Résumés

Abstract

In less than a decade, the number of graduate schools of interpretation and translation in Korea has skyrocketed from one to a dozen. This is a reflection of the increasing interest in practical studies across the board, but in interpretation, in particular.

At such a juncture, it would be helpful to compare the entire process from entrance exams to curricula and finally the graduation exams to see whether the programs are the same or different and ultimately to proffer a “model” program that suits the current situation in Korea.

Four graduate schools were chosen for this study: Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, the oldest graduate school of its kind in Korea, Ewha Womans University, Seoul University of Foreign Studies and Sunmoon University, as a local representative.

Keywords/Mots-clés:

- curriculum,

- entrance exam,

- graduation exam,

- interpretation courses,

- translation courses

Résumé

En l’espace d’une décennie, le nombre d’écoles de traduction et d’interprétation a augmenté de façon fulgurante en Corée ; on compte actuellement douze écoles de traduction au programme de maîtrise. Ceci traduit l’intérêt croissant pour les études pratiques et en particulier pour l’interprétation.

Dans ce contexte, il serait utile de comparer et d’analyser le système de sélection (l’examen d’entrée), les cursus proposés (la composition des cours) et l’examen de sortie de ces écoles pour en trouver les points communs et les éléments de différence afin de proposer le cursus le plus adapté à la Corée.

Dans cette étude, nous avons retenu quatre écoles de traduction : l’école rattachée à l’Université Hankuk des études étrangères, l’école la plus ancienne en la matière en Corée ; l’école de l’Université féminine d’Ewha ; celle de l’Université de Séoul des études étrangères ; et enfin, celle de l’Université Sunmoon représentative de la province.

초록

최근 10년 사이 한국의 통역번역전문 교육 기관의 수는 13곳으로 증가했다. 이는 실용적 학문 전반, 그리고 특히 통역과 번역에 대한 관심이 증가하고 있음을 보여준다. 이러한 시점에서 각 대학원의 입학 시험, 교과 과정, 졸업 시험 등 제반 과정의 공통점과 차이점을 비교해 보고 통역번역 교육에 적합한 모델을 제시하는 것은 의미 있는 작업일 것이다.

본 연구는 가장 오랜 역사를 지닌 한국외국어대학교 통역번역대학원, 그리고 이화여자대학교 통역번역대학원, 서울외국어대학원대학교 통역번역대학원, 선문대학교 통역번역대학원 등 4개교를 표본으로 하여 시행되었다.

Corps de l’article

I. Introduction

The first graduate school of interpretation and translation in Korea, called the Graduate School of Simultaneous Interpretation, was established at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in 1979. At the time, there were many professors, even within the university, who doubted that simultaneous interpretation was possible between Occidental and Oriental languages. Despite the resistance from naysayers, the graduate school was launched with assistance from the government to allow students to spend the second of their three years of study in a foreign country to hone their linguistic skills and allow them to be exposed to foreign cultures. Up until 1996, when Ewha Womans University was allowed to set up its own graduate school of interpretation and translation, HUFS enjoyed a veritable monopoly for seventeen years, thanks for the most part to the Ministry of Education’s policy which limited the number of such educational institutions in Korea to one, since it is a small country without a large demand for interpretation at the conference level. Then in the mid-nineties, as the government eased various regulations related to institutions of higher learning, graduate schools of interpretation and translation began to be established across the country to currently number thirteen.[2] This can probably be considered a natural course of events when one considers the primordial importance of English in the overall curriculum of schools in Korea starting from elementary school all the way through to graduate school and even on the job market.

In addition to the degree programs offered at the graduate level, there are also numerous courses that are offered at the undergraduate level. A case in point, at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, students who majored in English used to have very few options: they could either major in literature or language (mainly linguistics). Now, the English department has been expanded to a full college, and students can also opt for an interpretation track. The overwhelming majority of students have, in fact, showed an interest in interpretation and so the college had no choice but to use the grade point average (GPA) to limit the number of students and determine who could major in interpretation. This is a trend that is noticeable across the world, since students prefer practical and pragmatic studies to the more esoteric ones. The courses at other universities range from just one or two courses to allow students to get a feel for interpretation/translation to a full-fledged program.

The purpose of this paper is to compare four graduate schools of interpretation and translation in Korea to understand what kind of programs are available and also to think about curriculum for interpretation and translation.

II. A Look at Curriculum in General

With such an explosion of interest in interpretation and translation studies, it is imperative to take a moment and consider what is being taught at these institutions, the framework of which is the curriculum. Is slapping together a few courses similar to those being taught at other institutions sufficient to constitute a curriculum? Is any thought given to the mission, purpose and overall objective of the program? In other disciplines as well, there sometimes exists a gap between what the scholars say should be done, and what the practitioners experience in the real world. “Scholars are asked to be relevant too, but are rarely expected to learn from practitioners. Practitioners are told to value the theories of academics, but they are rarely offered help in identifying and thinking about how their own theories shape and direct the decisions they make.” (ASCD yearbook, p.viii) This comment was made about curriculum in general, but the same could be said for interpretation and translation studies – probably more so. Ideally, in interpretation, more than in other areas, the gap between theory and practice should be kept at a minimum with practitioners providing input and participating in the formulation of theory, and theoreticians communicating with practitioners in order to base their theories on practice. More ideally, they should be one and the same so that there is no distance.

There are numerous definitions of curriculum. There are many scholars who look at curriculum as being a plan that is thought out and implemented by a school. Tyler (1957; p.79) stated that “the curriculum is all of the learning of students which is planned by and directed by the school to attain its educational goals.” Taba (1962, p.11) said succinctly that “a curriculum is a plan for learning.” Tanner and Tanner (1975: p.45) stated that “curriculum…is a plan that describes the necessary and insufficient ‘means’ for achieving particular learning ‘ends.’”

In contrast, Kaufman (1983; p. 54) stated that “curriculum is a means to an end. It should be judged as a means and changed accordingly.” Before the end can be decided, there has to be an understanding about what the goal is and where the institution stands at the present moment, that is to say, a needs assessment should be conducted to determine whether or not there is a gap and if one exists, the extent of that gap. Depending on the extent, each institution will be able to determine the curriculum in order to meet the ultimate goal. There are numerous needs assessment models which focus on different areas such as the pupil, the process, the program, school district planning or other areas (Kaufman, 1983; p.63-65), but ultimately the goal is to narrow the gap between where the institution should be or would like to be and where it is now. This may sound like a relatively straightforward beginning step, but even this first step might be difficult to take because those involved might have differing views of where they are and where they should be.

The second step involves planning. If the gap between the present and future is determined, a plan has to be devised to move from the present (where we are right now) and the future (where we would like to be.) To this end, “curriculum planners must decide what they wish to obtain as a result of planning” (Steller, 1983: p.70). Again, this might seem like a self-evident statement but if a needs assessment has not been conducted, it is basically the blind leading the blind because there is no clear-cut, defined objective. Furthermore, the defined objective should encompass, to a certain degree, what the future will be like for that institution. It is insufficient for the curriculum to cover the here and now. The optimum curriculum should be in a constant state of flux in order to be able to adapt to changes or even better to drive the improvements.

A generic model for curriculum planning shows that there are eight major stages with each stage interacting on an on-going basis with the other stages. In this generic model described by Steller (1983: p.82) most of the main points touched upon by other theorists are included. This model can be used to plan most any curriculum.

Figure 1

Generic model of curriculum planning

As with any generic model, the model is not tailor-made to fit a particular situation or institution, and as such, certain steps might, at times, seem to be inappropriate, redundant or even inadequate. However, this model when taken step by step, can be adapted to fit almost any circumstance.

Stage one is needed to define the goal or mission of the institution. Without a clear and succinct statement that is visible and clearly understood by all, the constituents of that institution will not have a grasp of the goal of the institution. A tacit understanding can be misleading, misconstrued or interpreted in different ways. In order to minimize the possibility of misinterpretation, it is important to spell out, in clear and simple language what the goal is. Stage two involves making an assessment of the current situation – where the program currently stands. It is only when an objective assessment has been made that one can determine where one wants to go. At times, the difficulty is not deciding what to do, but what not to do. There is so much that needs to be covered and taught – demands made by the students and by the clients – that keeping focus on the essentials can be difficult with all the distractions.

Stage three can be viewed as the stage at which the planners keep focus on what is most important for the program. Basically, the planners determine which needs are most critical and must be met. Following stage three, at stage four, the curriculum plan should spell out both long and short-range goals in a clear manner so that all those involved in the program can keep the goal in sight and adjust their instruction to that end and ensure that they do not veer off course.

Stage five is the equivalent of choosing the right path to reach the goal. There are many different roads or methods to reach an objective and the selection is not always made for the most rational reason. In not a few cases, the most strident opinion might be accepted or the most political which has unfortunate consequences.

Stage six consists of preparing the selected curricular alternative for implementation. A well thought-out action plan should also take into consideration various details in the plan – from the job title of the persons entrusted with each responsibility; the costs that will be incurred; the personnel, equipment, facilities and supplies that will be needed. Stage seven is the actual implementation which includes the pragmatic aspects of funding. If the funding is not available, the curriculum will look like an unattainable dream; and if the instructors are not trained in the competences required by the program, the plan will look like a lot of good ideas that cannot be implemented. The practical aspects of a plan can become impediments to the realization of the plan.

The last stage is monitoring, evaluating and recycling. No plan and certainly no curriculum can ever be picture perfect. Adjustments – minor and major – should be made on an on-going basis to ensure that the program does not get derailed. One of the difficulties in education is that the result or product cannot always be quantified or measured, unlike in business where the bottom line is there for all to see. Therefore, those who conduct the evaluation should be able to take a holistic approach and review both the tangible and intangible results of the curriculum and consequently make recommendations for improvements when necessary.

III. A Comparison of Curricula of Graduate Schools of Interpretation and Translation in Korea

3.1 Entrance Exams

Schools of interpretation and translation around the world use their unique entrance exams but a comparison of the exams show that there are nevertheless many areas in which they overlap, most notably regarding testing for language proficiency. Donovan (2003, p.32) found that the similarities of testing procedures are striking even though course design and applicant profiles are quite different.

To take the narrow view of curriculum to begin with, this section will compare the entrance exams, courses and graduation exams of four universities in Korea which have a graduate program in interpretation and translation. They are the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, the oldest graduate school of its kind, Ewha Womans University, Seoul University of Foreign Studies, the most recent addition, and Sunmoon University, as representative of local universities. In the case of GSIT HUFS, the entrance exam has, traditionally, been held on the first and second Saturdays of November.[3] The first round of exams is held on the first Saturday and only those students who pass the first round are qualified to present themselves for the second round held the following week. Though there are some fluctuations year-on-year, usually about 10% or so of the applicants for the Korean-English department are accepted for the first round; and about half of the applicants for the second round. For example in 2004, there were almost 900 applicants for the first round; about 100 students passed the first round and presented themselves for the second round. In view of the large number of applicants, the first round consists of a multiple choice exam, and the second round of a written exam composed of translation and essay writing and an oral exam in which applicants are asked to summarize from English into Korean and vice versa.

Ewha Womans University is the only graduate school in Korea that makes the clear distinction between interpretation and translation right from the entrance exam. Here, the first round consists of writing an essay in the foreign language and summarizing texts. Those who pass the first round may present themselves for the second round which consists of an oral exam, mainly summary exercises in both directions, for the interpretation candidates and a written exam for the translation students. When it was first established, Ewha had a special screening which exempts students from taking the entrance exam, but starting from last year, this system has been scrapped.

Seoul University of Foreign Studies is the latest addition to the pool of educational institutions which teach interpretation and translation to have graduated students. It conducts a special screening and those students who have completed one or more primary/elementary, junior high or high school programs in a foreign country or have studied for more than three years in a foreign country are exempt from taking the entrance exam. In those cases, the first round does not consist of an exam, but a screening of the application documents, and an in-depth oral exam. Those students who are not qualified for the special screening must sit for a Korean exam and an exam in their foreign language; and a second exam which consists of translation and writing in their foreign language followed by an in-depth oral exam, comprised of current events questions in the foreign language and consecutive interpretation exercises in both directions.

Sunmoon University also has a two-pronged system. The first prong consists of two exams – the first a listening and translation exam, followed by an interview and interpretation exam; the second prong, a listening comprehension exam in the relevant foreign language and a Korean listening exam; followed by a translation exam and interview/interpretation exam.

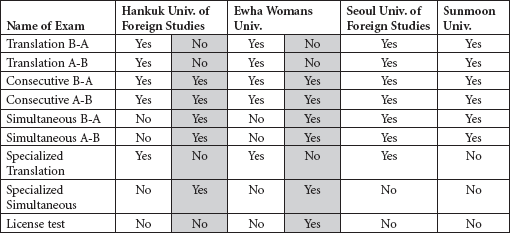

Table 1

Entrance exams for graduate schools of interpretation and translation

All four graduate schools have broken down their entrance exam into two phases, with only those students who have successfully passed the first phase, being eligible to present themselves for the second phase. All institutions have some form of written and oral tests, with some consisting of just translation while others also including summarizing. The special screening is a way that educational institutions attract students – sometimes competent, sometimes less so – who are hesitant about taking exams and yet meet the basic requirements of the institution.

3.2 The Courses

The graduate schools included in this study have some overlapping courses which constitute the foundation of any program teaching interpretation and translation as well as other courses that are unique to the program and which aim to meet the needs of the students (Appendix 1). A case in point, all the programs have a course entitled ‘Introduction to Interpretation/Translation.’ The methodology and content will vary among programs depending on the instructor, but the idea that an introductory course is necessary is the same. The same is true for the advanced B language courses. Though such courses with a focus on improving B language skills might seem like an anomaly in a graduate school program, it is necessary to have such courses because not all students have resided in countries of their foreign language – a prerequisite in many Western graduate schools of interpretation.[4] Since language and consequently interpretation and translation encompass culture and subject matter as well, there are often courses such as culture, regional studies, intercultural communication which aim to provide general information about and shed light on extralinguistic factors which can be baffling for someone who has had minimal exposure to foreign cultures. The Korean language courses are quite useful because they look at the language from a different perspective, that is, as a communication medium. In the case of Korean, there are several levels to the language and honorific forms which can be confusing. Using a lower register can be insulting, while using an overly high register can be awkward, or even worse, comic.

In the case of Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, the student body can be divided into those students who have lived abroad for many years and others who have had minimal exposure to foreign cultures. Students in the first category take the Korean class while students in the second take the ‘B’ language courses which cover public speaking, writing and culture. The foundation courses are followed by more specialized courses. During the first semester, for example, students take general translation courses in order to learn the basics of translation. Then, starting from the second semester, the courses become more specialized and there are courses in ‘Translation of Economic and Commercial Texts’ and in the third semester, ‘Translation of Scientific and Technical Texts.’

In contrast, Ewha Womans University places great emphasis on basic and general courses so that students can have a sturdy foundation on which to build their skills. For example, they offer advanced B language (Korean) for native speakers of other languages, advanced B language (for Koreans), Advanced Korean, British and American Culture for French, Chinese and Japanese majors, Economics, Science and Technology, Regional Studies and Advanced English in addition to the interpretation and translation courses. Seoul University of Foreign Studies and Sunmoon University appear to give students a general overview of interpretation and translation. SUFS offers A and B language courses, in addition to the interpretation and translation courses, while Sunmoon University provides courses in B language debate and social and cultural issues of B language courses.

3.3 Graduation Exam

The last phase of the program is the graduation exam – a nerve-wracking experience for any student, but even more so for students of interpretation and translation since these exams are notorious for being difficult to pass. The difference between the four institutions is that SUFS and Sunmoon do not separate interpretation and translation while HUFS and Ewha do. SUFS and Sunmoon require students to take translation, consecutive and interpretation exams, in both directions, but the texts are general rather than specialized ones. After the results of the exam are tallied, the students determine their major or concentration area. Those having scored higher grades in interpretation, graduate with a major in interpretation and minor in translation; and vice versa for those who scored higher in translation. HUFS separates students into two tracks after the first year of studies, namely, translation and consecutive interpretation and conference interpretation. Ewha separates students from the start, hence the different line-up of exams from institution to institution. Though it is often considered an aberration in Western schools to mix interpretation and translation, in Korea there are those who argue in favor of offering the same curriculum across the board or at least having a portion of the curriculum overlap. It is not unusual for in-house interpreters to be expected to do simultaneous, consecutive and translation work in both directions! The distinction between the two competences has not been clearly defined so that a person who is trained to do one is expected to also be capable of doing the other as well. Therefore, separating the two curricula completely has, at times, been considered disadvantageous for students after they graduate.

If a student fails to pass the graduation exam on his/her first try, HUFS and Ewha limit the number of attempts to four times (though Ewha limits the attempts for the interpretation license to three times[5]); SUFS to three times and Sunmoon does not indicate whether there is a limit.

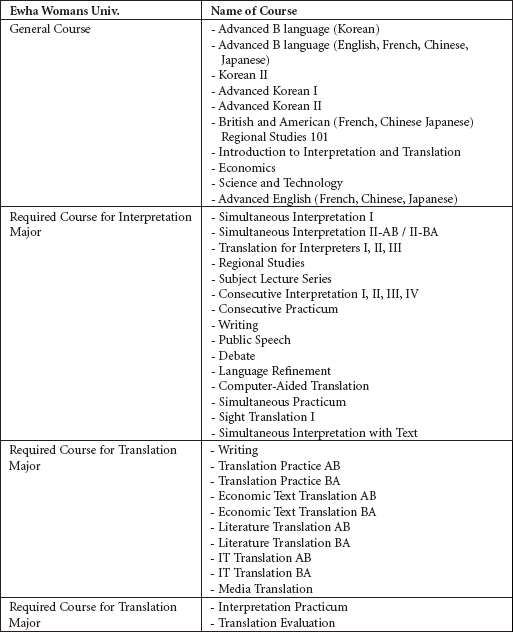

Table 2

Graduation Exams

The shaded areas depict the two different tracks that are offered at the graduate schools of HUFS and Ewha. For HUFS, the first column covers those students who focus on translation and consecutive interpretation, and the second the conference interpretation track meaning those who do consecutive and simultaneous interpretation. For Ewha, the first column is for translation students and the second for interpretation students.

IV. Evaluation of the Curriculum

Articles and entire books have been written about curriculum evaluation and therefore a few paragraphs about curriculum evaluation in this article cannot begin to do justice to it. However, including a section on curriculum evaluation is a necessary step to bring closure to the entire process of comparing curricula of graduate schools of interpretation and translation in Korea. This is a phase that is often neglected due to ignorance, negligence or indifference. However, to ensure that a curriculum is effective – for whichever program – it is a crucial last step.

In translation studies, a lot of research has been conducted on quality assessment or evaluation (Bowker, 2000; Kussmaul, 1995; Lauscher, 2000; Larose, 1998; Schäffner, 1998). But in most cases the evaluation is focused on the student performance – whether it is a translation, consecutive interpretation or simultaneous interpretation – and determining whether something could be done to improve it. However, there are few, if any, articles that look at the curriculum of an interpretation/translation program to evaluate or determine its effectiveness. When one considers that curriculum evaluation is conducted in almost all other areas of studies, one may wonder why it is not for interpretation and translation studies.

The yardstick that is often used in educational circles to determine the worthiness of a curriculum is the Tyler Rationale which consists of four questions which curriculum developers should use when devising a curriculum.

Walker and Soltis 1992: 56

What educational purposes should the school seek to attain?

What educational experiences can be provided that are likely to attain these purposes?

How can these educational experiences be effectively organized?

How can we determine whether these purposes are being attained?

Though Tyler recommends that they be used to devise the curriculum, they can also be used as a post-implementation yardstick to determine the extent that the goals have been met. To answer question one, before the beginning of the program, the school has a main educational purpose in mind. Since interpretation and translation programs are very practical, the conventional wisdom is that the yardstick to measure the success of such a program is the employment rate – how many students have found permanent or semi-permanent positions or are working actively as freelancers. For question two, did the school provide the appropriate educational experiences to attain the purposes of the school? Since all the instructors at the various graduate schools were almost all trained at HUFS, the teaching methodology is more or less the same, depending on when they were trained and by whom. Most of the interpretation and translation is conducted in-class with very little, if any, actual hands-on training. One area that all graduate schools could improve on is internships or hands-on experience. The difficulty is that there are no international organizations that are based in Korea, let alone Seoul, and it is therefore difficult to predict when international conferences will be held and whether for example, dummy booths would be allowed.

Question three is, were the educational experiences effectively organized so that the students could benefit the most? In all of the four institutions in question, the first year consisted mainly of foundation courses and interpretation and/or translation courses that advanced in difficulty into the second year. And the last question was, is there a way to determine whether the purposes have been attained? After the program has been implemented, the school must determine whether the school has attained those goals. The answer to this question would probably revert to the first question which is to see how many graduates find jobs.

The Tyler Rationale is, in fact, a measure that can be used to bring to the surface and clarify the mission of the school. At times, there is a vague and general understanding of the mission of the school, but without a verbalization of those thoughts, the members of the team might be pulling in different directions. For example, not all graduate schools of interpretation and translation, seemingly schools of the same nature, will, necessarily, have the same purpose. One institution might be aiming solely for top-of-the-line conference interpreters and specialized translators, while another institution might be looking at the whole range of interpreters including liaison interpreters. If the instructors are not all in agreement, the students might have to suffer through difficult times because the expectations of the teachers will be so high. With the proliferation of graduate schools of interpretation and translation, it would behoove newcomers to consider finding and building a niche in interpretation and translation in order to differentiate themselves from the other institutions.

V. A Proposal

After comparing the curricula of four graduate schools of interpretation and translation in Korea, the question that follows is: Is there an ideal curriculum that suits the environment of Korea? If so, what is it?

In view of the circumstances in Korea, one option that is feasible is a three-track system: one track for translation (T), another for consecutive interpretation and translation (CI&T) and the third for conference interpretation (CI), much along the lines of the Monterey system. One weakness in the current curricula that is offered at most schools is that there is very little flexibility in the courses that students can select. With the three-track system, students would naturally focus on their majors, but there should also be the option to take electives in other tracks. For example, a student in the translation track should be allowed (or even required) to take consecutive interpretation classes, and students in CI&T should be allowed to take a simultaneous interpretation class; and CI students, translation classes. Since interpretation and translation supplement and complement each other, such a system would allow students to experience different forms of interpretation and translation while keeping a focus on their majors. Some electives that could be offered are basic courses in economics, political science, government, IT, desktop publishing etc. but with a definite bent for interpreters. They should not be simple introductory courses but rather courses that focus on ideas and concepts that will most probably surface during interpretation and translation.

In addition, students, if they so wish, should be allowed to change their majors (by taking an exam or through any other means that the faculty feels fit). Most students come to such institutions in order to become conference interpreters. However, in most cases, they have only a vague (if even that) idea of what the job entails. Once they realize the pressures and criteria that must be met in order to become a conference interpreter, some students might decide that that is not for them. The reverse can also be true. A student might have wanted to major in translation but after dabbling a little bit in consecutive, finds that interpretation is exciting. In both cases, the students should be allowed to change their majors. The key to an ideal curriculum is to allow for flexibility so that the students can choose those courses that are most appropriate for the individual student.

Another option is to change the current two-year system to a three-year system. There is a general consensus that two years is not enough for students to reach the high level needed to become a conference interpreter and those students who have had less exposure to foreign languages and culture might take a little more time to obtain a degree of facility with the language. In such cases, allowing for late-bloomers to fulfill their potential is, from an educational perspective, very encouraging for students. Furthermore, in many cases, students end up investing at least three years in their studies because not many of them manage to graduate on their first try. As such, making the three-year period official would also allow them to take classes.

VI. Conclusion

The purpose of this article is to provide an overview and comparison of four representative graduate schools of interpretation and translation in Korea. The Graduate School of Interpretation and Translation at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies is the oldest, followed by Ewha Womans University which separates interpretation and translation from the start, and Sunmoon University as the local representative and the most recent addition, Seoul University of Foreign Studies. Since the instructors are almost all former alumna of HUFS, the curricula of these four institutions are more or less similar with slight variations.

All the graduate schools concentrate on practical training courses, but the extent to which they are broken down into subcategories, for example, general translation, followed by economic, technical etc. fluctuates between institution. One area which is unclear is the extent to which technology is used in the classroom. Since the Internet is so widespread in Korea, the Internet could be used in translation classes to allow students to access the Internet to find information that they need to translate a text – a move that is almost second nature for a translator when translating a text. For interpretation, the use of Powerpoint when giving a presentation has become so widespread that it is almost unusual to meet a speaker who speaks without visuals. Incorporating Powerpoint presentations in the curriculum would also be helpful for students after they graduate.

One worrisome trend is the increasing number of graduate schools of interpretation and translation. At last count, there were twelve and another one is to be established this year. As in any area or discipline, competition can stimulate and improve quality. However, in the process the market could be flooded with unqualified interpreters/translators which leads to chaos and disorder. Ultimately, after a proliferation of such institutions, there is bound to be a period of adjustment after which calm will be restored.

Parties annexes

Annexe

Appendix 1

Comparison of Courses Offered

Hankuk University of Foreign Studies

Ewha Womans University

Seoul University of Foreign Studies

Sunmoon University

Biography

Hyang-Ok Lim

Prof. Lim is currently professor at the Graduate School of Interpretation and Translation, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, and also a freelance conference interpreter and translator. She graduated from E.S.I.T. and holds an Ed.D. (Illinois State University) and her main areas of interest are teaching interpretation and translation. She is a member of AIIC since 1996.

Notes

-

[1]

This work was supported by Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Research Fund of 2006.

-

[2]

To list the universities to which the graduate schools are affiliated, they are: Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Ewha Womans University, Handong Global University, Cheju National University, Sunmoon University, Seoul University of Foreign Studies, Pusan University of Foreign Studies, Sungkyunkwan University, Korea University, Kyemyung University, Dongguk University, Bethesda University and Joongang University.

-

[3]

The academic year in Korea starts in March.

-

[4]

It was not until the mid-1980s that foreign travel was deregulated for Koreans. Before the deregulation, travel abroad was limited to diplomats, businessmen and others on official business. Consequently, exposure to foreign cultures was extremely limited, especially since this was before the Internet era.

-

[5]

Since Ewha separates the students from the beginning of the program, the interpretation section is quite large and not all the students reach the conference interpretation level. To differentiate the top students, an additional tier has been added – something that only Ewha has done. Even if students pass the interpretation exam, in order to be considered conference interpreters, they must also pass the interpretation license exam.

References

- Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development Current (1985): Thought on Curriculum: 1985 ASCD Yearbook, Alexandria, Author.

- Bowker, L. (2000): “A Corpus-Based Approach to Evaluating Student Translations”, The Translator 6-2, p. 183-210.

- Donovan, C. (2003): “Entrance Exam Testing for Conference Interpretation Courses: How important is it?”, Forum 1-2, p. 17-46.

- Kaufman, R. A. (1983): “Needs Assessment”, In F. W. English (Ed.), Fundamental Curriculum Decisions: 1983 ASCD Yearbook, Alexandria, Jarboe.

- Kussmaul, P. (1995): Training the Translator, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, John Benjamins.

- Larose, R. (1998): « Méthodologie de l’évaluation des traductions », Meta 43-2, p. 163-186.

- Lauscher, S. (2000): “Translation Quality Assessment: Where Can Theory and Practice Meet?”, The Translator 6-2, p. 149-168.

- Schäffner, C. (1998): Translation and Quality, Great Britain, Short Run.

- Steller, A. W. (1983): “Curriculum Planning”, In F. W. English (Ed.), Fundamental Curriculum Decisions: 1983 ASCD Yearbook, Alexandria, Jarboe Printing.

- Taba, H. (1962): Curriculum Development: Theory and Practice, New York, Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

- Tanner, D. and L. Tanner (1975): Curriculum Development: Theory into Practice, New York, Macmillan.

- Tyler, R. (1957): “The Curriculum Then and Now”, Proceedings of the 1956 Conference on Testing Problems, Princeton, Educational Testing Service.

- Walker, D. F. and J.F. Soltis (1992): Curriculum and Aims, New York, Columbia University.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Generic model of curriculum planning

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Entrance exams for graduate schools of interpretation and translation

Table 2

Graduation Exams

Hankuk University of Foreign Studies

Ewha Womans University

Seoul University of Foreign Studies

Sunmoon University

10.7202/003410ar

10.7202/003410ar