Résumés

Abstract

This article focuses on paratextuality in the realm of dubbing drawing on the author’s professional experience as an audiovisual translator in Catalonia. After a brief discussion of the theoretical approach to paratextuality and the notion of audiovisual text, the article lists the main paratextual components in dubbing and describes how they are dealt with by audiovisual translators. The article focuses on fiction films, cartoons and television series, be they for cinema, television, Internet or DVD, and considers paratexts at two levels: in the audiovisual text itself and in the written synchronised translation.

Keywords:

- audiovisual text,

- paratext,

- dubbing,

- television,

- film

Résumé

Le présent article traite de la paratextualité dans le domaine du doublage. L’auteure fait appel à son expérience professionnelle de traductrice audiovisuelle en Catalogne. Après un bref bilan théorique sur la paratextualité et la notion de texte audiovisuel, l’article énumère les principaux éléments paratextuels dans le doublage et décrit comment ils sont traités par des traducteurs audiovisuels. Sont pris en compte des films de fiction, des dessins animés et des séries, que ce soit pour le cinéma, la télévision, Internet ou un DVD. Les paratextes sont analysés sous deux angles : dans le texte audiovisuel proprement dit et dans la traduction écrite synchronisée.

Mots-clés :

- texte audiovisuel,

- paratexte,

- doublage,

- télévision,

- film

Corps de l’article

Paratextuality is considered by Genette (1997) as one of the five key elements in his theory of transtextuality next to intertextuality, metatextuality, hypertextuality, and architextuality. This article will focus on paratextuality in the realm of dubbing. After a brief discussion of the theoretical approach to the topic, in which key notions related to paratextuality and audiovisual text are presented, the article outlines the challenges to audiovisual translators that are introduced by paratextual elements and describes how they are dealt with. It must be stressed that while the article has been inspired by the bibliographical references quoted in the text, it draws mainly on the author’s own experience as an audiovisual translator in Catalonia and should be considered as a first step towards a wider investigation which would include a wider corpus and would take into account other practices.

1. Paratextuality and the audiovisual text: an overview

In the field of Literary Theory, paratexts comprise those elements which accompany the text, either within it or outside it (Genette 1997), and can be classified within two broad categories: peritexts, which are paratexts within the same book, and epitexts, which are paratexts outside the book. Genette presents an extensive lists of peritextual features, which include: publisher’s peritext (including the outermost peritext, i.e., cover, title page, and appendixes, and the book’s material construction, i.e., selection of format, selection of paper, typesetting), name of the author, title and subtitle, please-inserts, dedications and inscriptions, epigraphs, prefaces, intertitles, notes, public epitexts (such as newspapers, magazines, lectures, etc.), and private epitexts (such as correspondence, diaries, oral confidences, etc.).

These categories apply to the written literary text, but Genette’s taxonomy can be extended to the field of film and television studies, as pointed out by Metz (1994) and Stam (2000). This is in fact what authors such as Gray (2010), Kreimeier and Stanitzek (2004), Stanitzek (2005) or Böhnke (2007) have done. From this perspective, the elements included under the umbrella of paratexts are as varied as titles, logos, trailers, teasers, appetizers, credits, intertitles, authors, formatting issues, and all types of promotional material, among other features.

My focus in this article lies in paratexts in dubbing within the framework of Audiovisual Translation Studies (AVTS). To the best of the author’s knowledge, a systematic description of paratexts found in the translation of audiovisual texts is not yet available. This paper aims to partially fill this void by focusing on dubbing and pointing to how translators face the various paratexts linked to the audiovisual text. In order to do so, the scope of the term ‘text’ has to be broadened so that it includes the audiovisual text, whichever medium is used to exhibit or broadcast it (cinema, television, computer, etc.). Before moving into the audiovisual domain, a brief approach to the concept of ‘text’ should be presented.

The concept of text has traditionally been linked to the written word (Cary 1960), but authors such as Delabastita (1989), Nedergaard-Larsen (1993), Lambert and Delabastita (1996), Zabalbeascoa (1997, 2001, 2005a, 2005b), Gottlieb (2000), and Chaume (2003, 2004) have broadened this concept to include audiovisual productions and have emphasised the notion of communication as a defining trait of texts. It is considered that audiovisual texts reach the audience by means of two channels (acoustic and visual), which include elements both verbal and non-verbal in nature. Therefore, four basic components must be considered in audiovisual texts: words that are heard (audio + verbal), words that are written (visual + verbal), music and special effects (audio + non-verbal) and images (visual + non-verbal). Following Chaume (2003: 90), various other issues must be taken into account to provide a general picture of the audiovisual text: the channel (visual/acoustic), the codes used in the filmic meaning-making (linguistic, paralinguistic, musical, special effects, iconic, etc.), and the medium (TV, cinema, computers, etc.).

For the purposes of this article, I will focus on audiovisual texts – meaning texts with a visual and an acoustic component – which are generally translated for dubbing purposes. These include filmic texts, be they for cinema, television or DVD, and televisual texts (series and cartoons of various types), generally released on television but which can also be broadcast via the Internet and found on DVDs. Non-fiction films, which are generally re-voiced by means of a voice-over, and subtitled programmes will not be taken into account.

2. The translator’s role in the dubbing process

Dubbing an audiovisual text from a source language into a target language is a complex process where intermediate texts and various agents are involved. It is therefore important to grasp the complexity of this process before analysing the paratexts.

As put forward by Matamala (2010), various professionals such as project managers, translators, dialogue writers, linguists, artistic directors and dubbing actors participate in the dubbing process. Generally speaking, the translator is contacted by a project manager and they agree on the working terms and conditions as well as the deadlines. The translator is then sent a digital audiovisual copy of the audiovisual product plus a script or transcript, if available. The translator’s role is to produce a written translation of the audiovisual text which will include, at the very least, all the linguistic elements of an acoustic nature and, generally, the most relevant linguistic elements of a visual (i.e., written) nature. The next step is the production of a synchronised version in which the dubbed dialogues are crafted so that they approximately match the lip movements of the characters (lip synchrony) and coincide more or less in length with the original version (isochrony) while taking into account the characters’ movements (kinetic synchrony). This task can be either assigned to the dialogue writer or to the translator. This written version will include a series of pre-established dubbing symbols to help the work of both the dubbing actors and the sound technician. Next, this written text is cut into takes of a certain number of lines, and time codes are included. Finally, certain clients require a linguist to check the written version and correct the linguistic features that do not conform to the client’s style sheet. Linguists might also include useful remarks for the voicing actor, mainly concerning pronunciation issues. The result at this stage is a written script in the target language, with symbols for both actors and sound engineers, ready for the actual recording studio.

Once recorded, clients might require a linguist to revise the recorded version and they might ask for retakes if necessary; in other words, they can ask for a specific take to be recorded again. The process finishes with the final mixing by sound engineers, the viewing by the artistic director and the acceptance of the product by the client or client’s representative, who might ask for further retakes if they are not satisfied with the result.

Many factors can alter this established path: for example, when working with blockbuster cinema releases, translators sometimes have to work with preliminary versions and translate multiple versions of the same film without knowing the actual ending of the film until the very last minute.

For the purposes of this article, I will focus on the paratextual elements that can be found at two different stages of the process of dubbing: on the one hand, the paratexts found in the audiovisual text itself; and on the other hand, the paratexts added to the written text as generated by the translator/dialogue writer/linguist to facilitate the process of dubbing and recording.

3. Paratextual elements in dubbing: the audiovisual text

In dubbing two audiovisual texts have to be considered: the original and the dubbed audiovisual texts. Some of the paratexts included in the original find their way into the target language version, but there are also paratextual elements that are only related either to the original or to the dubbed version. A list of paratexts found in filmic audiovisual texts is the following:

Peritext: opening/end credits (which generally include title, logos, authors and sometimes also subtitles, dedications), post-credit sequences, cold opens or teasers, bonus materials (director’s commentaries, interviews, etc.), and script.

Epitext: film posters, trailers, promos, dedicated websites, press releases, DVD covers and all types of hype and synergy.

3.1. Peritextual features in the audiovisual text

In this section I will analyse the main peritextual elements in the original audiovisual texts, and I will point out their specificities within the audiovisual text and the role of the translator in delivering these elements in the dubbed version. I will focus on: opening credits, end credits, post-credit sequences, teasers, bonus materials and DVD features, and scripts.

3.1.1. Opening credits

Film credits have been the subject of an increasing amount of research (see Mourgues 1994) and have been considered from various points of view: (a) as having an economic and contractual function; (b) as an object of study within a broader history of design, and (c) as a paratextual element which organizes “the spectator’s passage from an extratextual to a textual world” (Straw 2010: 159). Focusing specifically on the opening credits, they constitute a “complex intermediary zone” that introduces the main film by means of typesetting, images and songs (Stanitzek 2005: 37; 2009). All these elements create the traditional title sequence, a sequence which has disappeared in some films – for example, the title of Batman Begins (Christopher Nolan, 2005) is displayed at the end of the movie – or which coexists with the opening scene in other films – for example, in Finding Neverland (Marc Forster, 2003) credits are superimposed over the action.

What interests the audiovisual translator are the linguistic and paralinguistic elements which can be conveyed in the target language, be it of an oral or written nature. These elements may include: (a) superimposed written texts depicting the title, subtitle, authors (major actors and crew), logos, and dedications, (b) songs with lyrics in the source language, and (c) incidental speech or paralinguistic features. Needless to say that if action begins during the film credits – in other words, if the opening scene coincides with the opening credits – and film dialogues are heard, the translator will have to render them in the target language.

3.1.1.1. Opening credits: Superimposed written texts

Superimposed written texts include title and subtitle, authors (major actors and crew), logos, and dedications. Each of these features will be further described next.

Title and subtitle are “paratextually integrated into the opening credits, an essential element of film enunciation” (Stanitzek 2005:37). The film title’s functions, according to Kolstrup (1996), are: identifying the film, guiding us through the TV flow or the film pages of newspapers/magazines, informing our interpretation/reception of the film, and promoting the film. Many authors have analysed the translation of titles in audiovisual media (Díaz-Cintas 2003; Díaz Teijo 1997; Fuentes Luque 1998; González Ruiz 2000; Martí and Zapater 1993; Serrano Fernández 2001; Peng 2007; Yin 2009) and have highlighted the different issues at stake when translating a title, such as the effects of censorship at certain historical moments or the influence of commercially-based strategies. Needless to say, translating a title is not an easy task: it has to be meaningful and it has to be catchy. However, this complex process can be a wasted effort because translators can propose titles (and subtitles) but the final decision is not theirs to make.

Taking, for example, the 49 films dubbed into Catalan by the Catalan Television TVC in 2008, 24% have a title which has been freely translated from English. Most films in Catalonia are first released in Spanish and, when the Catalan version is released, for marketing purposes the general norm is to provide a Catalan translation of the Spanish title – not the original one. This is why Miss Pettigrew lives for a day (Bharat Nalluri, 2008) becomes Un gran dia per elles [A great day for them] or Made of honour (Paul Weilend, 2008) is rendered as La boda de la meva nòvia [My girlfriend’s wedding], both literal translations of their Spanish counterparts.

Credits also include a list of production and cast members: the opening credits generally include the most important members of the production, whilst an extensive list is included at the end of the film. This paratextual text is kept as in the original and is not changed in the target language because proper names are easily recognisable by the target language viewer.

Apart from the title and the production and cast members, logos are also part of the opening credits but they do not normally pose problems to audiovisual translators. They generally contain graphical elements (a mountain, a man on a moon, a lion, etc.) plus the name of the studio (Paramount, Dreamworks, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Columbia, etc.), hence no information needs to be translated: they are kept as they are in the original version in the dubbed product.

Finally, some films may contain a dedication between the opening titles and the actual filmic text, and also sometimes before the end credits. These dedications can be either transferred by means of a diasemiotic voice-over – that is, an off-screen narrator that reads the translation of the dedication whilst the text is shown on screen – or by means of a caption. However, it is often the case that they remain untranslated.

3.1.1.2. Opening credits: Songs with lyrics

Apart from written texts, opening credits can coexist with songs with lyrics which can be relevant in terms of meaning-making. Depending on the client’s criteria, the country’s tradition and the importance of the song, it will be decided whether to translate it or not, be it by means of subtitles or a new dubbed version. For example, the main title theme song for the TV show Rescue Me is a shortened version of C’mon C’mon by the Von Bondies and, as is generally done in this type of product, the lyrics are not translated in the dubbed Catalan version despite its meaning. A different approach is adopted towards cartoons addressed to a young audience, where the main title theme song is generally dubbed into the target language. A specialised audiovisual translator is usually in charge of this task, which not only requires a correct understanding of the original – a transcript is often not available – and the obvious competences of an audiovisual translator, but also a thorough knowledge of music to deliver a song which conforms to the rhythm and rhyme of the original. Some studios prefer to ask the audiovisual translator for a rough translation of the song lyrics and then commission the song adaptation to a specialised musician.

3.1.1.3. Opening credits: Incidental speech

In certain films, the opening credits coexist with some action in which incidental speech or paralinguistic features such as laughter, coughs, sneezes or unintelligible dialogues (ad libs) are heard. The job of the dialogue writer is to include all these features in the script by means of the appropriate symbols and propose a translation for all the ad libs, i.e., impromptu unscripted dialogue, which is then dubbed in the target language version.

3.1.2. End credits

In some older films, end credits often only consisted of a title simply stating The End, but nowadays they usually present an extensive list of superimposed written texts depicting all the crew involved in the film (name plus role), scrolling bottom-to-top or right-to-left. This information is generally deemed not relevant to the translation process and only in some specific products are translators asked to render all this information in the target language, generally when the original product will be incorporated in a home production and credits will be changed.

Songs and outtake sequences can coexist with end credits: songs at this point are dealt with in a similar manner as songs in the opening credits (see 3.1.1.2). As for the outtake sequences, also called bloopers in TV jargon, they are always dubbed in the target language version and the main challenge is to transmit the same comical effect. For instance, many Jackie Chan films include outtakes over the closing credits, which have become a kind of trademark. The American sitcom Fresh Prince of Bel Air also included outtakes over the closing credits, and a more recent example is Pixar’s computer-animated film Toy Story 2, where the outtakes were created for the purpose of providing audience enjoyment. Sometimes outtake sequences belong to a post-credit sequence, a paratextual feature that will be described in the next sub-section.

3.1.3. Post-credit sequences and teasers

Before the opening credits and after the end credits, special sequences can be found: these are teasers (or cold opens) and post-credits sequences, respectively. Post-credit scenes generally include a short clip about a sequel or a following episode in the series in order to attract the audience’s attention. Broadcasters sometimes also adopt the so-called hot switch, meaning that one TV show follows the previous one without a commercial break and thereby engage the audience by means of a cold open. Cold opens, also called teasers, are sequences which can fulfil at least the following two functions: to produce a summary of previous episodes in television series or film sequels, or to offer an initial sequence which will have a meaning in the subsequent story line (a flashback or a flash-forward, for instance).

Both post-credit sequences and teasers are dubbed in the target language version following the standard procedure and the main problem posed to translators is the lack of contextual information to fully understand the sequence. For instance, if teasers include a summary of previous episodes, it might well be that these previous episodes have been translated by another professional translator. The lack of information and, very often, the lack of a written transcript, make it more difficult to understand and translate these excerpts, although modern web-based communication tools enable easy communication between all of the professionals involved in this area. The presence of an uncontextualised flashback or flash-forward can also complicate the task of the translator, especially in a television series which has not been fully released and, therefore, detailed information is not yet available on the net.

3.1.4. Bonus materials and DVD features

Epitextual materials of a different nature are to be found in DVD releases. In the case of DVDs, the audiovisual text is not presented in isolation but instead, comes accompanied by a variety of features: ‘the making of’ documentaries, interviews, film scenes which have not been included in the final version, behind-the-scenes footage, outtakes, alternative endings, extended versions, storyboards, video-clips, trailers, director’s commentaries, scenes with special effects, etc. Bonus materials are generally translated by a different translator by means of subtitling and voice-over (for interviews), even if the film has been dubbed. When working with the majority of these features the translator is not given a transcript and this fact coupled with the large amount of incidental speech and background noise adds to the challenge of understanding the original. Moreover, since the film has generally been translated by another audiovisual translator and not by the professional translating the bonus material, the lack of contextual information can be problematic.

3.1.5. Scripts

In addition to the previously discussed elements, some authors consider the written script to be a paratextual component of the actual audiovisual product (Bruno 1993: 364). The script that is received by the translator – if any – can be of a varying nature:

Pre-production scripts can omit certain scenes and include scenes eliminated from the broadcast version, hence forcing translators to rely on their oral comprehension skills;

-

Post-production scripts are created from the final broadcast version. These encompass:

dialogue lists or transcripts especially made for dubbing purposes: of uneven quality, they generally contain a faithful translation of the dialogues, hence translators do not have to memorise the text while translating and can rely on the written script once they have checked that it is correct;

combined continuities, including dialogue transcript and description of visuals, which work in a similar way to dialogue lists but can also help the translator with additional information about the setting, time, etc.;

spotting lists, i.e., spotted subtitles in the original language, which can only be used for reference purposes because they do not contain all the dialogue of the film, which the translator will need to convey in the dubbed version, and

combined continuity and spotting lists, i.e., a combination of the two previous scripts. This is generally the most thorough type of script and sometimes includes notes explaining specific terms or difficult expressions for the translators’ reference.

The quality of scripts can be uneven and incorrect transcriptions, which can confuse the translator, are sometimes found (see, for instance, the examples presented by Matamala (2009), including medullamagada instead of medulla oblongata and defence centre instead of reference centre). Translation scenarios can be quite complex: it is not uncommon, especially when dealing with languages other than English, for the translators to be provided with an international script which is an English translation of the original audiovisual product. Working on a Japanese production with a written English script, where part of the text has not been correctly conveyed, is a real example of a difficult scenario that made the translation task challenging, even more so as the translator involved was not familiar with Japanese.

In conclusion, this section has presented many paratextual features found in the original version and has described how they are rendered in the final dubbed version. However, paradoxically, it is worth stressing that some specific peritextual features which are not found in the original text are sometimes present in the dubbed version. This is the case for the names and roles of the main agents in the dubbing process, as those individuals could be considered as added authors and crew members. Translator, dialogue writer, dubbing director, main dubbing actors/actresses and dubbing studio are included as an addendum to the original film credits. When released in theatres, they are generally incorporated as added paratextual features that appear at the very end of the film – at which point the majority of the audience has generally left the theatre. From the DVDs perspective they are sometimes included in the bonus material section, but on television they generally remain invisible.

3.2. Epitextual features in the audiovisual text

The types of epitextual elements linked to the audiovisual texts are varied but their most common function is to promote the actual cinema or TV show. The so-called hype and synergy include the following products:

posters on subways, bus-stops, construction sites, roadside billboards, in newspapers or magazines, and so forth; usually one ad spot out of every commercial break; trailers and previews; ‘next week on …’ snippets following television shows; appearances of stars on talk shows or entertainment news programs; interviews in industry or fan magazines; a toy promotion at a fast-food chain; a new ride at an amusement park; and so on. Even revenue generating synergy, such as a toy or clothes line, a CD or DVD, or a computer game, act as advertisements in their own right. Now, though, the product in question is a text in its own right. This allows advertisers to use the text as resource in constructing an image of that text, as with trailers that lace together multiple scenes from a film or program, for instance, or as with interviews that draw on a star’s public image.

Gray 2008: 37

This wide array of epitextual elements with a promotional aim are generally not translated by the audiovisual translator. Film posters, television promos, press releases, DVD covers, web sites and other various types of hype do not always coincide in the source and the target language versions. They are sometimes created from scratch in the target language and, when translated, they are frequently not commissioned to the same audiovisual translator who is translating or has translated the film or TV show.

This working scenario can affect the global quality of the final translation: translating the blurb on a film included on a DVD cover without having watched the film or translating a website related to a TV show without knowing the translation strategies chosen for this specific programme can result in inconsistent translations. Quality-concerned clients, fully aware of the implications of the translation process, as well as versatile translators, able to adapt to new formats and different media, are of the essence in this scenario.

Although the audiovisual translator’s exposure to the promotional aspects is generally kept to a minimum, this is not the case when it comes to trailers. Trailers are a specific type of epitextual component, whose translation is generally commissioned to audiovisual translators. According to Kernan (2004: 1), the trailer’s function is to act as an “aid in movie going decision making.” And she adds: “While trailers are a form of advertising, they are also a unique form of narrative film exhibition, wherein a promotional discourse and narrative pleasure are conjoined.” Trailers generally present a set of generic features: “some sort of introductory or concluding address to the audience about the film either through titles or narration, selected scenes from the film, montages of quick-cut action scenes, and identification of significant cast members or characters” (Kernan 2004: 9). The translator has to render these features in the dubbed version and overcome the most significant constraint: the lack of contextual information. Indeed, translators might not have information regarding the plot and characters, and if the transcript is made available it might not even contain the name of the characters, merely a transcription of their lines.

On the other hand, if “even the marketing of subsidiary products such as toys and models” are part of the paratextual world of a film or TV series, as stated by Stam (2000), the influence of these products in the actual translation must be highlighted. A clear example of this affects the translation of proper nouns in cartoons. Although meaningful, the name of the characters in some cartoons cannot be changed because promotional merchandising has already been created with an international name printed on it. For instance, Aladdin was kept as in the English version instead of using the Spanish version Aladino for the Spanish speaking target market.

All in all, this section has ascertained the presence of multiple paratextual features which can be conveyed in the dubbed version by the translator, transferred into the target language by another professional, or can be kept in the source language.

4. Paratextual elements in dubbing: the written translated script

If the written script can be considered a paratext of the audiovisual text, the written translation which is given to dubbing actors – once synchronised and linguistically revised –, which could be termed the dubbing script, could also be viewed as a paratext to the actual dubbed audiovisual text. However, it could also be considered a written text per se, that includes various paratextual components which facilitate the process of dubbing. These elements might contain: cover or introductory section with information concerning the title and the translator, footnotes, synchronisation and spotting symbols, and character lists.

It is common practice to include the original title, the title and the original translator’s name, either as part of the cover or as a separate section at the beginning. Footnotes are another type of paratext found in the written script for dubbing: these notes include indicators for other agents in the dubbing chain. For instance, a translator can make explicit the source of a terminological unit so that the linguist knows the term has been adequately documented, or a translator can explain a word play and propose additional translations for the dialogue writer to choose from.

At the synchronisation stage a set of symbols is added in order to help both voice talents and sound engineers to reach the three types of synchrony which create a credible product: (i) lip synchrony, i.e., the lip movement coincides both in the original and the dubbed version at critical points such as bilabial consonants so as to reach the illusion of a phonetic synchrony, especially in close-ups and shots where the lip movement is clearly visible; (ii) isochrony, that is, the target language version follows the pauses of the source text and is of the same length as the original version, and (iii) kinesic synchrony, in other words, the body and facial movements of the screen actors coincide with the content of the dubbed version. Chaume (2007: 210) lists the heterogeneous symbols used in dubbing in Spain, France, and Italy. For instance, (OFF) is used for a voice off in Spain and France, whereas its Italian counterpart is (FC). Another example would be (G) as an indication of a paralinguistic sound in Spain, which is rendered by (réac) in France or VERSO in Italy. These symbols are interspersed in the written script between brackets, as will be shown in an example below.

At the language revision phase, some additional indicators are added, as footnotes, as added text between brackets next to the dialogue or as a separate document. These indicators often include pronunciation guidance, generally referring to proper nouns.

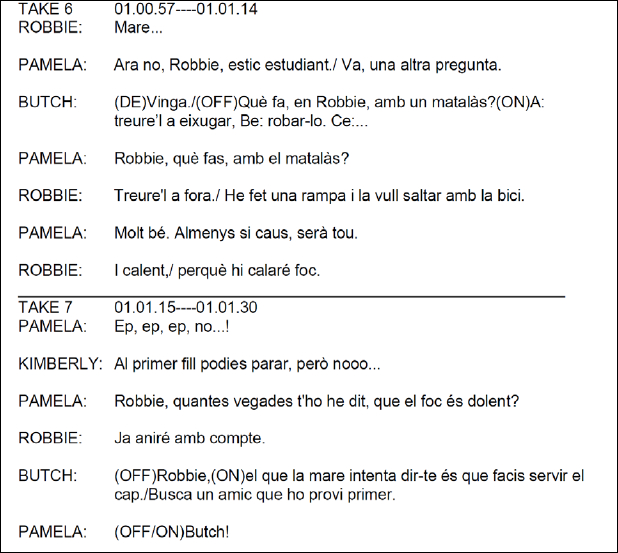

Finally, the written script for dubbing is segmented or spotted to facilitate the dubbing process. The dubbing unit is the take, a chunk of text of various lengths depending on the countries (Chaume 2007: 206): in Spain it varies from eight to ten lines with certain additional constraints. This segmentation is carried out either by the translator/dialogue writer, the dialogue writer or the director’s assistant depending on the dubbing studio, although software can occasionally be used to automatically segment the text. The initial and final time codes of each take are written and takes are physically separated by a line and numbered. All these paratextual features of the written script can be observed in Figure 1, from the series Normal, Ohio: the take number, the time codes for each take, a line separating the takes, the name of the character before the actual dialogue, and synchronisation symbols such as / (pause), ON (on screen), OFF (off screen), and DE (backwards). No translation is provided for this paragraph because the already mentioned paratextual features are the point of interest to be observed in this text, rather than the actual translation.

Figure 1

Written script for dubbing

All in all, the written text which is used to create the final audiovisual text in the target language can also be viewed as a text which includes paratextual elements, added by the various agents taking part in the dubbing process.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this article has transferred some key notions from the area of literary studies into the area of audiovisual translation, and has tried to describe paratextual elements found in audiovisual texts in the field of dubbing. In order to do so, two types of texts have been considered: on the one hand, the audiovisual text proper and, on the other hand, the written text which is used as a support to the dubbing process.

The present study has offered a broad overview based on the author’s experience in the field of dubbing; however, a thorough corpus analysis which encompasses other audiovisual translation transfer modes as well as practices from other professional contexts would undoubtedly offer a more detailed picture of this topic. The theoretical implications of such research are obvious: understanding the specificities of the audiovisual text and all of its components. Nevertheless, the results of such research could extend into the realm of practice, making translators aware of all the products related to the audiovisual text and of the way they are dealt with in the industry. Although dubbing seems to have fallen into partial oblivion in the academic arena, due to the supremacy of subtitling and the powerful emergence of new accessibility-related transfer modes, there are still many research issues to be tackled in the field of dubbing, both from a theoretical and an applied point of view.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Fergal Denn, Pilar Orero and Pablo Romero-Fresco for their useful comments on an earlier version of this paper. This article is part of the Spanish project FFI2009-0827 and of the Catalan research group Transmedia Catalonia, funded by Generalitat de Catalunya (2009SGR700).

Bibliography

- Böhnke, Alexander (2007): Paratexte des Filmes. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

- Bruno, Giuliana (1993): Streetwalking on a Ruined Map. Cultural Theory and the City Maps of Elvira Notari. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Cary, Edmond (1960): La traduction totale. Babel. 6(3):110-115.

- Chaume, Frederic (2003): Doblatge i subtitulació per a la TV. Vic: Eumo.

- Chaume, Frederic (2004): Cine y traducción. Madrid: Cátedra.

- Chaume, Frederic (2007): Dubbing practices in Europe: localisation beats globalisation. Linguistica Antverpiensia New Series. 6:203-219.

- Delabastita, Dirk (1989): Translation and mass-communication: film and T.V. translation as evidence of cultural dynamics. Babel. 35(4):193-218.

- Díaz-Cintas, Jorge (2003): Teoría y práctica de la subtitulación. Barcelona: Ariel.

- Díaz Teijo, José Tomás (1997): La traducción de los títulos de películas del inglés al castellano: procedimientos y resultados. In: José Miguel Santamaría, Eterio Pajares, Vickie Olsen, et al. eds. Trasvases culturales: literatura, cine, traducción. Vitoria: UPV, 131-141.

- Fuentes Luque, Adrián (1998): La traducción de títulos de películas y series de televisión: ¿Y esto… de qué va? Sendebar. 8-9:107-114.

- Genette, Gérard (1997): Paratexts. Thresholds of interpretation. (Translated by Jane E. Lewin) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- González Ruiz, Víctor María (2000): La traducción del título cinematográfico como objeto de autocensura. In: Allison Beeby, Doris Ensinger and Marisa Presas, eds. Investigating Translation. Selected Papers from the 4th International Congress on Translation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 161-169.

- Gottlieb, Henrik (2000): Texts, Translation and Subtitling. In Theory and in Denmark. In: Henrik Gottlieb, ed. Screen Translation: Six Studies in Subtitling, Dubbing and Voice-over. Copenhaguen: Center for Translation Studies, University of Copenhaguen, 1-40.

- Gray, Jonathan (2010): Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Paratexts. New York: New York University Press.

- Gray, Jonathan (2008): Television pre-views and the meaning of hype. International Journal of Cultural Studies. 11(1):33-49.

- Kernan, Lisa (2004): Coming Attractions: Reading American Movie Trailers. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Kolstrup, Søren (1996): The film title and its historical ancestor. P.O.V. 11(1):33-49. Visited on 27 April 2010, http://pov.imv.au.dk/Issue_02/section_1/artc1B.html.

- Kreimeier, Klaus and Stanitzek, Georg, eds. (2004): Paratexte in Literatur, Film, Fernsehen. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

- Lambert, José and Delabastita, Dirk (1996): La traduction de textes audiovisuels: modes et enjeux culturels. In: Yves Gambier, ed. Les transferts linguistiques dans les média audiovisuels. Lille: Presses Universitaires de Lille, 33-60.

- Martí, Roser and Zapater, Maria (1993): Translation of titles of films. A critical approach. Sintagma. 5:81-87.

- Matamala, Anna (2010): Translations for dubbing as dynamic texts. Strategies in film synchronisation. Babel. 56(2):101-118.

- Matamala, Anna (2009): Main challenges in the translation of documentaries. In: Jorge Díaz-Cintas, ed. In So Many Words: Translating for the Screen. London: Multilingual Matters, 109-120.

- Metz, Christian (1994): Pour servir de préface. In: Nicole De Mourgues. Le générique du film. Paris: Méridiens Klincksieck, 6-9.

- Mourgues, Nicole de (1994): Le générique du film. Paris: Méridiens Klincksieck.

- Nedergaard-Larsen, Birgit (1993): Culture-bound problems in subtitling. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology. 1(2):207-241.

- Peng, Ying (2007): Translation of Film Titles with the application of Peter Newmark’s translation theory. Sino-US English Teaching. 4(4). Visited on 1 September 2010, http://www.linguist.org.cn/doc/su200704/su20070415.pdf.

- Serrano Fernández, Luis (2001): La traducción de los títulos de películas inglés-español en un contexto determinado y determinante: España 1977-1980. Sendebar. 12:153-178.

- Stam, Robert (2000): Film theory. An introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Stanitzek, Georg (2005): Texts and paratexts in media. Critical Inquiry. 32(1):27-42.

- Stanitzek, Georg (2009): Reading the title sequence (Vorspann, générique). Cinema Journal. 48(4):44-58.

- Straw, Will (2010): Letters of introductions: Film credits and cityscapes. Design and Culture. 2(2):155-166.

- Yin, Lu (2009): On the translation of English movie titles. Asian Social Science. 5(3). Visited on 1 September 2010, http://www.bcl.edu.ar/spip/IMG/pdf/luyin-2.pdf.

- Zabalbeascoa, Patrick (1997): Dubbing and the nonverbal dimension of translation. In: Fernando Poyatos, ed. Nonverbal Communication and Translation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 327-342.

- Zabalbeascoa, Patrick (2001): El texto audiovisual: factores semióticos y traducción. In: John Sanderson, ed. ¡Doble o nada! Actas de las I y II Jornadas de doblaje y subtitulación. Murcia: Universitat d’Alacant, 113-126.

- Zabalbeascoa, Patrick (2005a): Prototipismo textual, audiovisual y traductológico: una propuesta integradora. In: Raquel Merino, José Miguel Santamaría and Eterio Pajares, eds. Trasvases culturales: literatura, cine, traducción 4. Vitoria: UPV, 177-194.

- Zabalbeascoa, Patrick (2005b): Humor and translation – an interdiscipline. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research. 18(2):185-207.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Written script for dubbing