerge on the next page, where Hale provides two recipes for pumpkin pie.

Figure 1

American and English Pumpkin Pie Recipes, The Ladies’ New Book of Cookery, Sarah J. Hale, H. Long & Brother, New York, 1852. Feeding America: The Historic American Cookbook Project. Michigan State University Libraries. East Lansing, MI 48824.

Pumpkin pie possibly emerged from early American cooks making do with the ingredients available to them. Since pumpkins have a similar consistency to apples, some food historians have suggested cooks substituted them in traditional apple dishes.[2] In Hale’s cookbook, the English version is reminiscent of the earliest versions of pumpkin pie composed of stewed pumpkin baked in a single pie shell and made palatable with sweeteners and spices. The American version is closer to the dessert item recognized today, a pumpkin custard flavoured with molasses, cinnamon and ginger. Hale’s 1852 debut novel, Northwood, declared pumpkin pie "an indispensable part of a good and true Yankee Thanksgiving" and it is still among the most popular baked goods with 50 million pies baked and consumed in America each year, especially during the holiday season.[3] In The Female Emigrant’s Guide and Hints on Canadian Housekeeping, Catherine Parr Traill discusses the differences between English and North American versions of pumpkin pie, “Now I must tell you, that an English pumpkin-pie, and a Canadian one, are very differently made," she writes, "and I must give preference, most decidedly, to the American dish; which is something between a custard and a cheese-cake in taste and appearance.”[4]

The pumpkin pie described by Traill was not merely an adaptation of American ingredients to an English dish, it also benefited from the culinary melting pot that brought together numerous world cuisines in North American kitchens. Waves of immigrants of the 19th century brought new culinary influences to both Canada and America, while recipes reflected these increasingly multinational influences. Most significantly, the influence of European immigrants assisted in the evolution of North American pie to the decadent desserts enjoyed today. Pie was suited to the primitive conditions of early settlement, since pies allowed the cook to stretch meagre provisions and the crust, which required less flour than bread and no special equipment to bake, could preserve the filling for a short time. In early North America, pie was a decidedly practical dish. In the nineteenth century, pie was slowly transforming from a pragmatic means of short-term food preservation to baked goods showcasing a variety of fillings and expressly prepared as a sweet treat. Better conditions and the influence of more refined European pie making techniques brought by French and German immigrants revolutionized pie fillings with their sophisticated use of spices, sweeteners, and native ingredients to create delicious fillings of fruit, preserves, and custards. French traditions particularly transformed the dense suet and flour crust of English pies through the introduction of butter into piecrusts. Pumpkin pie, featuring a New World crop prized by First Nations cultures, prepared in an Old World manner influenced by several national cuisines, makes a better candidate for an iconic North American dessert.

Food and cultural identity are inextricably linked. We are not only what we eat, but how, where, when and why we eat. In creating national culture, as many scholars have argued, cookbooks play an essential role in transforming regionalized cuisines and peoples into a unified whole.[5] Compilations of practical receipts, special occasion cooking, and housekeeping advice, cookbooks “are an expression of the values and aspirations of the people who produced them.”[6] Prior to the American Revolution, a shared cultural background and the need to adapt culinary techniques transferred from Europe to new foodstuffs available in North America forged a uniquely North American cuisine that persisted into the nineteenth century. Scholars have argued that the separation between Canada and the United States should not be viewed as a clean break, but rather “a line of ragged connections” particularly in the decades following the American Revolution.[7] The international border, rather than an impediment to cultural interaction and exchange, should be viewed as a permeable boundary. Much of traditional history follows national boundaries and practitioners of the borderlands approach argue these artificially imposed boundaries obscure the similarities, connections, and relationships of peoples living on either side of an international border. A rich scholarship outlines the value of viewing Canada and the northeastern United States, especially New England and New York, as a borderlands region in the nineteenth century.[8] In the decades before Confederation, and many scholars have argued persisting to the present, Canada and America maintained social, economic, political, and cultural ties. Lingering spheres of influence from the American colonial period, as well as the Loyalist experience, westward migration patterns, economic partnerships, and a shared culture forged these lingering connections.[9] Even as the political chasm widened following the War of 1812, there were more cultural similarities than differences between Americans and Canadians.

A shared print culture, facilitated largely by U.S. refusal to acknowledge international copyright, further connected Canada and America into the nineteenth century. The availability of cheap American reprints of foreign works on both sides of the border served to intergrate markets. Amanda Claybaugh argues the U.S. and Great Britain shared an intimate literary marketplace and the same is true of Canada and America.[10] American texts had a profound influence north of the border where they were both imported and reprinted. Beginning around 1750, American imports became common in the Canadian marketplace. As Canadian printers slowly established themselves, reprints or compilations of American texts sold briskly until the mid-19th century.[11]

This cross-border sharing of cuisine and literature was also a natural extension of the intermingling of cuisine and culture that existed between countries and continents for centuries. Food historian Karen Hess described Hannah’s Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, first published in London in 1747, as “the most English of cookbooks . . . the most American of cookbooks.”[12] Early settlers at Jamestown imported Gervase Markham’s English Housewife to instruct the colony’s female inhabitants on cookery, housekeeping, and other womanly duties. The Art of Cookery was used in George Washington and Thomas Jefferson’s households and translated into French by Benjamin Franklin. Eliza Smith’s The Compleat Housewife, Susannah Carter’s The Frugal Housewife, and Maria Eliza Rundell’s A New System of Domestic Cookery were common fixtures in colonial kitchens. Until the early nineteenth century, English cookbooks were regularly imported and reprinted in the colonies without any changes to adapt them to a colonial audience.[13]

This essay examines a period of relative fluidity and adaptablity in cuisine and literature between Canada and the United States. Bookended by the publication of American Cookery in 1796 by Amelia Simmons and Catharine Parr Traill’s The Female Emigrant’s Guide in 1854, this period represents a literary and, I argue, culinary culture “that was regional in articulation and transnational in scope.”[14] The first cookbook written and published in the United States, American Cookery, hailed by one historian as “another declaration of American independence” asserting a new American system of cookery.[15] However, cookbooks from this period reveal more continuity and persistence across national borders than differentiation. Texts that literally proclaimed national exceptionalism on their covers, American Practical Cookery, The American Lady’s System of Cookery, The Canadian Housewife’s Manual of Cookery, and The Canadian Settler’s Guide contained remarkably similar collections of recipes despite their claims to be particularly suited to a Canadian or American audience. The appearance of “good republican dishes” in Canadian reprints and the popularity of texts branded as “American” on both sides of the border complicates the narrative of separation between Canada and the United States.

British culture, particularly British foodways would continue to have a far-reaching influence on American tastes and habits in the years immediately following the Revolution, British texts like Maria Eliza Ketelby Rundell’s A New System of Domestic Cookery and Susannah Carter’s The Frugal Housewife were enduring classics in the American marketplace, reprinted in American cities into the 1830s.[16] In the 1860s and 1870s, both American and Canadian housekeepers would rely on Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management.[17] During this period, Americans sought to define themselves as a distinctive people. Customs around food and dining were essential to this development. Americans wanted American food. This mania for all things American led to a greater embrace of American ingredients and the naming of new recipes to honour American statesmen or places of origin. Washington Cake, Madison Whims, Jackson Jumbles, and the old favourite Election Cake appeared in printed and manuscript cookbooks alike.[18] As food became increasingly Americanized, so did the rituals surrounding serving and enjoying a meal. The American marketplace became increasingly flooded with affordable ceramics depicting significant scenes from American history or American places. Thus, republican Americans could enjoy their roast turkey on dishes depicting the battle between the Chesapeake and the Shannon or serve corn pudding in a dish celebrating American unity and independence. It was conveient for diners to ignore that both the culinary traditions and the ceramics originated in Great Britain. Of course, as Americans sought to define themselves as Americans and sought, on the surface at least, to push away British influence, the cultural ties between Canada and Great Britain strengthened as Canadians sought to define themselves against America. The simultaneous influence of American and British culture can be glimpsed in Traill’s use of both systems of measure in The Canadian Emigrant’s Guide. Food remained a cultural bridge in the Anglo-American world despite the separation brought by the American Revolution and, later, the War of 1812.

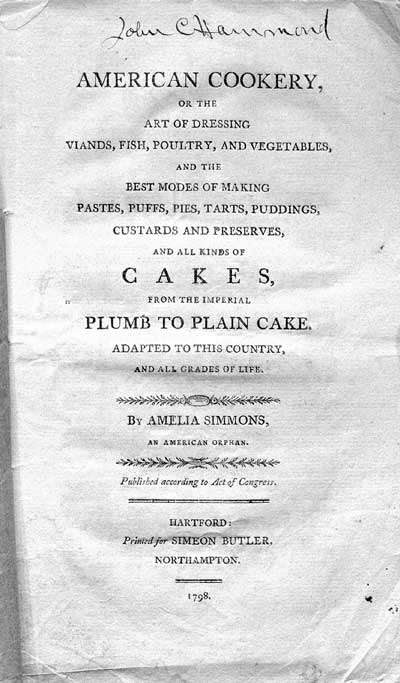

Figure 2

Title Page, American Cookery, Amelia Simmons, Printed for Simeon Butler, Northampton, Hartford, 1798. Feeding America: The Historic American Cookbook Project. Michigan State University Libraries. East Lansing, MI 48824.

The desire for an "American" dining experience would influence the production of cookbooks. American Cookery was the first distinctly nationalistic cookbook published in North America. Described as, “adapted to this country,” Simmons’ text prioritized American ingredients and, for example, hinted at emerging American taste preferences with molasses rather than treacle as the sweetener in gingerbread.[19] Recipes utilizing pearlash and references to Dutch words like slaw and "cooky[sic]" are evidence of culinary and language innovations in American culture.[20] Recipes for Independence Cake and Federal Pan Cake, among others, are suggestive of the development of a distinctly American and self-consciously republican identity.

The popularity of American Cookery, suggested by multiple editions, pirated copies, and the appearance of Simmons’ recipes in other texts, led North American publishers to produce more cookbooks “adapted to this country.” The sincerity of their efforts varied. Sarah J. Hale in the Ladies New Book of Cookery and Catharine E. Beecher in Miss Beecher’s Domestic Receipt Book devoted pages to describing and defining the differences between British women and American ladies. Other works were clearly produced to appeal to the market. Most often, nods to nationalism took the form of specific attention to local ingredients. Eliza Leslie’s New Directions for Cookery, first published in Philadelphia in 1837, provides numerous examples of developing American cuisine in recipes for Sassafras Beer, Green Corn Pudding, Clam Soup, Hominy, Ochra Soup, Pepper Pot, Cat-Fish Soup, and Indian Pudding. Leslie’s preface to the work explained that in “designing it as a manual in American housewifery, she [the author] has avoided the insertion of any dishes whose ingredients cannot be procured on our side of the Atlantic.”[21] Cookbooks written and published in Canada, relatively rare before 1860, likewise focused on local ingredients. Canadian published texts like The Female Emigrant’s Guide and Hints on Canadian Housekeeping (1854) and The Frugal Housewife’s Manual (1840) are similarly focused on North American produce including corn, wheat, potatoes, tomatoes, pumpkins, beans and many others.

In other instances, the appeal to a developing national identity was undoubtedly a veneer. A means to achieve commercial success, rather than the result of a desire to present the culinary practices best suited to the developing American or Canadian sense of identity in the kitchen. English author Maria Eliza Ketelby Rundell’s 1806 text, A New System of Domestic Cookery, was consistently reprinted in the United States.

Often, the text was marketed for the American marketplace simply by changing the title, such as American Domestic Cookery or The Experienced American Housekeeper, with little to no changes to the text’s contents. An 1803 edition of Susannah Carter’s enduringly popular Frugal Housewife, a classic English cookery book, published in New York included a brief appendix described as, “Containing Several Recipes Adapted to the American Mode of Cooking.” This appendix contained recipes suited for North American kitchens and includes such North American classics as Indian Pudding, Pumpkin Pie, Dough Nuts, Cranberry Tarts, molasses-sweetened Gingerbread, and instructions for making maple sugar and raising turkeys. Most likely, the appendix was added to the text by the American publisher to appeal to American cooks.

Figure 3

Title Page, The Cook Not Mad; or Rational Cookery, author unknown, Knowlton & Rice, Watertown, N.Y., 1831. Feeding America: The Historic American Cookbook Project. Michigan State University Libraries. East Lansing, MI 48824.

It was not uncommon for cookbooks to simply declare their association to a particular nationality, either in the title or preface, despite presenting recipes that were decidedly indebted to English culinary traditions and differed little from English texts also available. Eliza Leslie’s Seventy-Five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes, and Sweetmeats, would claim, “the receipts in this book are, in every sense of the word, American,”[22] despite the inclusion of classically English recipes like Queen Cake, Trifle, and Plum Pudding as well as several French-influenced desserts such as Charlotte Russe and Blancmange. The first English-langage cookbook published in Canada was a reprint of an anonymous text first published in Upstate New York, The Cook Not Mad; or Rational Cookery.[23] Like most printed cookbooks of its era, The Cook Not Mad is a compilation of recipes from American and English cookbooks, many verbatim copies. The preface to the Watertown, NY edition claims the text is adapted to the taste and habits of the “American Publick,” a claim evidenced by recipes using distinctly North American products like turkey, pumpkin, codfish, cranberries, and cornmeal. The Canadian edition is an exact copy of the original New York publication except for the title page which described the included recipes as “embracing . . . cooking, in its general acceptation, to the taste, habits, and degrees of luxury prevalent with the Canadian Public.”[24] The unedited preface professes the belief that “every nation has its peculiar dishes” and “a Work of Cookery should be adapted to the meridian in which it is intended to circulate.”[25] This discussion concludes with comments on the impropriety of introducing “into a work intended for the American Public such English, French, and Italian methods of rendering things indigestible.”[26]

In avoiding the evils of foreign culinary influences, both editions of The Cook Not Mad provide recipes for “good republican dishes,” presumably recipes utilizing North American ingredients or with names related to the American political system like Washington Cake, Jackson Jumbles, and Federal Cake.[27] Despite a desire to escape the pernicious influence of English foodways, most of the cake and pudding recipes are English classics, including Sunderland, Marlborough, Nottingham, and Whitpot puddings and Queen’s, Derby, Danbury, and Turnbridge Cakes. Aside from ingredients, there is little uniquely American about The Cook Not Mad. Indeed, the inclusion of classic English dishes may explain the success of The Cook Not Mad in the Canadian market. The Cook Not Mad provides a particularly compelling example of a borderlands text, the geographical proximity of Watertown and Kingston allowed the text to circulate across political boundaries, despite its self-conciously republican identity. Regional similarities between upstate New York and the Niagara region made the recipes compiled in The Cook Not Mad a useful reference on both sides of the border. Whether marketed as suited for American or Canadian cooks, The Cook Not Mad provided a North American system of cooking that could function transnationally.

The development of a shared North American foodways contributed to the success of American cookbooks in Canada. The most popular Canadian cookbooks published before 1870 were largely American reprints. The earliest cookbooks both written and published in Canada served as guidebooks for newly arrived immigrants. These texts borrowed heavily from American cookbooks. The Frugal Housewife’s Manual published in 1840 is largely based on Lydia Maria Child’s The Frugal American Housewife and provides an example of shared American-Canadian foodways.[28]

Published in Toronto 1840, The Frugal Housewife’s Manual was the first cookbook written and published in Canada. Authored by an anonymous woman from Grimsby, a small settlement of primarily United Empire Loyalists and their descendants in the Niagara region, The Frugal Housewife’s Manual evokes, “the domestic culture of rural Anglo-Canada in the mid-1800s.”[29] Compiled from from other popular cookbooks of the period the Manual contains a few meat and fish recipes that appear to be original. None of the recipes were copied verbatim. The anonymous author added her personal gloss with notes and hints. Small enough to be tucked into an apron pocket for consultation in the kitchen or garden, the cookbook contains seventy-two recipes for cooking and instructions for cultivating twenty-eight vegetables. A.B., the anonymous author, provides recipes to allow a housewife to prepare delicious and wholesome meals from her homegrown produce.

The Frugal Housewife’s Manual bears a marked resemblance to dozens of other cookbooks published by women throughout the northeastern United States between 1830 and 1860. Like American texts, there is an emphasis on recipes for cake. The names of the recipes are suggestive of continued connections with a recipe for Albany Cake and the classic Election Cake. In stating the purpose of her cookbook, A.B. bemoaned the current state of women’s culinary education and claimed, “the design of this little Manual is to put house-keepers in general on an equality in respect to the art of cooking.”[30] American and English texts during this period also address the allegedly sad state of women’s domestic and culinary educations. The author of A New System of Domestic Cookery, popular throughout the Anglo-American world, decried the lack of basic cookery knowledge, “how rarely do we meet with fine melted butter, good toast and water, or well made coffee!”[31]

Despite the strong protestations of American cookbook authors like Beecher, Hale, Child, Simmons, and others, the republication of American texts for Canadian markets with minimal changes to adapt them to the Canadian reader suggests the interchangeability of North American food culture in the 19th century. Canada and the United States were increasingly growing apart politically, but in terms of what people ate and how they prepared it, the two populations continued to have much in common. These similarities allowed Catharine Parr Traill to refer to pumpkin pie as Canadian and American within the same sentence and without confusion. In terms of cuisine, and identity to a certain extent, the differences had not yet emerged. As a symbol of North American foodways, pumpkin pie was simultaneously Canadian and American. A result of the North American culinary melting pot, recipes for pumpkin pie combined Old World culinary techniques with New World ingredients making it a quintessential North American dish.

Appendices

Biographical note

Rachel A. Snell is a PhD candidate in History at the University of Maine. She completed a MA in Early American History at the University of New Hampshire in 2008. Her dissertation project focuses on the everyday experience of domesticity for middle-class women in the northeastern U.S. and English-speaking Canada.

Notes

-

[1]

Pat Willard, “Pies and Tarts” in Andrew F. Smith, ed., The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, vol. II (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 272-3; Abigail Carroll, Three Squares: The Invention of the American Meal (New York: Basic Books, 2013), 43.

-

[2]

Carroll, Three Squares, 17; Sandra L. Oliver, Food in Colonial and Federal America (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2005), 23.

-

[3]

Sarah J. Hale, Northwood; A Tale of New England (Boston: Bowles and Dearborn, 1827), 109; Laura B. Weiss, “Pumpkin Pie” in Andrew F. Smith, ed., The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 482.

-

[4]

Catharine Parr Traill, The Female Emigrant’s Guide and Hints on Canadian Housekeeping (Toronto: MacLear and Co., 1854), 127-8.

-

[5]

Arjun Appadurai, “How to Make a National Cuisine: Cookbooks in Contemporary India,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 30 (1988): 5; James E. McWilliams, A Revolution in Eating Habits: How the Quest for Food Shaped America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 8-9; Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald, America’s Founding Food: The Story of New England Cooking (Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 278.

-

[6]

Elizabeth Driver, Culinary Landmarks: A Bibliography of Canadian Cookbooks, 1825-1949 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), xxix.

-

[7]

John Herd Thompson and Stephen J. Randall, Canada and the United States: Ambivalent Allies (Athens, GA and London: The University of Georgia Press, 2008), 18. Although the geopolitical expanse now known as Canada underwent a succession of designations and organizations during the period under study, for ease of communication it will be referred to simply as “Canada” in this essay.

-

[8]

P.A. Buckner, “The Borderlands Concept: A Critical Appraisal” in Hornsby, Konrad, and Herland, eds. The Northeastern Borderlands: Four Centuries of Interaction (Fredericton, N.B. : Canadian-American Center, University of Maine : Acadiensis Press, 1989), 152-158; Margaret Conrad, “Regionalism in a Flat World,” Acadiensis 35 (Spring 2006), 138-143; Elizabeth Mancke, “Spaces of Power in the Early Modern Northeast,” in Hornsby and Reid, eds. New England and the Maritime Provinces: Connections and Comparisons (Montreal : McGill-Queen's University Press, 2005), 32-49; Harold McGee, “Four Centuries of Borderlands Interaction: It Depends Upon Who Draws the Line and When?” in Hornsby, Konrad, and Herland, eds. The Northeastern Borderlands, 140-148.

-

[9]

Graeme Wynn, “New England’s Outpost in the Nineteenth Century” in Hornsby, Konrad, and Herland, eds. The Northeastern Borderlands, 64-90; John Reid, “An International Region of the Northeast: Rise and Decline, 1635-1762,” in Hornsby, Konrad, and Herland, eds. The Northeastern Borderlands, 10-25; Mancke, “Spaces of Power,” 32-49.

-

[10]

Amanda Claybaugh, The Novel of Purpose: Literature and Social Reform in the Anglo-American World (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2007), 18-20.

-

[11]

Driver, Culinary Landmarks, xvii-xxi.

-

[12]

Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy . . . Facsimile, with Historical Notes by Karen Hess. 1805. Reprint. (Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, 1997), v.

-

[13]

Kevin J. Hayes, A Colonial Woman’s Bookshelf (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 80; Glasse, v-vi.

-

[14]

Meredith L. McGill, American Literature and the Culture of Reprinting, 1834-1853 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 1 and 5.

-

[15]

Mary Tolford Wilson, “Amelia Simmons Fills a Need: American Cookery, 1796,” William and Mary Quarterly 14, no. 1 (1957), 19.

-

[16]

Longone, Janice Bluestein. American Cookbooks and Wine Books, 1797-1950 : Being an Exhibition from the Collections of, and with Historical Notes (Ann Arbor, MI: Clements Library & the Wine and Food Library, 1984), 2.

-

[17]

Mrs. Isabella Beeton, Mrs. Beeton's Book of Household Management (London: S.O. Beeton, 1861).

-

[18]

Lydia Maria Child, The American Frugal Housewife (Boston: Carter and Hendee, 1832); Eliza Leslie, Seventy-five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes, and Sweetmeats (Boston: Munroe and Francis, 1832); Mrs. E.A. Phelps, Cookbook [1800?-1899?] Doc. 47 Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera. Winterthur Library, Winterthur, DE 19735; Fanny Kraemer, Recipe book, 1854-1886. Winterthur, Doc. 1394; Lydia Grofton Jarvis, Recipe book, [ca. 1840], Winterthur, Doc. 828.

-

[19]

Amelia Simmons, American Cookery, or the art of dressing viands, fish, poultry and vegetables . . . Adapted to this country, and all grades of life (Hartford, CT: Hudson and Goodwin, for the author, 1796), 36.

-

[20]

Ibid., 35.

-

[21]

Eliza Leslie, Directions for Cookery in its Various Branches (Philadelphia: E.L. Carey & A. hart, 1840), 7.

-

[22]

Leslie, Seventy-five Receipts, iv.

-

[23]

Driver, Culinary Landmarks, xxi.

-

[24]

The Cook Not Mad; or Rational Cookery: being a collection of original and selected receipts, embracing not only the art of curing various kinds of meats and vegetables for future use, but of cooking, in its general acceptation, to the taste, habits, and degree of luxury, prevalent with the Canadian Public (Kingston, U.C.: James Macfarlane, 1831); Driver, Culinary Landmarks, 274.

-

[25]

Ibid, iii.

-

[26]

Ibid.

-

[27]

The Cook Not Mad, or Rational Cookery; being a collection of original and selected receipts, embracing not only the art of curing various kinds of meats and vegetables for future use, but of cooking, in its general acceptation, to the taste, habits, and degrees of luxury, prevalent with the American publick, in town and country (Watertown, NY: Knowlton & Rice, 1831), iii.

-

[28]

Fiona Lucas and Mary F. Williamson, “Frolics with Food: The Frugal Housewife’s Manual by ‘A. B. of Grimsby,’” in Joan Nicks and Barry Keith, eds., Covering Niagara: Studies in Local Popular Culture (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2010), 150. The other major source for The Frugal Housewife’s Manual was Colin Mackenzie’s Five Thousand Receipts. First published in England in 1823 and republished in several American editions between 1829 and 1860.

-

[29]

Ibid, 164.

-

[30]

A. B. of Grimsby, The Frugal Housewife’s Manual: Containing a number of useful receipts, carefully selected, and well adapted to the use of families in general. To which are added plain and practical directions for the cultivation and management of some of the most useful culinary vegetables (Toronto: J.H. Lawrence, 1840), ii.

-

[31]

Maria Eliza Ketelby Rundell, A New System of Domestic Cookery (Boston: W. Andrews, 1807), Advertisement.

Appendices

Note biographique

Rachel A. Snell est doctorante en histoire à l’Université du Maine. Elle détient une maitrise en histoire des États-Unis de l’Université du New Hampshire depuis 2008. Sa thèse porte sur l’expérience quotidienne de la vie domestique pour les femmes de la classe moyenne du nord-est des États-Unis et du Canada anglais.

List of figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3