Résumés

Abstract

This research investigates the main motivations driving China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) in France and the management style that Chinese companies adopt toward their French subsidiaries. On the basis of interviews with managers of 17 Chinese subsidiaries in France, the authors identify sales in French and European markets as the main driver of Chinese FDI in France. Chinese FDI in France also aims at building bridges to African markets. The second FDI motive is asset seeking. For managing their subsidiaries in France, the Chinese companies adopt a polycentric management style. The Chinese parent companies rely on French managers, while Chinese expatriates adopt observational attitudes. This research confirms that the Chinese government is closely involved in Chinese outward FDI and supports both the “linkage, leverage, and learning” perspective and springboard theory.

Keywords:

- Chinese Foreign Direct Investment,

- FDI Motivations,

- Chinese management style,

- France,

- Interviews

Résumé

Cette recherche examine les principales motivations des investissements directs étrangers (IDE) chinois en France ainsi que le style de gestion que les entreprises chinoises adoptent envers leurs filiales françaises. Sur la base d’entretiens avec des managers de 17 filiales chinoises en France, les auteurs identifient les ventes sur les marchés français et européens comme le principal moteur des IDE chinois en France. Les IDE chinois en France visent également à établir des ponts vers les marchés africains. Le deuxième motif de l’IDE chinois est la recherche d’actifs stratégiques. Pour la gestion de leurs filiales en France, les sociétés chinoises adoptent un style de management polycentrique. Les sociétés mères chinoises s’appuient sur des managers français, tandis que les expatriés chinois adoptent des attitudes d’observation. Cette recherche confirme que le gouvernement chinois est étroitement impliqué dans l’IDE chinois et soutient à la fois la théorie « Association, Levier et Apprentissage » et la théorie du tremplin.

Mots-clés :

- Management international,

- Multinationales chinoises,

- Investissements directs étrangers,

- Gestion des filiales,

- France

Resumen

Esta investigación examina las principales motivaciones de la inversión extranjera directa (IED) de China en Francia y el estilo de gestión que las empresas chinas adoptan hacia sus filiales francesas. Sobre la base de entrevistas con los gerentes de 17 filiales chinas en Francia, los autores identifican las ventas en los mercados francés y europeo como el principal impulsor de la IED china en Francia. La IED china en Francia también tiene por objeto tender puentes hacia los mercados africanos. El segundo motivo de la IED china es la búsqueda de activos estratégicos. Para la gestión de sus filiales en Francia, las empresas chinas adoptan un estilo de gestión policéntrico. Las empresas matrices chinas confían en los directivos franceses, mientras que los chinos expatriados adoptan actitudes de observación. Esta investigación confirma que el gobierno chino está estrechamente involucrado en la salida de IED china y apoya tanto la teoría de la “Linkage, Leverage, Learning” como la teoría del trampolín.

Palabras clave:

- Gestión internacional,

- Empresas multinacionales chinas,

- Inversión extranjera directa,

- Gestión de filiales,

- Francia

Corps de l’article

Introduction

According to the World Investment Report (UNCTAD, 2017), in 2016, China rose to the position of the second-largest source of outward foreign direct investment (FDI). FDI outflows from China increased 44% in one year to 183 billion U.S. dollars whereas China’s FDI outflows were 36% more than the amount of its inflows. In Europe, the absolute value remains small yet the numbers have increased rapidly, establishing the continent as the most rapidly growing destination for Chinese FDI. Hanemann and Huotari (2016) report that Chinese FDI in Europe hit a new high record in 2015 and that China’s global investment boom is unlikely to end any time soon. They underline that Europe has emerged as a main destination for Chinese FDI, in line with a broader shift of Chinese investment from developing and emerging to high-income economies. Within Europe, France is with Germany and the UK, one of the big three recipients of Chinese FDI, attracting 16% of Chinese projects in Europe (AFII, 2015).

The last decade, academic research contributed to a better understanding of Chinese FDI motivations, in general (Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Buckley et al., 2007; Rui and Yip, 2008; Amighini et al., 2011; Kolstad and Wiig, 2012; Peng, 2012; Deng, 2013; Yin, 2015; Luo and Zhang, 2016) and in Europe (Minin and Zhang, 2010; Clegg and Voss, 2011; Zhang et al., 2013; Dreger et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2016). However, no researches consider Chinese FDI motivations in France explicitly nor address the management styles and practices that Chinese companies adopt, after foreign acquisitions.

To fill this gap, we have interviewed Chinese and French managers of 17 Chinese subsidiaries in France with a double research objective. First, we seek to deepen understanding of the motivations of Chinese companies that invest in France. In the past decade, quantitative research has offered some macroeconomic conclusions about the reasons for outward Chinese FDI, but a lack of qualitative, empirical research exists to explicate the underlying motives for Chinese firms to invest in advanced economies such as France. Second, related to their FDI motivations, our research investigates the management style and practices that the Chinese firms adopt after acquiring a subsidiary in France. Only a very few academic empirical researches (Fan et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014) have explored this question.

The findings reveal that Chinese companies pursue two complementary goals when investing in France. First, market-seeking Chinese companies want to increase their sales on French and European markets, as well as on French-speaking African markets or to compete back on the Chinese market. Second, asset-seeking Chinese companies want to improve their global competitiveness by acquiring strategic assets, including industrial technology, advanced production methods, R&D capabilities, international recognized brands and international managerial skills. Regarding our second research objective, we find that Chinese companies show a polycentric management style, such that they rely on local, French and European, managers and engineers to manage their subsidiaries in France. Chinese expatriate managers, clearly engaged in a management learning process, adopt observational roles. Our research suggests that such polycentric management style is the consequence of the market-seeking and asset-seeking motives which the Chinese firms pursue with their acquisitions in France.

Our empirical research results contribute to reverse FDI theory in several ways. First, we find that Chinese FDI in developed countries has both market-seeking and asset-seeking motives. Second, we confirm the “linkage, leverage, and learning” perspective proposed by Mathews (2002, 2006). Third, we see one case that fits the “springboard theory” (Luo and Tung, 2007). Fourth, our sample shows that many Chinese firms, both private and state-owned, receive direct or indirect support from the Chinese authorities, leading to “government-created advantages” (Ramamurti and Hillemann, 2017), which enhance FDI of Chinese firms with relatively few prior international experience (Wang et al., 2014). Fifth, our research offers a new theoretical lens to look at Chinese FDI in Europe, we call the “bridging theory”. Some Chinese firms acquire French firms with the aim of building a bridge to West-African markets, which have strong historical ties with France. Thanks to the distribution networks and knowledge about African markets of their subsidiaries in France, Chinese multinationals seek to enhance their sales on those French-speaking African markets.

Moreover, our empirical research contributes to the international management theory. In line with Miedtank (2017, p. 89), stating that “Chinese companies have adopted a ‘light-touch’ or ‘hybrid’ approach toward managing their European subsidiaries”, Fan et al (2013) and Shen and Edwards (2006), we found that Chinese firms, after acquiring subsidiaries in France, adopt a polycentric management style, relying on local French managers while Chinese expatriates adopt an observational attitude. Like Wang et al. (2014), we find that Chinese headquarters grant substantial management autonomy to their subsidiaries in France. We advance four explanations for such “Chinese” management attitude.

First, market-seeking Chinese firms lack knowledge of French and European markets. Second, asset-seeking Chinese companies need to maintain French engineers and technicians and integrate their technological knowledge in the value chain of the Chinese multinational. Third, most of the Chinese firms investing in France, which are rather young and undergo a quick internationalization process lack international management experience. Fourth, Chinese firms want to avoid cross-cultural misunderstanding and mistakes that might hinder the development of their subsidiaries in France.

Agreeing with Luo and Zhang, (2016, p. 343) that “developed market-based FDI theories cannot adequately explain international expansion of emerging markets multinational enterprises”, we first consider in the next section the main “reverse” FDI theories. Then we review the main FDI motivation taxonomies and consider the key characteristics of Chinese FDI. After, we explain our qualitative research methodology and describe the sample of Chinese subsidiaries in France. In answering our research questions, we first detail the Chinese companies’ motivations to invest in France and second analyze the management style they adopt after acquiring a subsidiary in France. In doing so, sharing Luo and Zhang’s (2016, p. 338) belief “that more qualitative research [...] can bring more insightful observations about the international process and strategic behaviour of emerging market MNEs”, we answer Ramamurti and Hillemann’s (2017) call for “more thick descriptions and grounded research of Chinese MNEs”. This article concludes with a discussion of our research findings and its implications.

Literature review

To emphasize our research goal and questions, leading to our empirical approach, we review in this section successively reverse FDI theory, FDI motivation taxonomies and the main characteristics of Chinese FDI.

Reverse FDI

Increasing FDI comes from emerging countries and flows to industrialized countries. Traditional international investment theories cannot explain such reverse FDI, because emerging country MNCs show essential differences from MNCs in developed countries. For example, Chinese MNCs cannot be compared with MNCs from developed countries, because they tend to initiate FDI quickly, even without monopolistic or OLI advantages nor any international experience (Ramamurti and Hillemann, 2017). Therefore, in order to remedy the lack of theory explaining emerging countries FDI, academic research developed reverse FDI theory, of which the most representative are the localized technological innovation theory (Lall, 1984), the role of home country governments (Buckley et al., 2007; Peng, 2012), the “linkage, leverage, and learning” perspective (Mathews, 2002, 2006), as well as the springboard theory (Luo and Tung, 2007).

Lall’s (1984) developed the localized technological innovation theory. He shows empirically that FDI from developing nations is not necessarily confined to low-technology, small-scale, and labor-intensive production. Through technology accumulation, competitive advantages can evolve (Lall, 1984). Developing countries’ companies might have abilities to absorb foreign technical knowledge or to meet the needs of local consumers. After an imitation stage, these companies also can improve the absorbed foreign technology and sometimes become highly innovative. This theoretical approach gives an asset-seeking explanation for why emerging country firms invest: they have accumulated a certain level of technological advantages, and they are looking for supplementary technological resources in industrialized nations.

As a variant of this localized technological innovation idea, Mathews (2002, 2006) asserts that the latecomer disadvantages suffered by emerging country MNCs can be transformed into a source of competitive advantage, through linkage, leverage, and learning. In the linkage stage, the latecomer firm links, through outward FDI and strategic alliances, with leading international firms in industrialized countries. In the leverage stage, this emerging country firm turns its newly acquired resources into opportunities, using them to upgrade its technology and diversify its product portfolio. Through learning, the emerging country MNC increases its technological capabilities and accesses new opportunities through repeated linkage, leverage, and learning processes, evolving toward higher value-added market segments. Recently, Thite et al. (2016), adopting the linkage, leverage and learning perspective, show how four Indian multinationals have evolved themselves to become credible global players by leveraging on their learning through targeted acquisitions in developed markets to acquire intangible assets and/or following global clients in search of new markets and competitive advantages. This theory offers a promising rationale for Chinese FDI in France.

Researchers also note the role of developing country governments in FDI decisions by enterprises of that country (Buckley et al., 2007; Peng, 2012). For example, the Chinese government uses policy tools such as low-interest financing, favorable exchange rates, reduced taxation, and subsidized insurance for expatriates to encourage FDI. Chinese firms have responded to these institutional incentives by venturing abroad (Peng, 2012). Ren et al. (2012) confirm that the Chinese government has implemented economic policies that help Chinese firms get cheaper bank loans to support their cross-border investments. These “government-created advantages” have complemented China’s natural endowments and significantly improved Chinese MNEs international competitiveness (Ramamurti and Hillemann, 2017).

Luo and Tung (2007) suggest that emerging country MNCs use international expansion as a “springboard” and acquire critical resources to compete more effectively against global rivals, both at home and on foreign markets. Springboarding might be a deliberate, long-range strategy to establish competitive positions more solidly in the global marketplace. Luo and Tung (2007) list several behaviors or activities typical of a springboard strategy. First, companies seek sophisticated technology or advanced manufacturing know-how. Second, they try to overcome latecomer disadvantages related to their consumer base, brand recognition, or technological leadership. Third, springboarding MNCs seek to counterattack global rivals at home, avoid trade barriers, and reduce domestic constraints. Such strategies also encourage Chinese MNCs to acquire critical assets from companies in mature countries, through mergers and acquisitions. A springboard approach also might be encouraged by national governments, which is confirmed by our Chinese sample in France.

FDI motivation

Our first research question is to determine the motivations of Chinese firms to do direct investments in France. Makino et al. (2002, p. 404) define an FDI motivation as the reason that gives an investing firm the impetus for investing abroad. Dunning and Lundan (2008, p. 63), define FDI motivation more simply as “the reasons prompting firms to undertake FDI”. Firms invest abroad for many different reasons[1]. Building on Dunning’s initial taxonomy, Dunning and Lundan (2008), point out four main reasons for a firm to undertake, what they call, “foreign value added activities” (op. cit., p. 63). First, resource seeking firms look overseas for resources of better quality and/or lower costs, of three types: physical resources, cheap, well-motivated, semi- and unskilled labour as well as technological and/or management expertise. Second, market seeking firms protect existing foreign markets, promote new markets or have to follow main order-givers. Their direct investment is motivated by the wish to adapt goods and services closer to local consumers, the search for lower production or transportation costs in host countries, the choice to be strategically present in key-markets or by advantages offered by host country governments. Third, efficiency seekers rationalize geographical dispersed activities in a given region through relocating in host countries with low factor costs and regrouping activities in search for economies of scale or scope. Last, strategic asset seekers pursue long-term strategic objectives and aim at augmenting their global portfolio of assets and human competences.

Makino et al. (2002), studying the FDI location choice of 328 Taiwanese firms, distinguish asset-exploitation and asset-seeking FDI. Firms exploiting assets look for more efficient production through lower factor costs, marketing expertise or want to develop distribution channels. Asset-seeking firms acquire new or complementary assets, mostly in developed countries. The authors (op. cit., p. 414) do an empirical regression analysis, with the investment location as a dependent variable, explained by three main categories of FDI motivation: market seeking, resource seeking (i.e. low labor costs) and technology seeking. These three motivations fit Dunning and Lundan’s (2008) taxonomy. More recently, Giroud and Mirza (2015) refine the widely adopted Dunning’s FDI motivation taxonomy (i.e. market-, efficiency-, resources- and strategic asset seeking) with a series of host country characteristics, including its political stability, infrastructure, availability of skilled management and engineers’ talents, level of propriety protection, R&D capabilities and the possibility to venture with local partners. This list of host country characteristics seems well suited to our empirical case.

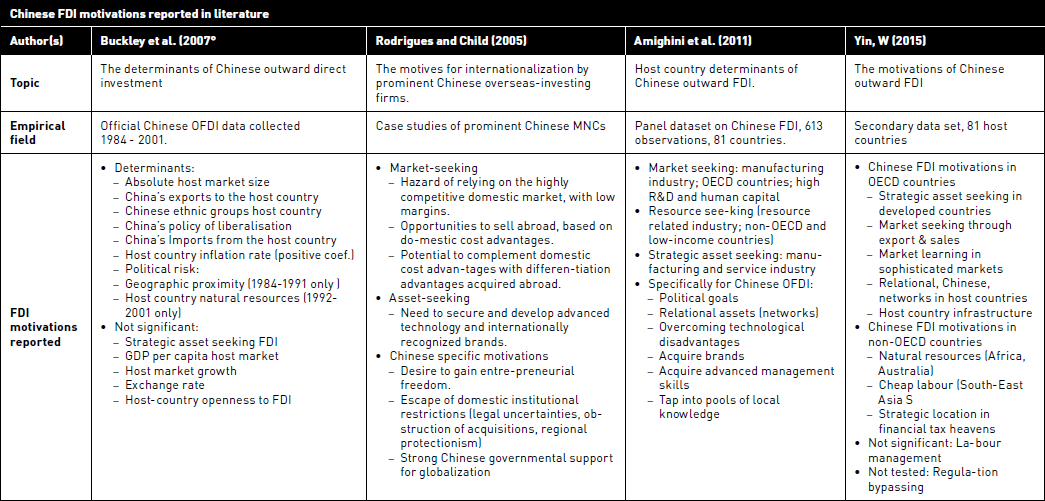

Chinese outward FDI motivation

The last decade, academic research studied more specifically the motivations and location choice of Chinese outward FDI. With official Chinese OFDI data, collected between 1984 and 2001, Buckley’s et al. (2007) find for the years 1984–1991 that Chinese OFDI is associated with high levels of political risk in host countries, large market size as well as geographic and cultural proximity. For the years 1992-2001, Chinese outward FDI is more oriented towards countries with high natural resources endowments. Kolstad and Wiig (2012), conducting a large econometric analysis with 2003–2006 data confirm that the top determinants of Chinese FDI are the market size of host countries and the presence of natural resources combined with poor local institutions.

Progressively, empirical studies with well suited primary data confirm that a growing amount of Chinese FDI is motivated by classic reasons: market-seeking FDI is looking for large and sophisticated markets, with high GDP and GDP per capita (Yin, 2015), asset-seeking FDI is attracted to developed countries where Chinese firms acquire advanced technology, internationally recognized brands and advanced management skills (Rodrigues and Child, 2005; Amighini et al., 2011; Yin, 2015), whereas resource seeking FDI is attracted to non-OECD low-income countries, where Chinese firms look for natural resources and low labour costs. Moreover, Chinese outward FDI seems to be influenced by specific Chinese determinants, such as the desire to gain entrepreneurial freedom (Rodrigues and Child, 2005; Yin, 2015), the escape of domestic institutional restrictions and uncertainties, strong Chinese governmental support in line with the Go Global policy or political objectives for especially SOE (Amighini et al., 2011). Finally, several studies report concordantly the role of relational, Chinese, networks in host countries (Buckley et al., 2007; Amighini et al., 2011; Yin, 2015).

Studying Chinese FDI in Europe, Dreger et al. (2015) confirm that market size and high technology levels in many European industries attract Chinese FDI. Minin and Zhang (2010), investigating specifically Chinese R&D units in Europe, confirm that Chinese companies have comparatively weak innovation capabilities, so they tap into European knowledge networks that enable them to explore new technological advantages and augment their home-based knowledge.

Chinese outward FDI characteristics

Deng’s (2013) meta-analysis of research about Chinese FDI (138 articles, published in 41 journals between 2001 and 2012) offers a useful starting point for describing the key characteristics of Chinese firms investing abroad. First, Chinese FDI aims to overcome latecomer disadvantages by acquiring critical assets from MNCs in mature countries. This strategic asset-seeking FDI is orchestrated mostly by large, state-controlled enterprises. Second, to meet national development priorities, Chinese companies acquire firms abroad while benefiting from government support. China’s huge foreign exchange reserves which facilitate the “Go Global” strategy. Third, Chinese FDI responds to institutional constraints, especially domestic market failures, weak intellectual property rights, and inefficient legal frameworks that discourage Chinese firms from pursuing R&D in China. Fourth, the institutional and social environment of China, characterized by centralized state-controlled firms, an authoritarian culture, and relation-based management, is very different from Western ones, so Chinese MNCs face a strong liability of foreignness when investing abroad and need to catch up when it comes to international management experience.

More recently, Ramamurti and Hillemann (2017) asking “What is Chinese about Chinese multinationals?”, observe that: (i) most Chinese MNEs are more infant than mature MNEs; (ii) the global context for internationalization helped Chinese MNEs to internationalize faster than was possible in earlier decades; (iii) Chinese MNEs benefit from government-created advantages, and (iv) leapfrogging late-mover Chinese firms gain competitive advantages in both heavy and sunrise industries.

Rui and Yip’s (2008) qualitative study ranks Chinese FDI firms in several categories, of which large state-owned enterprises acquiring natural resources, large state-owned enterprises being impelled by the “Go Global” policy, share-issuing companies serving their shareholder interests, and small private companies with entrepreneurial ambitions. We retrieve this classification with our qualitative research on Chinese FDI in France.

Although Chinese investments in Europe have increased recently, their absolute value is still rather small. China accounted for less than 1% of total FDI in the EU at the end of 2010 (Clegg and Voss, 2011). But as Zhang et al.’s (2013) statistics show, Europe is the most rapidly growing destination for Chinese investment, 60% of which goes to West Europe. Hanemann and Huotari (2016) confirm that Europe has emerged as a main destination for Chinese FDI, in line with a broader shift of Chinese investment from developing and emerging to high-income economies.

Zhang et al. (2013) specify a series of characteristics of Chinese investments in Europe. First, most Chinese acquisitions in Europe are done by private investors, not by state-owned enterprises. These private companies tend to be small, with 22 employees on average, and young (i.e., less than 9 years). Second, the preferred European countries for Chinese FDI are France, the United Kingdom, and Germany. Third, the preferred entry mode is mergers and acquisitions (M&As), whether as wholly owned subsidiaries or majority-owned joint ventures.

The current study addresses Chinese FDI in France specifically for several reasons. France’s gross domestic product (GDP) is second in Europe (after Germany), and its GDP per capita is around 37 000 U$, i.e. a total GDP of 2 488 billion de dollars, which makes it the 6th economy worldwide. With its 65 million inhabitants, France is the second largest mature consumer market in Europe, with strong competitive advantages in many sectors, including aviation, nuclear power, chemical industries, medicine, and agriculture. Its strong mathematics, physics, and engineering cultures lead to excellent research output and innovation centers, both public and private. According to global statistics (WIPO, 2017), France ranks sixth worldwide in terms of international patents. Furthermore, it receives the second most FDI from China among all European nations (AFII, 2015), attracting 16% of Chinese investment projects in Europe (the United Kingdom received 22%). More than 600 companies from China and Hong Kong operate in France, employing around 45,000 people. The total Chinese FDI stock in France is 2.8 billion euro, and in 2015, 44 new investments were recorded.

Luo and Zhang’s (2016) remind that quantitative regression is still a popular method of studying emerging market MNEs. However, “considering the potential misuse of statistical modelling and the rise of emerging market MNEs, [they] believe that more qualitative research such as fieldwork and case study can bring more insightful observations about the international process and strategic behavior of EM MNEs”. In addition, Ramamurti and Hillemann’s (2017) remind that there is great need for research on Chinese MNEs: “we need more thick descriptions and grounded research of Chinese MNEs” (op. cit., p. 17).

There is a dearth of empirical contributions on the detailed motivation of Chinese companies to invest in France and the management practices they adopt after M&As in France, matching their FDI motives. Our research attempts to fill these two complementary research gaps.

Qualitative Research Methodology

Although several recent publications contribute to a better understanding of the motives for Chinese FDI motivations, both in general (Rui and Yip, 2008; Amighini et al., 2011; Kolstad and Wiig, 2012; Peng, 2012; Deng, 2013; Yin, 2015; Luo and Zhang, 2016) and in Europe specifically (Clegg and Voss, 2011; Zhang et al., 2013; Dreger at al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2016), no studies consider Chinese FDI motivations in France explicitly or address the management styles that Chinese companies adopt to match their FDI motives. Therefore, we rely on qualitative interviews. Our empirical study uses qualitative, semi-structured interviews with managers of Chinese subsidiaries in France to clarify the reasons that drive Chinese firms to invest in France and to explore the management style that the Chinese companies adopt after an M&A in France.

Sample

We initially contacted nearly 200 managers of Chinese subsidiaries in France. However, the hierarchical Chinese corporate culture generally leads Chinese expatriates to avoid interviews. Furthermore, the expatriates who agreed to cooperate did not always meet our sample requirements. Thus, we succeeded in conducting face-to-face interviews with senior managers of 17 Chinese subsidiaries in France, including 11 Chinese expatriated and 6 local French managers. At the request of most of the interviewees, we do not give the names of the companies here, nor the interviewees’ personal identities. With this guaranteed anonymity, the respondents spoke more freely and did not feel the need to ask for permission from supervisors in the powerful Chinese corporate hierarchy. We thus indicate industries only in broad terms.

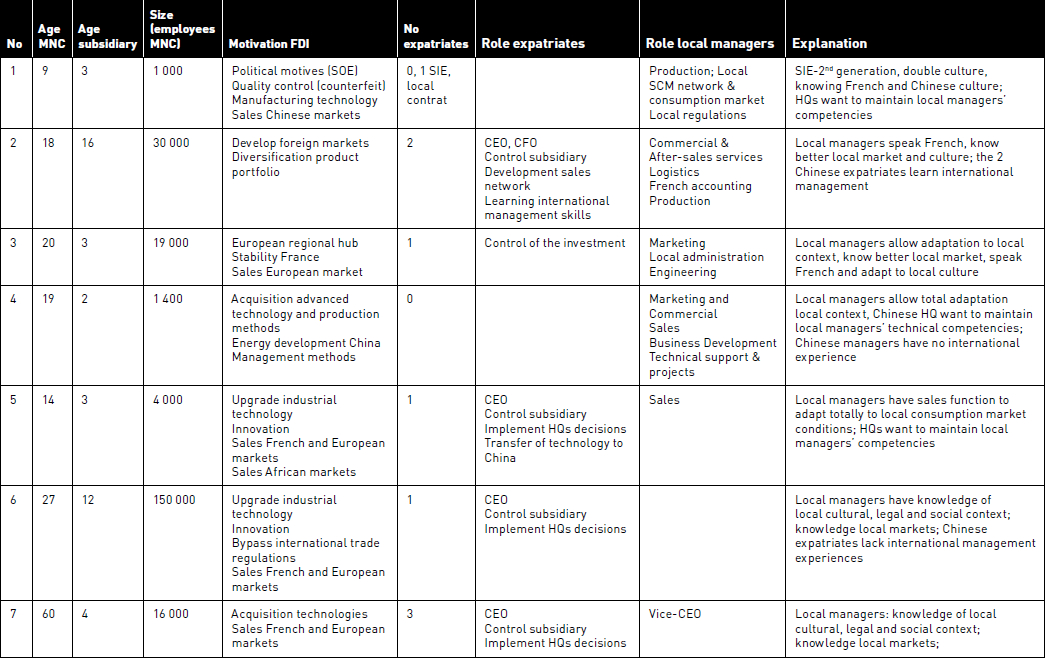

The 17 interviews led to information saturation; the last few interviews we conducted did not supply any new or significant information related to our research questions (Symon and Cassel, 1998). Table 1 gives an overview of the sample.

This sample produces three notable observations. First, two Chinese companies have less than 10 years of existence, and half are younger than 20 years. One-third of the sample is managing their subsidiary in France since less than five years, and the French entry was often their first overseas investment. In accordance with Ramamurti and Hillemann’s (2017), we might argue that the global context for internationalization helped Chinese MNEs to internationalize faster than was possible in earlier decades. Moreover, Wang et al. (2014) found evidence that “the quality of host country institutions tends to reduce the importance of prior international experience, thus attracting less-experienced latecomers, such as Chinese firms”. However, we also interviewed three Chinese companies with more than 60 years’ history and one-third of our sample had more than ten years’ experience in France.

Second, our sample contains both state-owned enterprises (9 cases, 53%) and private companies (8 cases, 47%), which invested in various industrial and service activities, including manufacturing (steel, diesel engines, tractors, consumer goods, medical equipment), transport, and services (real estate, telecommunication, broadcasting). This statistic rather confirms Hanemann and Huotari (2016), who find that 70% of Chinese FDI in Europe in 2015 is done by state-owned enterprises. Slightly more than half of the sample (9 cases) invested in manufacturing activities (consumer goods, heavy industry, machinery and engines, medical equipment).

Third, most of the companies of our sample use wholly owned subsidiaries to enter France (15 of 18[2] cases), 8 through greenfield investments and 7 through M&As. Only three Chinese companies opted for international joint ventures. These sample characteristics are consistent with Zhang et al.’s (2013) findings about the preferred entry modes for Chinese FDI and with Ramamurti and Hillemann’s (2017) conclusion that Chinese MNEs seem to have used high-commitment modes of entry, such as M&As, earlier than one would have expected.

Interviews

To prepare for the interviews, we wrote a semi-structured interview guide in French and Chinese. The interview guide started with questions about the history of the MNC in its home country. With two open-ended questions, we encouraged managers to describe their main motivations for investing in France and the entry mode their firm used. We purposefully asked about a variety of motivations; by pushing respondents to engage in deeper reasoning, we pursued an inductive posture, which is particularly useful for understanding and contextualizing FDI motivations (Silverman, 2005). In the second part of the interviews, we focused on management of the subsidiary in France, asking the respondents to describe their expatriation and localization policies, including the number of expatriates and local managers, their roles and management positions, the level of centralized decision-making as well as the use of formal and informal control mechanisms. Again, we asked the respondents to explain in greater depth, when relevant, the reasons for their management practices and to consider the cultural differences between Chinese and French managers.

Table 1

Sample characteristics

Notes: SOE = state-owned enterprise, M&A = merger and acquisitions, WOS = wholly owned subsidiary, IJV = international joint venture. For the IJVs, the first percentage listed refers to the amount held by the Chinese partner, and the second percentage is the amount held by the French partner

a : Chinese enterprise (CE) 10 conducted two acquisitions, in 2006 and 2007.

The interviews lasted between 45 minutes and 2.5 hours, sometimes including a visit to the company. We did not record the interviews, because doing so with the Chinese subordinate expatriates would have required permission from the corporate hierarchy, which is difficult to get within the Chinese corporate culture. Rather, we took careful, handwritten notes during the interviews, and then immediately thereafter, we transcribed the contents of the interviews fully. We sent the written transcription to the interviewees and asked for their feedback and validation.

Data analysis

The data analysis followed the methodology recommended by Silverman (2005) and Miles and Huberman (1994), including full transcription of the interviews, development of a coding frame that fits the theoretical background, a pilot test, revision of the codes, assessment of the reliability of the codes, and coding. We first assigned the full transcripts of the 17 interviews to a thematic content analysis grid, with one row per subsidiary and one column per question in the interview guide or per significant topic spontaneously mentioned by the respondents. Then, on the basis of our research questions and expectations, as well as extant empirical research, we drafted an initial list of codes related to Chinese FDI motivations and managerial styles in France; these codes included keywords, short sentences, and chunks of text (Miles and Huberman, 1994). A vertical reading of each question or item in the full content analysis grid helped us reduce the interviews according to these initial codes, subsidiary by subsidiary, cell by cell, to keywords, short phrases, or numbers. This analysis revealed some supplemental regularity associated with our research questions, so we added a small set of emerging codes to the initial list (Miles and Huberman, 1994). To check the reliability of our coding (Miles and Huberman, 1994), each member of the research team performed individual coding. Any differences were resolved through discussion[3]. To understand the FDI motivations and managerial choices made by the interviewed Chinese companies, we looked for similarities and contrasts related to each dimension. Finally, through repeated readings of the interviews, we identified brief examples to help illustrate our findings.

Empirical Results

We present our findings related the main motivations for China’s FDI in France first, followed by the results detailing the management styles that the Chinese firms adopt.

Main motivations for Chinese FDI in France

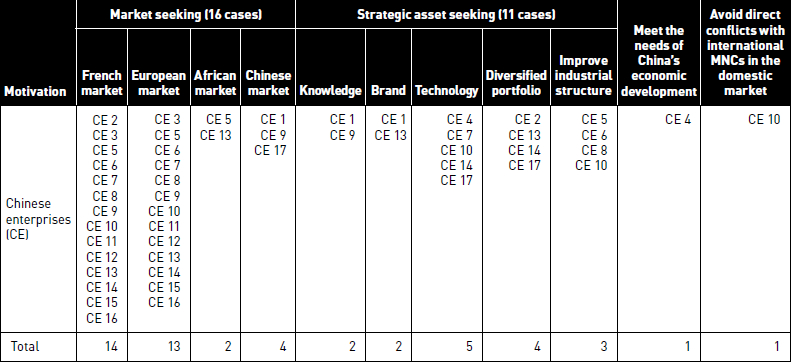

Table 2 arranges the FDI motivations of the Chinese firms of our sample into three main categories: market-seeking, strategic asset–seeking, and “other” motivations.

Market seeking

Table 2 shows clearly that the most important reasons for Chinese investments in France are market seeking (16 of 17 cases), in line with both Kolstad and Wiig’s (2012) findings that Chinese outward FDI is attracted to large markets and Dreger et al.’s (2015) claim that market size is the primary reason driving Chinese FDI in the EU. For four Chinese firms, in the maritime transport (CE 2), chemical (CE 10), medical equipment (CE 12), and diesel manufacturing (CE 13) sectors, accessing the French market is their main goal, sometimes in combination with a search for strategic assets (CE 10, CE 13). France is a vast consumer market, with a high degree of openness and large export possibilities for Chinese products. With its location in the western part of the European Union and well-developed transport system (railways, tunnel to the United Kingdom, roads, harbors at both Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts), France offers a perfect hub, connecting Chinese investors to the other large EU consumer markets, such as Germany, the UK, Italy, Spain, and the Benelux. Many respondents thus note that France possesses localization advantages that no other European country has, and three-quarters of our sample (13 cases) acknowledge that their French FDI represents a gateway to the broader European market.

Table 2

FDI motivations of the Chinese firms of our sample

Two firms of our sample also invest in France with an eye to African markets. Many West and North African countries are former French colonies, with persistent cultural, political, and economic links to France. In total, around 20 countries in Africa have French as a common language, spanning a total population of around 400 million people. Furthermore, for many of these countries, France is a primary trade partner and the principal access to the European markets. As CE 5 and 13 explained, their France subsidiary thus helps them build a bridge to French-speaking African markets, by setting up sales and transport networks to Africa. For CE 5, a wig manufacturer, Africa is a critical market; it also represents a very appealing market for the diesel engines produced in France by CE 13.

Rui and Yip (2008) also note remind that some domestically oriented Chinese firm acquire firms abroad with the strategic intent to compete with foreign MNCs in the Chinese market while benefitting from the acquired strategic assets abroad. For many Chinese firms, winning the domestic market remains very important, including CEs 1, 9, 10, and 17 in our sample. For CEs 1 and 9, which operate in consumer goods industries, meeting the needs of the immense Chinese consumer market remains a primary strategic goal. They acquired French companies to integrate those companies’ brands (CE 1) and production knowledge (CE 1 and 9). In the mining sector, the representative of CE 17 explained that the firm is less interested in developing its French or European market; it entered into a joint venture with a French company to diversify its product portfolio and upgrade its technology, which in turn should help it expand its sales in China.

Strategic asset seeking

The search for strategic resources and assets is the main motivation to invest in France for 11 Chinese firms. This strategic asset–seeking behavior can complement market-seeking behavior too. Three CEs, 5 (wigs), 6 (telecommunication), and 10 (chemicals), underlined that their manufactured products are situated at the end of their value chains, so their investments in France serve their goal of upgrading their production methods in China. Four CEs, 4 (nuclear energy), 7 (tractors), 14 (steel), and 17 (mining), acquired technological knowledge in France, according to their goals of evolving toward higher value-added products that they can offer on both Chinese and international markets. CEs 1 (consumer goods) and 9 (wolfberries) stated that they acquired knowledge in more general way, while CEs 2 (maritime transport), 13 (diesel engines), 14 (steel), and 17 (mining) have invested in France with the idea of diversifying their portfolios of products and services.

For a long time, Chinese manufacturing companies have relied on China’s demographic rents and low labor cost advantages to export Chinese products worldwide. However, production costs have risen in China, and the cost advantages are gradually weakening, so developing new competitive advantages is imperative for the firms in our sample. They cite FDI in industrialized countries as a suitable means to enhance their level of global competitiveness quickly. They also confirm their view of France as a creative, innovative country, with highly skilled engineers and managers. Many small and medium-sized technological firms in France, suffering from the enduring economic crisis, needed new capital to survive, and an M&A with a Chinese firm offered them a reasonable solution to avoid bankruptcy.

The interviewees also stated that a “Made in China” label tends not to inspire much trust among consumers. China is still considered as the world’s factory, producing low-cost products for international markets or original equipment products for international brands. Thus CE 13, which produces diesel engines, sought to enhance its sales in France and Europe by acquiring a well-known French brand. Scandals involving Chinese brands resulted in greater skepticism among Chinese consumers, who seek foreign brands with better reputations. Chinese consumers believe foreign brands offer better quality and service and regard them as safer and more durable, particularly in the food sector. Thus CE 1 acquired a well-reputed French brand to develop its sales on the Chinese market.

Other FDI motivations

Two Chinese companies offered two further FDI motivations, complementary to the market- and asset-seeking motivations: bypassing the regulatory protections of the French and European markets (CE 6) and avoiding direct confrontation in the Chinese market with global MNCs (CE 10). As a big player in the Chinese telecommunication market, CE 6 set up a wholly owned subsidiary through a greenfield investment in France, designed to circumvent political and non-tariff barriers to entering the protected and highly regulated French and European telecommunication markets.

In the chemical industry, with the strong development of the huge Chinese consumer market, many foreign MNCs have created subsidiaries in China in the past decade, raising the level of competition and challenging local Chinese firms that were not sufficiently competitive. To improve its competitiveness but avoid direct conflict with foreign MNCs in China, CE 10 engaged in dual acquisitions in France, in 2006 and 2007, with the clear goal of strengthening its technological and innovative capacity to sell products in the Chinese market. This FDI behavior corresponds to the springboard theory (Luo and Tung, 2007). As the home country market is still CE 10’s primary operations territory, it attempts to use its international expansion as a springboard to acquire critical resources and to compete more effectively against global rivals, abroad and in its home market.

Polycentric Chinese management styles

Referring to the EPRG framework (Perlmutter, 1969; Perlmutter and Heenan, 1974), we remind that ethnocentric management and staffing is a home-country oriented management, whereby the practices and policies of the Chinese headquarters are the international default standard to which subsidiaries abroad much comply. Expatriated Chinese managers are supposed to be capable to drive the international activities of the Chinese multinational and to manage subsidiaries abroad. The major advantages of ethnocentric management are good communication, coordination and control links with headquarters. However ethnocentric management does not take advantage of the talents of host-country nationals, which might lead to high turnover among local national managers and difficulty of adaptation to the host environment. At the opposite, polycentric management and staffing is a host-country oriented management. The Chinese headquarters consider that the contexts of the host countries where they set up subsidiaries are difficult to understand for Chinese expatriates. Therefore, subsidiary management is left over to local managers. The advantages associated with the use of host-country nationals include familiarity with the local culture, knowledge of language, reduced costs and low turnover of local managers. The main inconvenient of polycentric management is the difficulty of bridging the gap between subsidiaries and headquarters.

In nearly all the cases included in this study, the Chinese companies rely on local managers to staff most managerial and technical functions, whereas expatriated Chinese managers adopt an observational attitude. The differences in their approaches pertain mainly to the level of implementation. A series of complementary reasons underlie this polycentric approach. First, market-seeking Chinese companies, looking to develop their French and European markets (16 cases), clearly admit that they lack knowledge of these markets. To address the needs of French and European consumers, hiring experienced French and European managers to perform marketing and product innovation tasks appears compulsory.

Second, asset-seeking Chinese companies explain that they aim at transferring the acquired technologies and production methods to their factories in China. The ultimate goal is to improve the quality of their Chinese domestic production and to evolve to higher value added products. To reach this goal, the Chinese HQs need to maintain and integrate the knowledge of the local, French, engineers and technicians.

Third, France and China have very different cultures and traditions. Chinese managers do not always understand French culture or its legal, social, and institutional frameworks, which hinders the economic development of the Chinese firms in France. To avoid cross-cultural mismanagement or mistakes, the Chinese firms thus hire local managers to ensure effective post-acquisition integration. Most of our interviewees noted that their parent companies lack the international experience needed to manage a global company.

The fourth reason is relatively context bounded. France is a welfare state with strongly developed social and legal measures to protect employees’ interests. Trade unions are very active in some sectors, firing procedures are complicated and uncertain. The consistently high unemployment rates and political sensitivity to Chinese investments also prompts French administrative authorities to take close looks at Chinese M&As in France. In order to avoid unnecessary social conflicts and keep the social peace, most Chinese firms that acquired a French firm retained the employees of the French firm after the acquisition.

Discussion

We would like to remind the background of our research. Although academic research on the motivations of Chinese outward FDI has been abundant the last ten years (Luo and Zhang, 2016), there is still a research gap on the deeper motivations of Chinese firms to invest in advanced European economies (Ramamurti and Hillemann, 2017). Our research aims to fill in this gap. In addition, related to their FDI motivations, our research investigates the management style and practices that the Chinese firms adopt after acquiring a subsidiary in France. Only a very few academic empirical researches (Shen and Edwards, 2006; Fan et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014) have explored this question.

We interviewed 17 expatriate and local managers of Chinese subsidiaries in France to learn the main motivations that led their Chinese parent company to set up a subsidiary in France, as well as the management style that the Chinese companies adopted. The interview results reveal that these Chinese companies pursue two main goals with their FDI in France. The first motive (16 of 17 cases) is market seeking. Chinese companies want to increase their sales in French and European Union markets. Two Chinese companies also are looking at the francophone West African markets, with which France has historical connections. Another Chinese company targets to enter the highly protected European telecommunication market by establishing a subsidiary in France, while a direct access for Chinese companies is complicated.

The second FDI motive is strategic asset seeking (11 of 17 cases), which might be linked to market-seeking motivations. The Chinese firms of our sample acquire non-exclusive and complementary categories of strategic assets, with the aim to enhance their global competitiveness in international markets and their domestic market. As such, we confirm Zheng et al’s. (2016) findings that Chinese MNEs, investing in developed economies, seek strategic assets, in similar domains but at a more advanced level, which are complementary to the firm-specific assets they already possess, with the goal to enhance their competitive advantages at home. We find that the strategic assets the Chinese firms acquire through their FDI in France include industry-related technology, advanced production methods to upgrade their industrial capacity, R&D and innovation capabilities to develop higher added-value products and services as well as international recognized brands. This list of assets confirms the strategic assets Chinese firms acquire in Germany, Italy and the UK (Zheng et al., 2016). Moreover, we find that the Chinese companies of our sample are looking in France for managerial skills to help address the lack of international experience of their Chinese managers.

Luo and Zhang (2016, p. 345) in their review of 166 articles from 11 leading international business journals indicate among the future research directions: “Do emerging markets MNEs suffer liability of emergingness? If yes, how do they cope with?”. Moreover, they ask: “How do they [emerging markets MNEs] achieve accelerated learning while avoiding traps and management failure?” (op. cit., p. 347). Some recent academic empirical researches bring elements that allow to answer these questions. For instance, interviewing 16 top executives of three Chinese subsidiaries established in Australia, Fan et al. (2013, p. 537), stating that “China lacks personnel who possess international management skills, sufficient knowledge about market conditions of host countries and a good understanding of the intricacies of international business”, show that the Chinese MNEs of their sample “empowered local managers, decentralized managerial roles and offered Australian managers flexibility to the greatest extent” (op. cit., p. 533). Wang et al. (2014), based on survey data collected from senior executives of 240 Chinese MNEs, find that Chinese headquarters grant management autonomy to their foreign subsidiaries, especially when they have to acquire strategic assets on foreign markets perceived with high domestic constraints. They conclude that “subsidiary autonomy is a strategic mechanism to overcome the Chinese weaknesses in managing globally dispersed businesses and their home-country disadvantages after a foreign entry. More precisely in Germany, Italy and the UK, Zheng et al. (2016, p. 184), confirming that “Chinese multinationals still lack the resources and capabilities in managing target firms with different national and organisational cultures in a different institutional context”, find that “the Chinese parent companies maintain the original organisational structure of target firms and grant autonomy to target firm managers”.

More specifically about Chinese expatriation, Zhong et al’s (2015) literature review of 163 academic articles on expatriation in the context of China, published between 2001 and 2013, shows that research has been dominated by issues on foreign expatriates working in China, not Chinese expatriates working overseas. Of these 163 articles, 84 are in English and 79 in Chinese[4]. Of the 84 articles in English, only 8[5] focused on mainland Chinese expatriates working abroad. Consequently, little is known about Chinese expatriation. In a conceptual paper, Jackson and Horwitz (2017) suggest that Chinese multinationals rely on expatriates for the management of their subsidiaries in Africa, although they might be “ill-equipped to interact with locals at work and in the community with a detrimental effect on mutual learning” (op. cit., p. 11). However, we might suppose that natural resources seeking motives determine differently international HRM policies. Shen and Edwards (2006), doing case studies of 10 Chinese multinationals, find that five companies of their sample adopted an ethnocentric international HRM approach by making great use of parent-country nationals rather than recruiting host-country nationals. At the opposite, two firms clearly adopted a polycentric international HRM, employing a large number of host-country managers and granting subsidiaries operational freedom. The three remaining firms of their sample adopted an ethnocentric staffing policy with a polycentric tendency, employing more host-country nationals in middle management positions and localizing some HRM activities. The authors’ analyses suggest that large or middle-sized state-owned multinationals with rather large-scale international activities adopt rather ethnocentric management for their foreign subsidiaries. Polycentric firms, or with a polycentric tendency, are more often at an early stage of internationalization, with a rather small size of international operations, which lack international management experiences. One firm of their sample, localizing downstream activities, where marketing, branding, sales and service are important to achieve a competitive advantage, states that it is “difficult to explore local markets due to a lack of localization of employment” (op. cit., p.123).

In line with these studies (Shen and Edwards, 2006; Fan et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2016), we find that Chinese companies adopt a polycentric management style, relying on local, French and European, managers and engineers to manage their French subsidiary, while Chinese expatriate managers undergo learning processes. The Chinese firms of our sample adopt in their French subsidiaries such a polycentric management style for several reasons. First, market-seeking Chinese companies need to get access to the knowledge of the French and European markets of their local, French, managers. Second, asset-seeking Chinese companies need to maintain French engineers and technicians and integrate their technological knowledge in the value chain of the Chinese multinational. Third, the Chinese firms, who are sometimes rather young and undergoing a quick internationalization process, lack international experience. Fourth, as the Chinese and French national and corporate cultures are very different, the Chinese companies want to avoid cross-cultural mistakes that might hinder the development of the French subsidiary or its knowledge absorption. Moreover, some Chinese companies of our sample want to keep social peace and avoid violating France’s strict legal and social employment regulations and protections. We can see clearly that the polycentric management that Chinese firms in France adopt relates to market and asset-seeking FDI motives.

Miles and Huberman (1994, p. 75) suggest that: “As a study proceeds, there is a greater need to formalize and systemize the researchers’ thinking into a coherent set of explanations; one way to do so is to generate propositions, or connected sets of statements, reflecting the findings and conclusions of the study”. In line with these recommendations, our empirical study leads to the following research propositions:

Proposition 1: When Chinese outward FDI is done in advanced economies, with market-seeking goals, in order to maintain knowledge on local consumption markets, the Chinese multinational mother company adopts polycentric management practices and staffing.

Proposition 2: When Chinese outward FDI is done in advanced economies, with asset-seeking goals, in order to integrate knowledge and technology in the MNC’s value chain, the Chinese multinational mother company adopts polycentric management practices and staffing.

Proposition 3: When Chinese outward FDI is done by young Chinese companies, without significant international experience, the Chinese multinational mother company adopts polycentric management practices and staffing.

Our research contributes to FDI theory in several ways. First, we find that Chinese FDI in developed countries has both market-seeking and strategic asset–seeking goals. Second, we confirm the linkage, leverage, and learning perspective of reverse FDI (Mathews 2002, 2006). Many Chinese companies are in the process of connecting with innovative French firms to learn how to improve their own global competitiveness, through industrial upgrades, enhanced R&D capabilities, or portfolio diversification. Third, one case in our study fits the springboard theory (Luo and Tung 2007): it invested in France to acquire and integrate strategic resources and thereby compete better with foreign MNCs in its domestic Chinese market. Fourth, many Chinese firms, both private and state-owned, receive direct (subsidies) or indirect (low-interest rates, loans, tax advantages) support from Chinese authorities, confirming the involvement of the Chinese government in Chinese FDI and leading to “government-created advantages” (Ramamurti and Hillemann, 2017), which enhance FDI of Chinese firms with relatively few prior international experience. Fifth, our research offers a new theoretical lens to look at Chinese FDI in Europe, we call the “bridging theory”. Some Chinese firms acquired French firms with the aim of building bridges to West-African markets, which have strong historical ties with France. Thanks to the distribution networks and knowledge about African markets of the French subsidiaries, Chinese multinationals seek to enhance their sales on those French-speaking African markets.

Conclusion

To explore the main motivations for Chinese direct investments in France, as well as the management styles that Chinese companies adopt to manage their subsidiaries in France, we conducted semi-structured interviews with Chinese expatriate and French managers of 17 Chinese subsidiaries in France. The main goal for Chinese FDI in France is market seeking. Chinese parent companies seek to enhance their sales in French and European markets, as well as in francophone African markets, through their subsidiary in France. In addition, Chinese companies invest in France to acquire strategic assets, of which especially innovative technologies, R&D capabilities, advanced production techniques, and international brands.

Because Chinese companies lack international managerial experience, they tend to adopt polycentric management approaches toward their subsidiaries in France, whether they have entered into international joint ventures or set up wholly owned subsidiaries. Chinese expatriate managers and engineers undergo learning processes, such that they observe how the local French or European employees perform key management and technical roles.

Academic literature on Chinese outward FDI to industrialized countries and the resulting management styles for their subsidiaries is scarce. Therefore, we intentionally adopted an inductive posture and undertook qualitative research for this study. With semi-structured interviews, we obtained in-depth insights into the underlying reasons that led Chinese companies to invest in France and choose specific management policies for their subsidiaries. However, the shortcomings of qualitative interviews are well known. Generalization of our research findings requires caution.

For further research, our conclusions suggest two directions. First, what management style and practices Chinese firms adopt when investing in advanced European economies such as the UK or Germany? Also, are Chinese management style and practices different when their FDI is resource-seeking, in Africa or Australia for instance, or takes place in geographically and culturally close countries in South-East Asia? Second, further research could deepen the bridging perspective of FDI. Especially, does Chinese FDI in the UK look for bridges to former countries of the British Empire?

Parties annexes

Appendices

Appendix 1. Table of FDI motivations reported in literature

Appendix 2. Reduced content grid

Biographical notes

Ni Gao is Assistant Professor at Kedge Business School in Bordeaux. She holds a PhD in Management from the University of Pau and the Pays de l’Adour. Here academic research focuses on emerging countries’ direct investments in Europe. More specifically, Ni Gao studies the internationalization strategies of Chinese companies as well as the specificities of Chinese international management, including Chinese expatriation and the way that Chinese companies exercise control over their subsidiaries in Europe.

Johannes Schaaper is Associate Professor at the Institute of Business Administration of the University of Bordeaux (IAE Bordeaux) and member of the research laboratory IRGO of the University of Bordeaux. He holds a PhD in Economics and a Research Accreditation in Management Science. His research interests are in the field of international management, with a special focus on Asian markets. He has published in numerous academic journals, in French and English. His has professional experiences in varied countries such as The Netherlands, France, Lebanon, China, and Japan, which enriches his perception of international management issues.

Notes

-

[1]

Appendix 1 gives a short overview of the main FDI motivations reported in literature, with a focus on Chinese outward FDI motivations.

-

[2]

Because CE 10 invested twice.

-

[3]

The reduced content grid, with key words, numbers, short sentences and chunks of text is reproduced in appendix 2.

-

[4]

Implicitly the author, although obviously reading Chinese, does not consider the 79 articles in Chinese for his literature review. This poses the question of the language of academic research.

-

[5]

Zhong et al. (2015) say 12 articles; however 4 articles deal with expatriates from Taiwan; therefore, we state that only 8 articles focus on mainland Chinese expatriates.

Bibliography

- AFII (2015). “The International Development of the French Economy”, AFII Annual Report. Foreign Investment in France, Invest in France Agency, Paris.

- Amighini, A.; Rabellotti, R.; Sanfilippo, M. (2011). “China’s outward FDI: An industry-level analysis of host country determinants”, CESifo working paper, Empirical and Theoretical Methods, No. 3688, Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute, Munich.

- Buckley, P.J.; Clegg, L.J.; Cross, A.R.; Lin, X.; Voss, H.; Zheng, P. (2007). “The determinants of Chinese outward FDI”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 38, N° 4, p. 499-518.

- Child, J.; Rodrigues, S.B. (2005). “The internationalization of Chinese firms: A case for theoretical extension?”, Management and Organization Review, Vol. 1, N° 3, p. 381-410.

- Clegg, J.; Voss, H. (2011). “Inside the China–EU FDI bond”, China & World Economy, Vol. 19, N° 4, p. 92-108.

- Deng, P. (2013). “Chinese outward direct investment research: Theoretical integration and recommendations”, Management and Organization Review, Vol. 9, N° 3, p. 513–539

- Dreger, C.; Schüler-Zhou, Y.; Schüller, M. (2015). “Determinants of Chinese direct investments in the European Union”, Discussion Paper, N° 1480, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung.

- Driffield, N.; Love, J.H. (2007). “Linking FDI motivation and host economy productivity effects: conceptual and empirical analysis”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 38, p. 460-473.

- Dunning, J.; Lundan, S.M. (2008), Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy, 2nd ed., Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK, Northampton, MA, USA

- Fan, D.; Zhang, M.M.; Zhu, C.J. (2013). “International human resource management strategies of Chinese multinationals operating abroad”, Asia Pacific Business Review, Vol. 19, N° 4, p. 526–541

- Giroud, A.; Mirza H. (2015). “Refining of FDI motivations by integrating global value chains’ considerations”, The Multinational Business Review, Vol. 23, N° 1, p. 67-76

- Hanemann, T.; Huotari, M. (2016). A new record year for Chinese outbound investment in Europe, http://www.merics.org/fileadmin/user_upload/downloads/COFDI_2016/A_New_Record_Year_for_Chinese_Outbound_Investment_in_Europe.pdf, accessed 31 December 2017.

- Jackson, T.; Horwitz, F. (2017). “Expatriation in Chinese MNEs in Africa: an agenda for research”, The International Journal of Human Resource, on-line 10.1080/09585192.2017.1284882

- Kolstad, I.; Wiig, A. (2012). “What determines Chinese outward FDI?”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 47, N° 1, p. 26–34.

- Lall, S. (1984). The New Multinationals: The Spread of Third World Enterprises, New York, Wiley, IRM Series on Multinationals.

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, H. (2016). “Emerging Market MNEs: Qualitative Review and Theoretical Directions”, Journal of International Management, Vol. 22, p. 333–350

- Luo, Y.; Tung, R.L. (2007). “International expansion of emerging market enterprises: A springboard perspective”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 38, N° 4, p. 481–498.

- Makino, S.; Lau, C.M.; Yeh, R.S. (2002). “Asset-exploitation versus asset-seeking: Implications for location choice of foreign direct investment from newly industrialized economies”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 33, N° 3, p. 403-421.

- Mathews, J. (2002). Dragon Multinational: Towards a New Model of Global Growth, New York, Oxford University Press.

- Mathews, J. (2006). “Dragon Multinationals: New Players in 21st Century globalization”, Asia-Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 23, N° 1, p.5-27.

- Miedtank., T. (2017). “International human resource management and employment relations of Chinese MNCs”, in Drahokoupil., J (Ed), Chinese investment in Europe: corporate strategies and labour relations, ETUI Printshop, Brussels

- Miles, M.; Huberman, A. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis, London, Sage.

- Minin, A.D.; Zhang, J. (2010). “An exploratory study on international R&D strategies of Chinese companies in Europe”, Review of Policy Research, Vol. 27, N° 4, p. 433-455.

- Peng, M.W. (2012). “The global strategy of emerging multinationals from China”, Global Strategy Journal, Vol. 2, p. 97–107.

- Perlmutter, H.V. (1969). “The tortuous evolution of the multinational corporation”, Columbia Journal of World Business, Vol. 4, January–February, p. 9-18.

- Perlmutter, H. V.; Heenan, D. A., (1974). “How multinational should your top managers be”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 52, N° 6, p. 121-132

- Ramamurti, R.; Hillemann, J. (2017). “What is “Chinese” about Chinese multinationals?”, Journal of International Business Studies, available on-line, www.jibs.net, to be printed in 2018

- Ren, B.; Liang, H.; Zheng, Y. (2012). “An institutional perspective and the role of the state for Chinese OFDI”, Chinese International Investments. 11-37. Research Collection, Lee Kong Chian School of Business.

- Rui, H.; Yip, G. (2008). “Foreign acquisitions by Chinese firms: A strategic intent perspective”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 43, N° 2, p. 213-26.

- Shen J.; Edwards V. (2006). International Human Resource Management in Chinese Multinationals, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group

- Silverman, D. (2005). Doing qualitative research; a practical handbook, London, Sage Publications.

- Symon, G.; Cassel, C. (1998). Qualitative Methods and Analysis in Organizational Research, Newbury Park, CA, Sage.

- Thite, M.; Wilkinson, A.; Budhwar, P.; Mathews, J.A. (2016). “Internationalization of emerging Indian multinationals: Linkage, leverage and learning (LLL) perspective”, International Business Review, Vol. 25, p. 435–443

- Wang, S.L.; Luo, Y.; Lu, X.; Sun, J.; Maksimov, V. (2014). “Autonomy delegation to foreign subsidiaries: An enabling mechanism for emerging-market multinationals”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 45, N° 2, p. 111-130

- WIPO (2017). “World Intellectual Property Indicators”, Economics & Statistics Series. World Intellectual Property Organization, yearly report 2016.

- UNCTAD (2017). World Investment Report 2017, United Nations Publication, Geneva

- Yin, W. (2015). “Motivations of Chinese outward foreign direct investment: an organizing framework and empirical investigation”, Journal of International Business and Economy, Vol. 16, N° 1, p. 82-106

- Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; VanDenBulcke, D. (2013). “Euro-China Investment report 2013-2014. Chinese owned enterprises in Europe: a study of corporate and entrepreneurial firms and the role of sister city relationships”, Euro-China Centre at the Antwerp Management School, Antwerp

- Zheng, N.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J. (2016). “In search of strategic assets through cross-border merger and acquisitions: Evidence from Chinese multinational enterprises in developed economies”, International Business Review, Vol. 25, p. 177–186

- Zhong, Y., Zhu, C.J., Zhang, M.M., (2015). “The management of Chinese MNEs’ expatriates”, Journal of Global Mobility, Vol. 3 N° 3, p. 289-302

Parties annexes

Notes biographiques

Ni Gao est Professeur Assistant à Kedge Business School à Bordeaux. Elle est titulaire d’un Doctorat en Sciences de Gestion de l’Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour. Ses recherches universitaires portent sur les investissements directs des pays émergents en Europe. Plus spécifiquement, Ni GAO étudie les stratégies d’internationalisation des entreprises chinoises ainsi que les spécificités du management international chinois, notamment l’expatriation chinoise et la manière dont les entreprises chinoises exercent un contrôle sur leurs filiales en Europe.

Johannes Schaaper est Maître de Conférences HDR à l’IAE de l’Université de Bordeaux et membre du laboratoire de recherche IRGO. Ses travaux sont dans le domaine du management international, à la fois dans la perspective stratégique et organisationnelle et du point de vue du marketing, avec une spécialisation sur les marches asiatiques. Il a publié dans de nombreuses revues académiques, en français et en anglais. Son expérience professionnelle dans divers pays comme la France, les Pays-Bas, le Liban, la Chine et le Japon enrichissent son approche des questions de management international.

Parties annexes

Notas biograficas

Ni Gao es Profesor Adjunto en la Kedge Business School de Bordeaux. Es doctora en Gestión por la Universidad de Pau y el Pays de l’Adour. Su investigación académica se centra en las inversiones directas de los países emergentes en Europa. Más específicamente, Ni Gao estudia las estrategias de internacionalización de las empresas chinas, así como las especificidades de la gestión internacional china, incluyendo la expatriación china y la forma en que las empresas chinas ejercen el control sobre sus filiales en Europa.

Johannes Schaaper es Profesor Asociado del Instituto de Administración de Empresas de la Universidad de Bordeaux (IAE Bordeaux) y miembro del laboratorio de investigación IRGO de la Universidad de Bordeaux. Su trabajo se desarrolla en el campo de la gestión internacional, tanto desde una perspectiva estratégica y organizativa como desde el punto de vista del marketing, con especialización en los mercados asiáticos. Ha publicado en numerosas revistas académicas, en francés e inglés. Su experiencia profesional en varios países como Francia, Holanda, Líbano, China y Japón enriquece su enfoque de la gestión internacional.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Sample characteristics

Notes: SOE = state-owned enterprise, M&A = merger and acquisitions, WOS = wholly owned subsidiary, IJV = international joint venture. For the IJVs, the first percentage listed refers to the amount held by the Chinese partner, and the second percentage is the amount held by the French partner

a : Chinese enterprise (CE) 10 conducted two acquisitions, in 2006 and 2007.

Table 2

FDI motivations of the Chinese firms of our sample