Résumés

Abstract

Hybrid organizations are those striving to balance business operations with social and environmental goals. The previous literature has largely disregarded the strategies that these organizations use to avoid mission drift, or the risk of losing sight of their social missions in their efforts to generate revenue. In this paper, we draw on the case of a communitarian bank in Brazil to investigate what strategies hybrid organizations mobilize to avoid mission drift in extreme institutional contexts. We argue that by developing the ability of “embedding within the local community”, hybrid organizations are better equipped to guarantee the sustainability of their hybrid nature.

Keywords:

- nonprofit sector,

- microfinance,

- extreme institutional context,

- mission drift,

- emerging country

Résumé

Les organisations hybrides sont celles qui s’efforcent d’équilibrer leurs opérations commerciales avec des objectifs sociaux et environnementaux. La littérature précédente a largement ignoré les stratégies que ces organisations utilisent pour éviter la dérive de mission ou le risque de perdre de vue leurs missions sociales dans leurs efforts pour générer des revenus. Dans cet article, nous nous inspirons du cas d’une banque communautaire au Brésil pour examiner les stratégies que les organisations hybrides mobilisent pour éviter la dérive des missions dans des contextes institutionnels extrêmes. Nous soutenons qu’en développant la « capacité d’intégration dans la communauté locale », les organisations hybrides sont mieux équipées pour garantir la durabilité de leur nature hybride.

Mots-clés :

- secteur sans but lucratif,

- microfinance,

- contexte institutionnel extrême,

- dérive des missions,

- pays émergent

Resumen

Las organizaciones híbridas son aquellas que se esfuerzan por equilibrar las operaciones comerciales con los objetivos sociales y ambientales. La literatura anterior ha ignorado en gran medida las estrategias que utilizan estas organizaciones para evitar la deriva de la misión o el riesgo de perder de vista sus misiones sociales en sus esfuerzos por generar ingresos. En este documento, nos basamos en el caso de un banco comunitario en Brasil para investigar qué estrategias movilizan las organizaciones híbridas para evitar la deriva de la misión en contextos institucionales extremos. Argumentamos que al desarrollar la capacidad de “integrarse dentro de la comunidad local”, las organizaciones híbridas están mejor equipadas para garantizar la sostenibilidad de su naturaleza híbrida.

Palabras clave:

- sector sin fines de lucro,

- microfinanzas,

- contexto institucional extremo,

- deriva de la misión,

- país emergente

Corps de l’article

Hybrid organizations combine different organizational forms and practices that allow the coexistence of different values, thus crafting a balance between commercial and social objectives (Dogherty, Haugh and Lyon, 2014). With their pursuit of positive social change through the use of market mechanisms, hybrid organizations have increased in importance in the context of rising sustainability challenges (Battilana, Lee, Walker and Dorsey, 2012). Examples of hybrid organizations abound around the world. For instance, social enterprises are organizations that focus on providing goods or services (or both) to solve the social problems that are not effectively addressed by existing organizations (Mair & Marti, 2006; Ramus and Vaccaro, 2017; Smith, Gonin, & Besharov, 2013), as in the case of work integration social enterprises that help long-term unemployed citizens to transition back into the labor market (Battilana, Sengul, Pache, and Model, 2015). Cooperatives, with their dual mission of attending to the social needs of members while being financially sustainable, also fall within the category of hybrids (Ashforth and Reingen, 2014; Bouchard & Michaud, 2015). Another prominent example is found in the microfinance industry, where organizations that provide credit to clients who are not eligible for traditional loans must combine a banking and a development logic (Battilana and Dorado, 2010).

However, pressures for better financial performance have prompted many hybrids to drift away from their original missions (Mia and Lee, 2017; Ebrahim, Battilana and Mair, 2014) or practices (Maîtrot, 2018). The risk of losing sight of their social missions in their efforts to generate revenue has been termed “mission drift” (Ebrahim, Battilana and Mair, 2014; Almandoz 2012). This phenomenon is particularly present in the global context of microfinance, an industry which delivers small loans and other financially related services to more than 150 million people (Armendáriz & Morduch, 2010). Historically, microfinance institutions (MFIs) have been hybrid in nature, applying financial efficiency to aid social development (Yunus, 2007; Ebrahim, Battilana & Mair, 2014; Marconatto, Barin-Cruz & Avila Pedrozo, 2016). However, the general financialization of the world economy and organizations (Zwan, 2014) in recent years has led many MFIs to prioritize their financial orientation above their social purpose. Many of the financial markets, scholars, international agencies (e.g., CGAP, World Bank, USAID) and the MFIs themselves (e.g., the Indonesian BRI) have been advocating for the adoption of profit-seeking business models as the best way to strengthen the microfinance industry (Getu, 2007; Yunus, 2011; Kent & Dacin, 2013; Ebrahim et al., 2014; Marconatto et al., 2016a).The imperative for profit maximization has pushed microfinance institutions (MFIs), which were originally conceived for outreach to the poorest of the poor, to instead seek more profitable clients (Mia and Lee, 2017; Battilana and Dorado, 2010; Hudon and Sandberg, 2013; Kent and Dacin, 2013; Khavul, 2010). In other words, mission drift in microfinance translates into the abandonment of the hybrid nature of microfinance by prioritizing the financial purpose of an operation (Epstein & Yuthas, 2010; Copestake, 2007a, 2007b; Getu, 2007; Cornforth, 2014). The most serious consequences of mission drift for hybrid MFIs are as follows: the move towards a preference for less-poor target recipients (Schreiner, 2002; Mersland & Strøm, 2010; Yunus, 2011) and the poor borrowers’ loss of their usual sources of capital and resources (e.g., donors and governmental agencies) (Epstein & Yuthas, 2010). Consequently, mission drift results in the exclusion from the microfinance field of the very clientele that motivated its creation, something that harms the social purpose of MFIs and ultimately creates a trap for the poor (Yunus, 2011).

Previous studies have recognized the pervasiveness of this phenomenon by identifying the main sources of mission drift (Mia and Lee, 2017; Copestake, 2007a; Getu, 2007; Arena, 2009; Mersland & Strøm, 2010; Hartarska & Mersland, 2012) and showing how organizations may fall into this trap. However, we identify two blind spots in this literature. First, the previous studies on mission drift have paid very little attention to organizations that were able to maintain their hybrid nature despite being exposed to institutional pressures. This organizational capability seems of particular importance in the microfinance industry considering the increasing claim that many MFIs have been abandoning their initial missions and undertaking commercial practices similar of traditional financial organizations (Yunus, 2011). Second, although the institutional context has been identified as an influential source of pressure for mission drift (Churchill, 1999; Hung, 2006; Bhatt & Tang, 1998; Bruton, Khavul & Chavez, 2011; Boehe & Barin-Cruz, 2013), very few studies (Barin Cruz et al., 2016) have focused on and theorized about the empirical cases of organizations that have undertaken concrete actions to avoid mission drift, operating in contexts that are or are becoming extreme. In particular, in the case of MFIs, these organizations usually target poor populations living in areas of increased social and environmental risks, greater uncertainty and scarcer resources. Knowledge on regarding the managerial practices of organizations in extreme operating contexts is still rare, despite the number of organizations that operate under these circumstances. Thus, our study aims to address these blind spots and focuses on the following research question: What strategies do hybrid organizations employ to avoid mission drift in extreme contexts?

In this paper, we address this question by investigating the case of one hybrid organization operating in an extreme institutional context that has been successfully resisting mission drift for more than two decades. Banco Palmas is an MFI located in the northeastern region of Brazil, one of the poorest regions in the Americas. We analyzed a dataset comprising internal and external documents, interviews, notes and the shadowing of key employees in the MFI to demonstrate how the extreme institutional context led to the development of a key mechanism to avoid mission drift, i.e., embedding within the local community. This mechanism permeates all other strategies implemented by the organization to avoid mission drift.

Our study offers a two-fold contribution to the understanding of the sustainability of hybrid organizations (Pache & Santos, 2010; Ebrahim, Battilana and Mair, 2014). First, we expand the general knowledge on how hybrid organizations avoid mission drift. We complement the previous analyses of the pressures experienced by a particular type of hybrid, an MFI, to drift away from its social mission (Woller, Dunford & Woodworth, 1999), and we unveil a series of strategies mobilized by such organizations. Second, we argue that in extreme operating environments, which are the most likely contexts for several MFIs, embedding within the local community becomes a central mechanism to maintain an organization’s hybrid nature. By proposing both contributions, we go beyond the previous studies in the field that have been limited to the documentation of how hybrid organizations fall into the trap of mission drift, and we present concrete strategies that have allowed MFIs to become sustainable over time.

Literature Review

Mission Drift as a Threat to Hybrid Organizations

The previous research has indicated that combining logics (e.g., social and commercial) might expose hybrid organizations to conflicting demands from their environment (Pache & Santos, 2010), generating trade-offs between their social activities and their commercial activities (Ebrahim, Battilana and Mair, 2014; Hudon and Sandberg, 2013). In the case of MFIs, mission drift occurs when an organization moves away from poorer customers in search of more profitable customers (Woller et al., 1999). There is ample evidence that more profit-oriented lenders tend to drift towards better-off clients, lending to more urbanized populations and to fewer women (Morduch, 2000; Cull, Demirgüç-Kunt & Morduch, 2007, 2009a, 2009b; Mersland & Strøm, 2010). Financial MFIs are less likely to provide the types of nonfinancial and support services that are important to the poorest communities and are more likely to increase interest rates and demand collateral (Churchill, 1999; Schreiner, 2002; Mersland & Strøm, 2010; Sinclair, 2012). Moreover, as Yunus (2011) notes, financially oriented microfinance practices can disrupt the relationships already established between MFIs and their communities. There have been unfortunate reports about how some financial MFIs have caused the over-indebtedness of clients, inflicted violence and even caused the deaths of borrowers (e.g., see Business Insider, 2012; Sinclair, 2012, Bastiaensen, Marchetti, Mendoza & Pérez, 2013; Dattasharma, Kamath & Ramanathan, 2015).

Previous studies have identified several sources of mission drift. The regulatory environment is one of these sources (Ebrahim, et al. 2014). Currently, in most countries of the world, there are still no legal provisions that accommodate hybrid organizations; in fact, entrepreneurs usually end up choosing either for-profit or not-for-profit forms (Austin, Stevenson & Wei-Skillern, 2006; Renko, 2013), even if these legal forms do not completely fit their needs. It is usually difficult for MFIs to formalize (Bhatt & Tang, 1998) and conform to a regulated status without abandoning their social purpose for the sake of financial viability, i.e., formalization through the adoption of a bank-like legal structure carries with it the risk of prioritizing profitability simply to cover the expenses imposed by regulation.

A second source is related to the governance of the organization, i.e., the mechanisms within an organization that broadly determine how organizational resources are used (Mair et al. 2015), and the sources of funding (Mia & Lee, 2017). A financially minded board can have a negative impact on the social performance of MFIs (Hartarska & Mersland, 2012; Jones, 2007). Similarly, funders and partners with a strong market orientation may produce a negative outcome (Getu, 2007; Mia and Lee 2017). Studies have shown that financial MFIs receive more resources than those focused on the social impact of their activities (Hartarska & Nadolnyak, 2008; Beisland & Mersland, 2012). However, evidence has pointed to the fact that in choosing to utilize commercial sources of funding, MFIs are directed to focus more on commercial gain or profit motives, causing them to deviate from their mission of serving the poorest of the poor (Mia and Lee 2017).

A third source is related to internal aspects of the operation, in particular, the leadership and the workforce. Previous studies in the context of MFIs have shown that organizations with leaders who subscribe to a free market ideology are more prone to mission drift (Jones, 2007, Getu, 2007). Mission drift may be further promoted by the organization’s human resources practices, such as financially biased systems of recruitment, training and socialization of employees (Battilana & Dorado, 2010; Cornforth, 2014), credit agents operating under inappropriate incentive structures (Aubert et al., 2009), or from the ’displacement of decision-making processes to the branches’, in a less top-down approach (Maîtrot, 2018: 1). For instance, in Battilana and Dorado (2010), the Bolivian MFI BancoSol undermined its hybrid mission by adopting an ’integration strategy’ for recruiting and socializing its personnel. This organization hired employees with previous professional backgrounds in either finance or social work. However, during the process of socializing the two groups into a common hybrid orientation, major conflicts arose, eventually undermining the integrity of the MFI’s mission.

Finally, the competitive context of hybrid organizations has been mentioned as an important driver of mission drift (Battilana et al. 2012). The fierce competition for clients, funds and grants (Getu, 2007; Jones, 2007; Aubert et al., 2009) and high operational costs (Arena, 2009; Serrano-Cinca & Gutierrez-Nieto, 2014) have been found to be incentives for MFIs to abandon their hybrid orientation.

Interestingly, although these sources of pressure have been documented and analyzed, there is conflicting evidence regarding how hybrid organizations manage these tensions internally. On the one hand, scholars find support for the use of the social mission as a force for the strategic direction (Lumpkin et al. 2013), therefore favoring one part of the equation. On the other hand, genuine or “integrated” hybrids, i.e., organizations where everything produced has both social value and commercial revenue, are said to be in a better position to make selective use of and innovate in the context of multiple logics (Mair, Mayer and Lutz, 2015; Battilana et al. 2012). Nevertheless, little is still known about how hybrid organizations in extreme contexts address these tensions.

Influence of Extreme Institutional Contexts on Mission Drift

The pressures towards mission drift can originate from different sources; however, the institutional context in which they operate will affect the way in which organizations perceive them as risks (Button, et al. 2011). Institutions are production systems, enabling structures or performance scripts that reduce the complexity and uncertainty of the environment (Jepperson, 1991; Meyer & Rowan, 1983; Zucker, 1977). In extreme institutional contexts, the actors must cope with greater risk and uncertainty, while also having to manage scarcer resources (Barin-Cruz et al. 2015). Countries in which the institutions are unstable and fragile and whose governments have limited capacity to provide basic support are examples of extreme contexts that greatly affect the strategies that are available to organizations to pursue their activities (Barin-Cruz et al. 2015). Examining the sources of mission drift mentioned in the previous subsection in more depth, we can appreciate how the characteristics of the environment may make it more difficult for hybrid organizations to avoid mission drift.

First, a country’s regulations determine an important part of the transaction costs borne by organizations, including MFIs (Choi, Kim & Kim, 2009; Getu, 2007; Arena, 2009; Ebrahim et al., 2014; Churchill, 1999). In countries where there is a properly tailored regulation system for hybrid organizations, MFIs have a better chance of minimizing costs and safeguarding their mission (Ebrahim et al., 2014). In contrast, with a stifling and inefficient bureaucracy, which is often present in extreme contexts, MFIs face higher costs and more obstacles to formal operation, a reality that could force an MFI towards a more financial mindset.

Second, the sources of funding and governance practices are highly affected by the institutional context they inhabit (Getu, 2007; Epstein & Yuthas, 2010; Sinclair, 2012). Despite the historical focus of MFIs on social development, financially oriented principles began to pervade the microfinance field in the 1990s. This trend was seen in the increase in the number of financially minded scholars and practitioners populating the major international agencies related to microfinance (Woller et al., 1999) – organizations such as USAID, CGAP and World Bank. Governments followed suit, borrowing these ideas to further promote the financialization of microfinance (Sinclair, 2012). Under the label of a ’microfinance revolution’, the financial market, agencies and governments have instituted support for the financialization of MFIs through different methods; financial MFIs received more resources than those focused on the social impact of their activities (Hartarska & Nadolnyak, 2008; Beisland & Mersland, 2012); financially minded consultants became available for MFIs interested in migrating towards profit-seeking models (Sinclair, 2012); and scholars endorsed the transformation of the sector towards financialization (e.g., Ledgerwood & White, 2006). We expect that in extreme contexts, where the scarcity of resources is prominent, an “easy way out” for organizations would be to resort to financialization. Both the deeper scarcity and the higher uncertainty in accessing a constant stream of capital can provide strong pressures towards mission drift (Jones, 2007; Serrano-Cinca & Gutiérrez-Nieto, 2014; Cornforth, 2014).

Finally, in terms of internal operations and competitive strategies, many MFIs have been caught up in the ongoing wave of financialization that is changing the structures of modern organizations and marketplaces (Zwan, 2014). This phenomenon is clearly seen in the adherence of many MFIs to financial language, norms, values and performance measures, short-term business outlooks and downsizing strategies (Kent & Dacin, 2013). However, the forces of pressure for mission drift differ according to the surrounding reality. This phenomenon is evident in the differences in the ’discourse of microfinance’ between the south, with more extreme contexts, and the north, with more reliable and stable institutional contexts. While countries of the south have been more prone to buying into the imperatives of scale, sustainability and profitability, the north is attached to the ideal of the ’community bank’ (Johnson, 1998). In our research, we specifically targeted an organization that is based in the south and is in a particularly extreme context. In the following section, we show how this organization managed the pressures of mission drift and was able to maintain its hybrid nature.

Table 1

Latin American MFIs

Methodology

Research Context

Microfinance institutions in Latin American have consistently adopted a commercial orientation, providing services to enterprises with insufficient access to financial services, and to the unbanked in general (Berger, 2006; Mix Market, 2003). Latin American MFIs “have more assets, leverage more equity and attract more commercial investment than MFIs in other regions. They also reach fewer clients and achieve marginal returns” (Mix Market, 2003, p.1). These MFIs tend to operate more as private businesses focusing on the demand for entrepreneurial credit in the informal sector, more markedly in urban areas (Berger, 2006). Unlike African or Asian microfinance models, the dominant approach is individual lending, even though there are few experiences of group banking[1] in countries like Brazil and Colombia and village banking in Mexico and Peru (Ella, 2013). Recently we witnessed a great number of NGOs converting to for profit institutions to be in a better position to reach more sources of funding and to compete with a growing number of large banks that have reached “down market” into microfinance (Berger et al., 2006). Criticism followed due to the risk of “mission drift” of the institutions providing microcredit in the region, and some NGOs decided to maintain the nonprofit status to continue to target the most poor (Berger et al., 2006). summarizes key information about the Latin American MFIs.

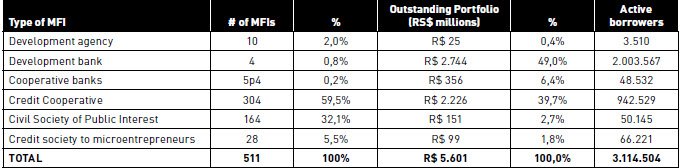

Brazil followed a somewhat different path than its Latin American counterparts. Since the 1990s, we witnessed the rise of microfinance in Brazil coming mostly from a number of municipal and state initiatives directed at fostering production-oriented microcredit at lower interest rates to low-income individuals and micro-entrepreneurs (Franca Filho et al. 2012). Emerging from a long history of different solidarity finance initiatives are community development banks (CDB), which are microfinance institutions dedicated to income and work generation in areas of social vulnerability (Franca Filho et al. 2012) by valuing the potential of the mobilization of local investments based on networks of social relations between individuals as a form of collateral and control that is not asset-based (Abramovay and Junqueira, 2005). Some characteristics that differentiate these institutions from other MFIs are highlighted by Franca Filho et al. (2012): proximity relations take precedence as an important requisite in the process of granting credit; bank is created based on a genuine community desire; collateral and control are based on close relationships and mutual trust; use of local social currencies functioning as consumption incentive tools. Following these characteristics, CDBs located in urban areas often operate under individualized credit methods, in opposition to those in rural areas that may also adopt collective approaches (such as the use of lending groups) (Marconatto et al. 2017). In Table 2, we present a snapshot of Brazilian MFIs.

In this paper, we study the pioneer CDB in Brazil. Banco Palmas, founded in 1998 in an extreme context on the outskirts of Fortaleza-Brazil, a place called Conjunto Palmeiras neighborhood, where poverty-related problems abound in the fifth most unequal city in the world (UN-Habitat, 2013). This MFI emerged in the context of the social and economic struggles of a destitute community of approximately 30 thousand people (Segundo & Magalhães, 2003, 2008; Banco Palmas, 2012). The community bank began as a grassroots initiative mandated with the economic emancipation of the local inhabitants, who were trapped in deep poverty.

Currently, the Banco Palmas is financially self-sustainable, has approximately 25 employees, and disburses approximately 1.5 million US dollars each year in loans that are spread over 5,000 annual credit operations. Approximately 75% of the loans are very small and target local people who live in desperate poverty. Most of this credit is conferred to the beneficiaries of social programs, such as Bolsa Família, and has low interest rates. However, the bank also reaches local small businesses that need money to grow and even those that require assistance with cash flow. The innovations promoted by Banco Palmas include the implementation of solidarity stores, the support of the production of basic consumer goods inside the community, professional training for youth, and the promotion of a fashion week led by local needlewomen, all of which have made the case of Banco Palmas famous nationally and abroad. Among the awards and mentions received by Banco Palmas was the 2013 AICESIS[2] Award. Moreover, to spread community banks across Brazil, Banco Palmas created and currently leads a network of over one hundred MFIs dispersed throughout the country. The bank provides training and consulting services to other communities interested in having their own bank. Such efforts have been propelled by key partnerships developed with public programs and agents, such as Bolsa Família and the Secretary of Solidarity Economy (SENAES), respectively. The latter has played a major role in the expansion of community organizations, such as Banco Palmas (Pozzebon et al., 2014). In a recent census, more than 19 thousand social enterprises were mapped in Brazil (IPEA, 2016). However, the same source shows that only 1,7% of these initiatives are related to the provision of financial services to the poor. This number indicates that there still is much terrain to be gained regarding financial inclusion.

Table 2

Status of Brazilian MFIs in September 2015

Research Design

The research approach for this study is a revelatory case design (Stake, 1998). The case of Banco Palmas (see table 3 for more data) is meaningful for the investigation of our research question for two reasons. First, the organization provides relevant examples of how a hybrid MFI can be successful in avoiding different pressures towards mission drift. We adopted commonly used measures of mission drift – a target public, the scope of the portfolio of financial and nonfinancial services, and the average loan size (Schreiner, 2002; Mersland & Strøm, 2010) – and accounting for inflation, and we find that the MFI has not drifted away from its founding orientation. Additionally, despite the dire financial circumstances of its clients, Banco Palmas has achieved and continues to maintain high repayment rate levels.

Second, the northeast of Brazil and, particularly, the Conjunto Palmeiras region, can be categorized as an extreme context. For context, we mean a particular action area (such as a region) where institutional actors – individual and collective – have roles, capacities, interests and relationships that are influenced and/or governed by rules and incentives (Williamson, 2000). An extreme context would be characterized by legal, political and financial institutions with low stability and efficiency (Barin Cruz et al., 2015). In the particular region where Banco Palmas operates, access to capital is difficult to obtain and the levels of business formality and market efficiency are lower.

Table 3

Key Characteristics of Banco Palmas

* estimated dollar exchange rate of approximately US$ 1 to R$ 4 (Brazillian Currency = Reals)

(a). According to IPECE (2014), 17,1% of all Conjunto Palmeiras’ dwellers live on less than US$25,00 per month, a level classified as extreme poverty; (b) Instituto Palmas (2011).

Data Collection

One of the authors conducted formal interviews in Portuguese with all seven key employees of Banco Palmas (table 4) in 2012. We also maintained contact with the organization over the following years to better understand how their strategies and business model evolved. The interviews consist of eleven hours of recorded audio, which were later transcribed verbatim and then translated to English. The interviews occurred at Banco Palmas and followed a semistructured protocol. The main focus was to identify and understand the dominant sources of pressure towards mission drift faced by the MFI, as well as the strategic actions taken to avert such threats. The diverse responsibilities of the staff interviewed led to the strategic and operational view of Banco Palmas and its reality regarding the phenomenon of mission drift.

Table 4

Interviewed Actors

This information was triangulated with other sources, i.e., documents and shadowing by one of the authors. We had access to a total of 185 documents from Banco Palmas, which included board meeting minutes, internal communications, a book about the organization, operational controls, manuals, performance reports and pamphlets. Many of these documents were confidential. Taken together, the documentation amounted to nearly two thousand pages. These pieces of information helped us to understand the history and projects developed by the organization.

Additionally, one of the authors had the opportunity to conduct a participant observation of the organization’s operations. After months of negotiation, Banco Palmas allowed this author to engage in shadowing, a technique through which the researcher closely follows individuals, thus witnessing the phenomena and organizational situations that occur during a given time interval (McDonald, 2005). Shadowing is particularly suitable to this type of research because the direct access to the world of the research subjects aids in obtaining a better understanding of emergent concepts and understudied phenomena (McDonald, 2005). Ten employees were followed separately during the execution of their daily tasks (see table 5), which amounted to 70 hours of shadowing and 23 single-spaced pages of descriptive field notes. Activities such as risk screening, lending and controlling were covered step-by-step. The participant observation provided us with rich information about how the organization performed its daily routines and how the organization tried to maintain its distinctiveness when performing mundane practices.

Data Analysis

The data analysis for this study was performed in two stages. We first analyzed the organization’s internal and external documentation in search of evidence that provided initial insights into the forces pressuring it towards financialization. Combined with a literature review, this stage allowed us to identify the main sources of mission drift at Banco Palmas, which helped in structuring our results section. The second stage involved an inductive coding process (Miles & Huberman, 1994), with categories emerging from the data (Corbin & Strauss, 1998). Atlas.ti, a software for the qualitative analysis of textual and graphical data, was used in both stages. We used the interviews and our field notes collected during the shadowing process to identify the strategic actions developed by the organization to respond to the threats identified in the first stage of the analysis. Through this process, a key element emerged to explain how the organization was able to avoid mission drift and thereby maintain its hybrid orientation, i.e., the mechanism of “embedding within the community”.

Table 5

Observation data

Findings

Strategies to avoid mission drift in extreme institutional contexts

In this section, we identify the main responses to the sources of mission drift faced by Banco Palmas. Based on the literature, we considered the following four different main challenges: regulatory (Austin et al. 2006; Renko, 2013); sources of funding (Mia & Lee, 2017); composition of the board and workforce (Battilana & Dorado, 2010; Pache &Santos, 2013; Canales, 2013; Ebrahim et al. 2014); and competition (Battilana et al. 2012). Table 6 summarizes the relationship between the four ’sources of mission drift’ identified and the eight ’strategic actions’ undertaken by the organization, each of which will be described in detail in the following text.

Table 6

Sources of Mission Drift and Strategies from Banco Palmas (continuation)

Source 1: Regulatory challenges

Strategy 1: Operating as a not-for-profit organization

Banco Palmas has opted for the “Civil Society Organization in the Public Interest” (OSCIP) format instead of the for-profit format. Since Banco Palmas was created in 1999, many other socially oriented MFIs have adopted this same legal structure as a way to reduce the mission drift risk (Alves & Soares, 2006). However, even though OSCIPs are formal institutions, they do not have the financial capabilities and privileges of traditional financial institutions, such as banks.The reason given by the manager of the organization for this decision is as follows: to operate with a dual objective, the required operational flexibility is high, and therefore, it would not be viable to adopt the traditional bank status and accomplish its aims.

It is clear that the MFI’s clientele generally fail to fulfil most of the requirements imposed by traditional banks. Although Banco Palmas has a structured loan workflow, both the bureaucracy involved and its rigidity are minimized. In some situations, only one piece of personal identification is required to receive a loan. Increased complete formality in this particular institutional context would preclude such flexibility, with a resulting decline in the operational capacity to fight poverty and a relinquishing of Banco Palmas’ social mission.

We can lend money without any kind of formal profile checking, collateral or income proof. We can also issue social currency in our neighborhood… Everything because we have other values and principles that do not work well within the existing formal regulation in Brazil

Segundo and Magalhães, 2008, p. T-16 – U-16

The regulations of traditional financial institutions demand adherence to a set of rules that are impossible for either Banco Palmas or its clients to follow. Examples include the mandatory deposits and governance apparatuses imposed on banks and the requirements of legally bound collateral and guarantors for clients. Thus, resisting a bank-like formalization represents a general strategy to avoid mission drift because the MFIs risk losing the capacity to deliver on their promise of social development if they are compelled to abide by the regulations that are necessary for banking formalization.

Strategy 2: Supporting the institutionalization of community banks

Banco Palmas promotes the proliferation of hybrid organizations motivated by the belief that the more common this type of organization becomes, the greater the capacity to guarantee their endurance and exert political leverage will be. Some organizations support Banco Palmas in this effort (Pozzebon et al., 2014), i.e., both national (e.g., National Bank for Economic and Social Development – BNDES – and Secretary of Solidarity Economy – SENAES) and international (Columbia University and Halloran Philanthropies) organizations. Banco Palmas’ staff provides technical assistance that is tailored to each new community bank requiring its services. The service begins with the mobilization of local communities and includes financial and operational training for the management of the new community bank.

Banco Palmas is a solidarity economy initiative. We can state this because … (e) it stimulates the creation of collaborative networks connecting producers and consumers

Banco Palmas, 2010, p. 28-29

Banco Palmas lobbied for the creation of a new formal legal entity that would accommodate a hybrid identity. Banco Palmas mobilized political partnerships with congressional representatives to draft Bill 93/2007, which focuses on broadening the financial capability of “people banks of solidary development”, including community banks. On the frequent occasions that the leader of Banco Palmas meets with high ranking politicians, he mentions this bill, which still awaits approval, and its essential importance for community banks and for the alleviation of poverty.

We do lobby to convince them that the community banks are a viable and positive alternative for Brazil and that it needs more resources in order to multiply itself. Our greatest effort is to integrate the community banks into the Brasil Sem Miséria, the biggest social project going on in Brazil. The community banks are not part of it because they are not regulated

Interview P2

Collecting and lending the savings of their own clients is one of the competences envisaged by the bill. Such capacity could facilitate the survival and the independency of banks similar to Banco Palmas, as it could also fuel and accelerate their growth.

Community banks should be able to collect savings and lend them back according to the criteria defined by the community… That is why we need to approve a legal format tailored for community banks. Achieving it means taking a definitive step towards a National System of Solidarity Financing

Segundo and Magalhães, 2006, p. 51

Source 2: Sources of funding and governance

Strategy 3: Safeguarding the ownership and control of the organization

To maintain independence and a hybrid mission, Banco Palmas procures loan funds from development-oriented investors and organizations, mainly public banks. The importance of the diligent repayment of these social investors is twofold. The MFI maintains steady access (predictability) to this fundamental resource, and it does not need to look for financially oriented funders who, by their nature, have the power to set contracts that favor the profit-seeking behavior that may compromise the hybrid orientation of microfinancing.

Our credit operation is sustainable because we can count on a public bank that lends a fund of over R$1.5 million, which we use as a loan fund. Our prices [the interest rates of Banco Palmas’ loans] allow us to repay them just all right

Interview P1

To guarantee that its social investors will be reimbursed, Banco Palmas works with substantial financial spreads, contracting capital at 8% and lending at 40%, on average. Additionally, the bank has developed other sources of income – four social businesses and a community store – to achieve a higher level of independence from financially driven lenders.

In addition to ensuring financial returns to investors in loan funds, Banco Palmas requires additional nonrecoverable capital for other operational expenses. Although the credit funds are financially sustainable, many of the nonfinancial services it offers are not. The continued provision of these services relies on external monetary injections. These provisions might produce deficits that can lead to a takeover of the organization by financial agents (Jones, 2007). To avoid this outcome and keep the reins of the MFI in its own hands, Banco Palmas seeks development-oriented sources of capital that are unconditional. The community bank receives the bulk of its financial resources from governmental organizations and private funders that are dedicated to social development. The community bank may also accept money from financially oriented agents if necessary, but only if it is free of any mechanism of control.

All the money we receive does not imply external control. We’ve always put that very clearly. We get donations and grants from government, public and private companies, private funds dedicated to social development. However, this doesn’t mean that they can decide our destiny

Interview P2

Strategy 4: Composing a board with the members of the community

Ensuring that their highest administrative positions are filled with a majority of board members who uphold a hybrid orientation is an important task for Banco Palmas, whose board is formed almost entirely of local inhabitants, either clients or staff members. This structure guarantees that the beneficiaries of the MFI have an active voice in the determination of its policies. The beneficiaries identify themselves with the community bank and have no financial background or experience that might motivate the financialization of the organization. However, there are two exceptions, i.e., two internal junior managers who were trained in financial matters are employed to keep the MFI running. Although these managers are not key actors on the board, their technical perspective contributes to the balance of its hybrid mission.

Our ’board’ is all composed by local inhabitants, including employees, clients, local leaders, etc. Over 90% of the employees of Banco Palmas are local inhabitants. So, this community bank is the community and it is controlled by the community... People from outside have very little participation in our strategic decisions

Interview P6

There are other types of actors present on the board of Banco Palmas, including the leader of the organization itself, as well as politicians and representatives of civil society who are in charge of positions and activities that may be of potential interest to the community bank. There is always the risk that they might steer the organization towards financialization or political exploitation rather than remaining true to local community interests. To decrease the possibility of this occurring, the MFI’s deliberative boards are composed of an absolute majority of people who have actively participated in the history of the organization and, therefore, maintain a deep social and emotional investment in it.

Source 3: Internal operations

Strategy 5: Leadership

To decrease the risk of financially minded managers subverting the organization’s orientation, Banco Palmas relies on a development-oriented leader with a history of commitment to social improvement and community organization. Interviewee 2, the leader of Banco Palmas, has been a community organizer for many years. After leaving the Catholic Seminary in the 1980s, he took the lead in the Palmeiras community, which, at the time, was just a small group of people living in extreme misery. By relying specifically on this style of leadership, Banco Palmas strengthened its hybrid orientation through the diffusion of its values and norms from the top down.

If the leaders and employees of the community bank do not identify themselves with their territory, with their inhabitants, with the ideology that supports what a community bank is, there is the risk that the organization leans towards commercialization

Interview P2

Strategy 6: Hiring, training and socialization of employees for a hybrid orientation

The extreme institutional context of Banco Palmas - very poor and homogeneous - is reflected in a uniform staff, composed mostly of local inhabitants with basic or no formal education. From the interviews, we learned that most of their professional orientation and abilities were acquired at this community bank. Collectivist ideas found fertile ground in a region long beaten down by poverty and destitution. The existence of a pervasive resistance against economic liberalism and of a deep sensitivity towards the locals’ situation is clear across the organization.

The massive majority of Banco Palmas employees are residents from the neighborhood. When a community bank has too many outsiders, the relationship with the local community becomes difficult

Banco Palmas, 2010, p. 14

To prevent a future takeover of the financial ideology in the organization from the bottom up, Banco Palmas developed measures to routinize the replication of their values and tenets through their hiring, training and socialization processes. The leadership of Banco Palmas has routinized the transmission of its ideology through formal structures within the MFI. The most evident example is a mandatory course for all new employees, called Community Consultants, which involves the development of the technical skills related to the MFI operation, even if a large portion of its content is ideological. The participants, who are mostly hired from within the neighborhood, learn about the nature and corollaries of a solidarity economy, fair trade, peace, culture, and democracy.

In this course [Communitarian Consultants], we explain the history of this community, and we introduce some concepts of solidarity economy. We explain that the economy is meant to serve society and not the other way around, like the capitalist market does. (Interview P6).

Source 4: Competition

Strategy 7: Expanding the portfolio of services

Banco Palmas provides a wide range of services – most of these services are concentrated within Banco Palmas facilities. Some examples that go beyond offering credit are microinsurance, the organization of local fairs, professional trainings and workshops, a common purchasing system, and cultural activities and events. The extension of these services along with other services maintained by third parties –, e.g., a small store of cell phones – in one place permanently embeds Banco Palmas within the daily lives of the people of the neighborhood.

A bank correspondent operated by a traditional bank within Banco Palmas play a major role in this context as well, as it allows locals to access essential formal banking services (e.g., use of checking and savings accounts, money transfers, etc.) that were inexistent before its inception. Both community and traditional banks profit from this strategy, known as proximity financing (Gonzalez et al., 2015). While the latter benefits “from the rich knowledge and skills that the “local proximity” of MFIs provides”, the former takes the opportunity of “creating room for the diversification of microfinance services in ways that maximize their outreach and their social impact (Gonzalez et al., 2015, p. 125). As a result, the community bank is a mandatory stop for anyone who needs to pay any bill, transfer or borrow money or buy credit for his cell phone. The central role played by the MFI in the dynamics of the neighborhood works as a strategic force in competing against formal banks.

Strategy 8: Fostering the development of “prosumers”

Banco Palmas sees each client as a ’prosumer’, which means that everyone is a potential producer and consumer. By offering credit to both local consumers and entrepreneurs, the bank aims to foster and strengthen the local economy in the neighborhood. The underlying assumption is that the Conjunto Palmeiras community will have a better chance to thrive if the local money stays local, which means that people spend their money at the same neighborhood business that employs someone from the vicinity. The creation of a local currency – called Palmas – which is accepted only in the Conjunto Palmeiras, further propelled this economic circuit.

In addition, Banco Palmas charges higher interest rates to better-off clients, who contract larger loans. Small businesses, which take up over 80% of the capital lent by the MFI but represent only 35% of its credit operations, can pay interest rates as high as 50% per year (Banco Palmas, 2012). The surplus accrued is used to cross-subsidize individual borrowers who live in severe conditions of poverty and take loans that are much smaller but impose higher operational costs on the MFI. These borrowers pay interest rates ranging from 50%[3] to 0% per year (in cases of extreme destitution). The capital generated from lending to small businesses also partially subsidizes the nonfinancial services provided by Banco Palmas.

As Banco Palmas tries to tackle other constraints surrounding its local populations, such as illiteracy, unemployment, social isolation, etc., it is clear that it follows the integrative approach (Woller and Woodworth, 2001). Unlike the minimalist approach employed by most of the for-profit MFIs, which focuses solely on the poor’s lack of liquidity (Woller and Woodworth, 2001), an integrative program addresses the multiple causes of poverty (Jayo et al., 2008), which is compatible with Banco Palmas’ mission.

Key supporting mechanism in extreme institutional contexts

We argue that to be able to implement all the cited strategies and avoid falling into the trap of bending to a financial orientation, Banco Palmas protects its mission by embedding itself within the Palmas neighborhood, which is reflected in its strategies to face regulatory, governance, internal operations and competition threats. Next, we explain how embedding within the community is a relevant mechanism to implement the strategies cited above.

The choice to maintain a not-for-profit status means that Banco Palmas is in a better position to serve the population it targets. The clientele of Banco Palmas fails, in almost every aspect, to fulfil the requirements imposed by traditional banks, and, with its flexible legal status, Banco Palmas is in a better position to attend to its social mission. With a clear vision of the community Banco Palmas wants to serve, it nonetheless proceeds with political strategies targeting government officials to improve their operation conditions. The community bank employs an additional strategy to more deeply establish itself in the heart of Conjunto Palmeiras, i.e., through governance and internal operation strategies. The board of members, leaders and employees of Banco Palmas are all native inhabitants. In this sense, the degree of identification and understanding of community needs could not be higher.

Banco Palmas is the community. There’s an organic intimacy between the local people and this organization. The bank is the offspring of the community. It’s completely different from a commercial bank that lands here and knows no one, has no history here

Interview P2

This identification between staff and clients also adds value that is not easily replicated by the competing financial MFIs, which are outsiders. Many local inhabitants actually prefer to pay higher rates on their loans because they have more trust and connections with the Palmas MFI that go beyond the financial transactions. The loan officers of Banco Palmas are the long-standing neighbors of the borrowers, with whom they typically have relational ties. Banco Palmas also promotes the awareness that it is part of the community, that it is owned by the community and that it strives for the improvement of local conditions. Conversely, the financial MFIs operating in the area are seen as external agents exploiting the local population for profit.

Such a degree of embeddedness benefits Banco Palmas by giving it more and better-quality information about the borrowers (a higher level of information symmetry) by establishing informal (social) systems of reward and punishment that can be used in enforcement activities against defaulters and by increasing the level of trust among clients and loan officers.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, we contribute to the literature on the sustainability of hybrid organizations by extending the knowledge on strategies to avoid mission drift in extreme contexts. Our findings advance the current literature on two fronts. First, we reveal a series of strategies that can be adopted by hybrid organizations to respond to pressures of mission drift. Second, we argue that by developing the mechanism of embedding within local communities, hybrid organizations may increase their chances of becoming sustainable over time.

Extending the knowledge on mission drift avoidance

Our study provides a comprehensive and empirical view of mission drift and the tangible strategies that can be mobilized by hybrid organizations in the microfinance industry to avoid it. The previous empirical studies on how to avoid mission drift tend to focus on one or a few antecedents to mission drift and, consequently, suggest isolated approaches to combat mission drift. Examples include the design of incentives to credit agents (Aubert et al., 2009), policies for recruiting, training and socialization (Battilana and Dorado, 2010), board composition (Hartarska and Mersland, 2012) and the reduction of operational costs (Serrano-Cinca, Gutiérrez-Nieto, 2014). Our paper acknowledges – as, theoretically, do Jones (2007) and Cornforth (2014) – the reality that hybrid organizations are subjected to multiple pressures towards financialization, which, therefore, must be counteracted through multiple strategies.

We make use of a concrete case to describe how hybrid MFIs engage in strategies to avoid mission drift. In particular, we identify four sources of missions drift (regulatory challenges; sources of funding and governance; internal operations; and competition) and eight strategies to avoid these sources (operating as not-for-profit; supporting the institutionalization of community banks; safeguarding the ownership and control of the organization; composing a board with members of the community; leadership; hiring, training and socializing employees towards a hybrid orientation; expanding the portfolio of services; and fostering the development of “prosumers”).

It is worth noting that some of the strategic actions mobilized by Banco Palmas produced outcomes that contradict some of the mission drift literature. Regarding the composition of the board, Harstarska and Mersland (2102) found that the presence of donors, workers and CEOs on the board negatively affects the financial and social performance of MFIs. Banco Palmas’ board is composed with these types of individuals. Nonetheless, board members do not report problems in this regard. We suspect that the conjunction of the other strategic actions focused on the avoidance of mission drift have neutralized the risk imposed by boards with such a configuration. Another possibility is that these boards actually hurt the performance of the MFIs in an indirect fashion that can be difficult for those external to the organization to visualize.

Regarding hiring, training and socializing, other Bolivian MFI BancoSol failed to secure its hybrid mission because it adopted an ’integration strategy’ for recruiting and socializing its personnel (Battilana and Dorado, 2010). This organization hired employees who already had a professional background either in finance or social work. When trying to socialize the employees into a hybrid ideology, major conflicts arose among them, which ended up undermining the integrity of the MFI’s mission. Banco Palmas has partially adopted an integration strategy; however, it has done so with success. Some of the employees of Banco Palmas come from either the financial sector or the development field. These employees are socialized into the hybrid ideology only after being recruited by the MFI, just as BancoSol did in the past. We conjecture that a visible trait of Banco Palmas’ workers may be the reason why it succeeded in securing a hybrid ideology among them. The individuals with a financial background possess banking expertise; however, they are openly critical of the banking sector, as we show in the results section. It is possible that their disillusion with their previous jobs in the financial sector prompted them to be cautious when using their knowledge in a hybrid organization. Overall, Banco Palmas’ case shows that an integration strategy can be successful.

It is also interesting to note that some of the sources of mission drift that are presented in the context of Banco Palmas have proved not to affect its hybridity. Coopestake (2007a, 2007b) asserts that the hybrid missions of MFIs that do not systematically monitor their social and financial performance are at risk. Aubert et al. (2009) claim that the metrics used to reward the performance of credit agents can also lead to mission drift, especially if the incentives are focused on the financial aspects of the loans. In fact, Banco Palmas has simple management practices that do not follow the traditional methods of accounting to monitor and assess its performance, and its credit agents do not receive any type of formal performance incentive. Even so, it has not drifted away from the hybrid ideology.

In a recent study with 405 MFIs in Latin America between 2005 to 2014, authors found that type of ownership affected the orientation for better financial versus social performance. Bank-type MFIs are more likely to be related with attracting better off clients instead of reaching to the poor, in opposition to NGO-type MFIs that do not prioritize financial performance (Amin et al., 2018). Banco Palmas decided to maintain its NGO status, even though it manages to design products for better-off clients. Perhaps a combination of Banco Palmas’ NGO status with its geographical targeting that acts as a deterrent to mission drift. The area served by the Brazilian MFI is one of the poorest in the country. In this extreme context, it would actually be more difficult for the MFI to focus solely on richer clients simply because they are too few.

The importance of embedding within the community in extreme institutional contexts

Our study also contributes to the branch of the microfinance literature that investigates the effects of various context-dependent elements on MFIs (e.g., Johnson, 1998; Bhatt & Tang, 1998; Bruton et al., 2011; Elahi & Danopoulos, 2004; Woller & Woodworth, 2001; Churchill, 1999; Marconatto et al., 2013; Boehe & Barin-Cruz, 2013). We argue that embedding within the community represents a key mechanism to avoid mission drift, particularly in extreme contexts. Banco Palmas identifies with its target communities to such a high degree that it builds relationships of trust that are difficult for traditional banks to replicate. Therefore, embeddedness becomes a competitive advantage that also prevents financialization. Scholars have long discussed the benefits of embeddedness for organizations and individuals (e.g., Coleman, 1988; Granovetter, 1985, 2005), a benevolence that can be used to facilitate collective action (Adler & Kwon, 2002). Our study goes a step further and suggests this mechanism as a strategy for avoiding mission drift, responding to pressures coming from different levels.

However, embeddedness is unlikely to be a strategy that can be immediately mobilized by all hybrid businesses under the threat of mission drift. It takes time for organizations to entrench themselves into their local contexts. The process requires identification, trust and other elements that need time to blossom into reality. In other words, embeddedness can be promptly used only by organizations that are already embedded within their communities.

This phenomenon seems to be the case of community-based enterprises (CBEs) emerging out of poor localities as a response to some social or environmental distress (Peredo & Chrisman, 2006). As CBEs are created and managed by local individuals and for local individuals, are run on available community skills and are heavily dependent on community participation (Peredo & Chrisman, 2006), they are locally embedded from inception. Thus, organizations that share some of the characteristics of CBEs (e.g., dependency on community social capital and the pursuit of multiple objectives to simultaneously achieve social, economic, environmental communitarian goals) should be better equipped to use embeddedness as a strategy to deter mission drift.

Hybrid organizations that do not yet have a high level of identification with their context will have to resort to other strategic options if they want to harness the benefits of embeddedness in the struggle against mission drift. One example is the development and use of native capabilities, a competence that allows organizations to mobilize resources that are intrinsic to the communities they serve (Hart & London, 2005; Hart, 2005). Native capabilities imply the ability to create a web of trustworthy relationships with nontraditional partners (e.g., informal actors) to understand, leverage, and build on existing social networks (London and Hart, 2004). This competence tends to produce effects that are similar to those of embeddedness. Although it also requires time to develop, this approach may obtain results in a shorter period of time. While embedding in a community is a historic process, the native capability is developed through direct actions, such as engaging nontraditional partners, co-creating local solutions, developing local expertise, and building social contracts (Hart & London, 2005). Marconatto, Barin-Cruz, Pozzebon & Poitras (2016a) showed how a multinational organization developed its native capability in a rather short period of time to develop a successful project within a poor Brazilian community.

Finally, we suggest that researchers continue to develop future studies involving hybrid MFIs in as-yet understudied contexts (e.g., communist or transitional countries). These future studies could enhance and extend the perspective developed in this work. The market values and financial norms of these countries, and the manner in which these factors affect their economies, are profoundly different from those of Western countries (Peng, 2003). Such dissimilarities among ideological orientations may reveal additional sources of mission drift and identify new strategies for its prevention.

Furthermore, we encourage researchers to explore different theoretical perspectives from which to approach the causes and consequences of mission drift and the strategies to avoid it. Critical theory and social constructivism, for example, may offer new viewpoints for scholars and practitioners who are engaged in the preservation of the original mission of microfinance.

Parties annexes

Biographical notes

Diego Marconatto is Associate Professor at Unisinos Business School (Unisinos University). He holds a PhD from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) and has worked as a postdoc researcher at HEC Montréal (Canada) and at Universidad de Sevilla. Currently, Prof. Diego teaches entrepreneurship and business performance. His main research interests are small business growth and entrepreneurship. Formerly, he has published many papers on microfinance and hybrid organizations. Before his academic career, he has worked as Logistics executive manager and business consultant.

Luciano Barin Cruz is Professor of Management and Sustainability at HEC Montréal, Canada. He is the Director of Pôle Ideos (social enterprise centre) at HEC Montreal and the Director of the Yunus Social Business Centre (HEC Montreal). He currently works in a major project aiming reinforcing the managerial capabilities of social enterprises in Quebec (Maison de l’innovation social – MIS). His research projects focus on sustainability, social responsibility and social innovation and they have been published in journals such as Journal of Management Studies, Organization, World Development, Business & Society, Journal of Business Ethics, Management Decision, Journal of Cleaner Production, among others.

Natalia Aguilar Delgado is Assistant Professor of International Business at HEC Montreal. She received her Ph.D. in Management (Strategy and Organization) from McGill University. Her research is published in Business & Society, Journal of Organizational Ethnography, RAE, among others. Her research interests include transnational governance, international development, community organizations, and inclusive value chains.

Notes

-

[1]

The group lending method has been object of contradictory appraisals. Advocates would argue that this is a way for turning poor people into bankable individuals (Yunus, 2007). Critiques, on the other hand, would point out that, in the longer term, the ’harvesting’ of an individual’s social capital is actually bad for the poor because it increases their vulnerability, pushing households into unsustainable debt (Bateman et al., 2018). Also, as Armendariz and Morduch (2007) point out that although the benefits of group lending in transferring responsibilities and costs from bank staff to borrowers, the use of social sanctions to encourage participation has its limits (e.g. small village communities in which people are very close friends or family; urban areas where borrowers barely know each other).

-

[2]

AICESIS stands for ’International Association of Economic Counsels and Similar Institutions’.

-

[3]

This rate may seem exorbitant, but it is considered low for the Brazilian context, where consumers pay an average interest rate of over 90% per year to traditional banks.

Bibliography

- Abramovay, Ricardo; Junqueira, Rodrigo Gravina P. 2005.A sustentabilidade das microfinanças solidárias. Revista de Administração da Universidade de São Paulo (RAUSP), São Paulo, Vol. 40, No1, p. 19-33, jan./fev./mar.

- Adler, P. S. and S.-W. Kwon, (2002). “Social Capital: Prospects for a New Concept”, Academy of Management Review, 27(1), p. 17.

- Almandoz, J. (2012). “Arriving at the starting line: The impact of community and financial logics on new banking ventures,” Academy of Management Journal, 55(6): p. 1381-1406.

- Alves, S., & Soares, M. (2006). Microfinanças. Democratização do crédito no Brasil. Atuação do Banco Central. Brasília: BCB.

- Amin, W., Qin, F., Ahmad, F., & Rauf, A. (2018). Ownership Structure and Microfinance Institutions’ Performance: A Case of Latin America. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences, 7(1), p. 127.

- Arena, T. (2009). “Social corporate governance and the problem of mission drift in socially-oriented microfinance institutions,” Columbia Journal of Law & Social Problems, 41(3), p. 269-316.

- Armendáriz, B. and J. Morduch, (2007). The economics of microfinance. Cambridge, England: The MIT Press.

- Ashforth, B. E. and P. H. Reingen, (2014). “Functions of dysfunction: Managing the dynamics of an organizational duality in a natural food cooperative,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 59(3), p. 474-516.

- Aubert, C., A. de Janvry and E. Sadoulet, (2009). “Designing credit agent incentives to prevent mission drift in pro-poor microfinance institutions,” Journal of Development Economics, 90(1), p. 153-162.

- Austin, J., Stevenson, H., and J. Wei‐Skillern, (2006). “Social and commercial entrepreneurship: same, different, or both?” Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 30(1), p. 1-22.

- Banco Palmas. (2010). Banco Palmas – 100 perguntas mais frequentes. Fortaleza: Instituto Palmas.

- Banco Palmas. (2012). História do Conjunto Palmeiras. Retrieved January 17, 2014, from http://www.bancopalmas.org.br/oktiva.net/1235/secao/14723.

- Bastiaensen, J., P. Marchetti, R. Mendoza and F. Pérez, (2013). “After the Nicaraguan Non‐Payment Crisis: Alternatives to Microfinance Narcissism,” Development and Change, 44(4): p. 861-885.

- Bateman, M. (2018). Small loans big problems: the rise and fall of microcredit as a development policy. Handbook on Development and Social Change, p. 131.

- Bateman, M., Blankenburg, S., & Kozul-Wright, R. (Eds.). (2018). The rise and fall of global microcredit: development, debt and disillusion. Routledge.

- Battilana, J. and S. Dorado, (2010). “Building sustainable hybrid organizations: the case of commercial microfinance organizations,” Academy of Management Journal, 56(6), 1419-1440.

- Battilana, J., M. Lee, J. Walker and C. dorsey, (2012). “In search of the hybrid ideal,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, 10(3), p. 50-55.

- Battilana, J., M. Sengul, A. C. Pache and J. Model, (2015). “Harnessing productive tensions in hybrid organizations: The case of work integration social enterprises,” Academy of Management Journal, 58(6), p. 1658-1685.

- Beisland, L. and R. Mersland, (2012). “An analysis of the drivers of microfinance rating assessments,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(2), p. 213-231.

- Berger, Marguerite. (2006).”The Latin American model of microfinance.” In: Berger, Marguerite, Lara Goldmark, and Tomás Miller Sanabria. An inside view of Latin American microfinance. IDB, p. 1-36.

- Bhatt, N. and S. Y. Tang, (1998). “The problem of transaction costs in group-based microlending: an institutional perspective,” World Development, 26(4), p. 623-637.

- Bruton, G. D., S. Khavul and H. Chavez, (2011). “Microlending in emerging economies: building a new line of inquiry from the ground up,” Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), p. 718-739.

- Boehe, D. M. and L. Barin-Cruz, (2013). “Gender and Microfinance Performance: Why Does the Institutional Context Matter?” World Development, 47, p. 121-135.

- Bouchard, M. J., & Michaud, V. (2015). La politique d’achat d’une coopérative de solidarité en environnement. Revue française de gestion, (1), p. 143-158.

- Business Insider. (2012, February 24). Hundreds of suicides in India linked to microfinance organizations. Feb 24th. Business Insider. Retrieved November 10, 2016, from http://www.businessinsider.com/hundreds-of-suicides-in-india-linked-to-microfinance-organizations-2012-2.

- Choi, C. J., S. W. Kim and J. B. Kim, (2009). “Globalizing business ethics research and the ethical need to include the bottom-of-the-pyramid countries: redefining the global triad as business systems and institutions,” Journal of Business Ethics, 94(2), p. 299-306.

- Churchill, C. F. (1999). Client focused lending: the art of individual lending. Toronto, Canada: Calmeadow.

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). “Social capital in the creation of human capital,” American Journal of Sociology, 94(1), p. 95-120.

- Copestake, J. (2007a). “Mainstreaming microfinance: social performance management or mission drift?” World Development, 35(10), p. 1721-1738.

- Copestake, J. (2007b). “Mission drift - Understand it, avoid it,” Journal of Microfinance, 9(2), p. 20-25.

- Corbin, J. and A. Strauss, (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. London, England: Sage Publications.

- Cornforth, C. (2014). “Understanding & combating mission drift in social enterprises,” Social Enterprise Journal, 10(1), p. 3-20.

- Cull, R., A. Demirgüç-Kunt and J. Morduch, (2007). “Financial performance and outreach: a global analysis of leading microbanks,” The Economic Journal, 117(517), F107-F133.

- Cull, R., A. Demirgüç-Kunt and J. Morduch, (2009a). “Microfinance meets the market,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(1), p. 167-192.

- Cull, R., A. Demirgüç-Kunt and J. Morduch, (2009b). Microfinance tradeoffs: regulation, competition, and financing (Policy Research Working Paper 5086). Washington: The World Bank Development Research Group Finance and Private Sector Team.

- Dattasharma, A., R. Kamath, and S. Ramanathan, (2015). “The Burden of Microfinance Debt: Lessons from the Ramanagaram Financial Diaries,” Development and Change, 47(1): p. 130-156.

- Doherty, B., Haugh, H. and F. Lyon, (2014). “Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda,” International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(4), p. 417-436.

- Ebrahim, A., Battilana, J. and J. Mair, (2014). “The governance of social enterprises: mission drift and accountability challenges in hybrid organizations,” Research in Organizational Behavior, 34, p. 81-100.

- Elahi, K. Q. and C. P. Danopoulos, (2004). “Microcredit and the third world: perspectives from moral and political philosophy,” International Journal of Social Economics, 31(7), p. 643-654.

- Ella. (2013). Guide to Microfinance in Latin America [Online]. Available: http://ella.practicalaction.org/knowledge-guide/guide-to-microfinance-in-latin-america/ [Accessed 2019].

- Epstein, M. J. and K. Yuthas, (2010). “Mission impossible: diffusion and drift in the microfinance industry,” Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 1(2), p. 201-221.

- FrançaFilho, G. C., SilvaJúnior, J. T. and Rigo, A. S. (2012). Solidarity finance through community development banks as a strategy for reshaping local economies: lessons from Banco Palmas. Revista de Administração, 47(3), p. 500-515.

- Getu, M. (2007). “Does commercialization of microfinance programs lead to mission drift?” Transformation, 24(3), p. 169-180.

- Gonzalez, L., Diniz, E. H., & Pozzebon, M. (2015). “The value of proximity finance: how the traditional banking system can contribute to microfinance”. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 10(1-2), p. 125-137.

- Granovetter, M. (1985). “Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness,” American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), p. 481-510.

- Granovetter, M. (2005). “The impact of social structure on economic outcomes,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(1), p. 33-50.

- Hart, S.L., (2005). Capitalism at the Crossroads; the Unlimited Business Opportunities in Solving the World’s Most Difficult Problems. Wharton School Publication, Upper Saddle River, 304 pp.

- Hart, S.L. and T. London, (2005). “Developing native capability,” Stanford Soc. Innov. Rev. Summer 2005, p. 28-33.

- Hartarska, V. and R. Mersland, (2012). “Which governance mechanisms promote efficiency in reaching poor clients? Evidence from rated microfinance institutions,” European Financial Management, 18(2), p. 218-239.

- Hartarska, V. and D. Nadolnyak, (2008). “Does rating help microfinance institutions raise funds? Cross-country evidence,” International Review of Economics & Finance, 17(4), p. 558-571.

- Hudon, M. and J. Sandberg (2013). “The ethical crisis in microfinance: Issues, findings, and implications,” Business Ethics Quarterly, 23(4): p. 561-589.

- Hung, C. R. (2006). “Rules and Actions: Determinants of Peer Group and Staff Actions in Group-Based Microcredit Programs in the United States,” Economic Development Quarterly, 20(1), p. 75-96.

- Instituto Palmas. (2011). Quadro geral - Números 2011. Retrieved February 20, 2013, from http://www.inovacaoparainclusao.com/nuacutemeros.html.

- IPEA. (2016). Os Novos Dados do Mapeamento de Economia Solidária no Brasil: notas metodológicas e análise das dimensões socioestruturais dos empreendimentos. Brasília, Brazil: Governo Federal.

- IPECE. (2014). Pobreza em Fortaleza. IPCE. Retrieved March 10, 2015, from http://www.ipece.ce.gov.br/noticias/ipece-na-midia/mais-de-130-mil-pessoas-vivem-na-extrema-pobreza-1

- Jayo, M., Pozzebon, M., & Diniz, E. H. (2009). “Microcredit and innovative local development in Fortaleza, Brazil: the case of Banco Palmas”. Canadian Journal of Regional Science, 32(1), p. 115.

- Johnson, S. (1998). “Microfinance north and south: contrasting current debates,” Journal of International Development, 10(6), p. 799-810.

- Jones, M. B. (2007). “The multiple sources of mission drift,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(2), p. 299-307.

- Kent, D. and M. T. Dacin, (2013). “Bankers at the gate: microfinance and the high cost of borrowed logics,” Journal of Business Venturing, 28(6), p. 759-773.

- Khavul, S. (2010). “Microfinance: Creating opportunities for the poor?” Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(3): p. 58-72.

- Ledgerwood, J. and V. White, (2006). Transforming microfinance institutions: providing full financial services to the poor. New York, USA: World Bank Publications.

- London, T. and S.L. Hart, (2004). “Reinventing strategies for emerging markets: beyond the transnational model,” Journal International Business Studies. 35 (5), p. 350-370.

- Mair, J. and I. Marti, (2006). “Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight,” Journal of world business, 41(1), p. 36-44.

- Mair, J., J. Mayer and E. Lutz. (2015). “Navigating institutional plurality: Organizational governance in hybrid organizations,” Organization Studies 36(6): p. 713-739.

- Maîtrot, M. (Forthcoming 2018). “Understanding Social Performance: A ’Practice Drift’ at the Frontline of Microfinance Institutions in Bangladesh,” Development and Change. p. 1-32.

- Marconatto, D. (2013). A influência das três forças sociais sobre as atividades de avaliação, monitoramento e enforcement executadas por instituições de microfinança socialmente orientadas de empréstimos individuais em um país desenvolvido e em um país em desenvolvimento. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Lume Database. http://hdl.handle.net/10183/77140

- Marconatto, D., L. Barin-Cruz and E. AvilaPedrozo, (2016a). “Going beyond microfinance fuzziness,” Journal of Cleaner Production, 115, p. 5-22.

- Marconatto, D., L. Barin-Cruz, M. Pozzebon and J. Poitras (2016b). “Developing sustainable business models within BOP contexts: mobilizing native capability to cope with government programs,” Journal of Cleaner Production, 129, p. 735-748.

- Marconatto, D. A. B., Cruz, L. B., Moura, G. L., & Teixeira, E. G. (2017). Why Microfinance Institutions Exist: Lending Groups as a Mechanism to Enhance Informational Symmetry and Enforcement Activities. Organizações & Sociedade, 24(83), p. 633-654.

- Marconatto, D. A. B., L. Barin-Cruz, R. Legoux and D. C. Dantas, (2013). “Microfinance in Latin America and the Caribbean: The influence of territory on female repayment performance in a polarized region,” Management Decision, 51(8), p. 1596-1612.

- McDonald, S. (2005). “Studying actions in context: a qualitative shadowing method for organizational research,” Qualitative Research, 5(4), p. 455-473.

- Mersland, R. and R. Ø. Strøm, (2010). “Microfinance mission drift?” World Development, 38(1), p. 28-36.

- Miles, M. B. and A. M. Huberman (1994). Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, USA: Sage Publications.

- Mix Market. (2003). Benchmarking Latin American Microfinance. Available at: https://www.findevgateway.org/sites/default/files/publication_files/mix_2003_latin_america_caribbean_benchmarking_report_en_0.pdf

- Morduch, J. (2000). “The microfinance schism,” World Development, 28(4), p. 617-629.

- Pache, A.-C. and F. Santos (2010). “When worlds collide: The internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands,” Academy of management review, 35(3): p. 455-476.

- Pache, A.-C. and F. Santos (2013). “Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics,” Academy of Management Journal, 56(4): p. 972-1001.

- Peng, M. (2003). “Institutional transitions and strategic choices,” Academy of Management Review, 28(2), p. 275-296.

- Peredo, A. M. and J. J. Chrisman, (2006). “Toward a theory of community-based enterprise,” Academy of Management Review, 31(2), p. 309-328.